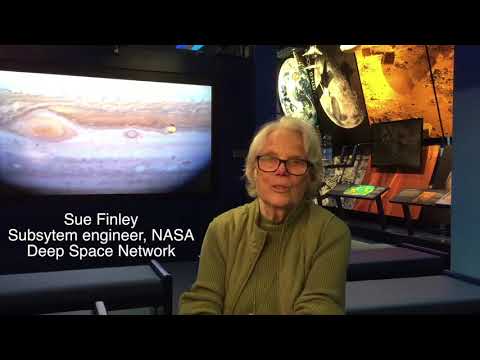

How I Made It: Hired in 1958 as a ‘computer,’ Sue Finley talks about her long career at JPL

Sue Finley, one of the longest-serving employees at NASA, got her start as a “computer” at JPL.

Sue Finley, 80, has worked at

A knack for numbers

Finley was born in downtown Los Angeles and later moved with her family to Fresno at age 6. She came back to Southern California to attend Scripps College in Claremont and intended to learn art. But Finley left school before her last year after realizing that “you can’t learn art” and that she wouldn’t be able to do a senior thesis on the subject.

She decided that she couldn’t waste her mother’s money, and instead scanned newspaper ads for jobs. Finley eventually came across an opening for a file clerk at aircraft maker Convair in Pomona. She applied, took a typing test and was told the next day that the position had already been filled. But Finley was asked if she liked numbers.

“I said, ‘Oh, I love numbers, much better than letters,’ ” she said. “So they put me to work as a computer.”

Closer commute

Finley used a Frieden calculator — a typewriter-sized electronic machine — to solve equations for the engineers in Convair’s thermodynamics section for about a year. She got married in 1957 and moved to San Gabriel.

During one particularly foggy commute to Pomona, she decided that it would be better to get a job closer to home. Her husband, a recent

JPL needed a computer, and Finley was hired. Three days later, the U.S. space program took a giant leap forward by launching its first satellite, Explorer 1, which was designed, built and operated by JPL.

“What I remember was this great big sheet cake that we all got,” Finley said. “And there weren’t that many people working at JPL [at the time] that they could use just one sheet cake.”

Programming experience

Finley worked at JPL for 2½ years until she and her husband moved to Riverside so he could attend graduate school at the UC. Jobs were scarce during the recession of 1960 to 1961, so a posting on a college bulletin board caught her eye: a free weeklong class in Fortran programming.

After her husband finished his master’s program, they moved to Pasadena and Finley returned to JPL in 1962, armed with her new knowledge. She was one of just a few people at the lab who knew Fortran. Today, one of the programs that Finley wrote to help navigate spacecraft is still being used at JPL, though with a bit of an upgrade.

Oh, I love numbers, much better than letters.

— Sue Finley

Camaraderie at JPL

Finley left JPL once more in 1963 to take care of her two sons, but returned six years later for good. By her third turn, there were more women at the lab and the human computers had largely transitioned into roles as computer programmers. The women forged close ties, and Finley said they were all “very good friends, and still are.”

By the 1970s, the women who were computers had left their separate all-female office and were integrated into various mission teams.

“The men always, from the very beginning, treated us as equals,” Finley said. “We were doing something they couldn’t do and that they needed to go forward with what they were doing.”

Most memorable mission

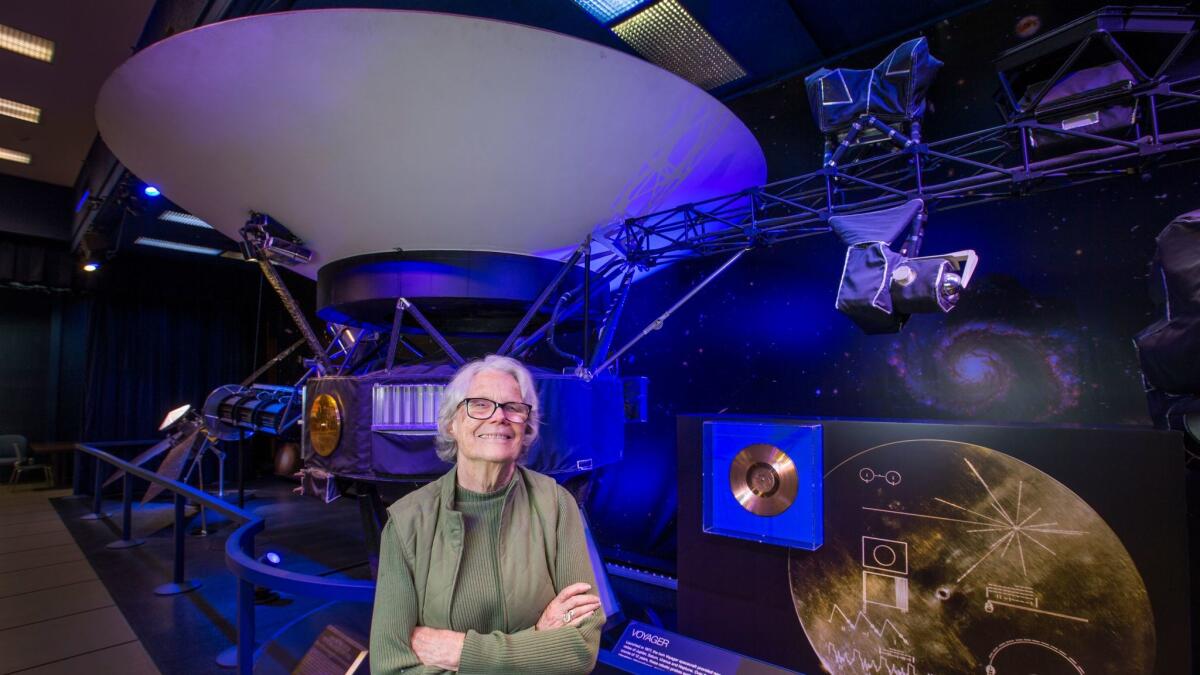

In 1980, Finley began working on NASA’s Deep Space Network — a system of giant radio antennas around the world that connects with spacecraft on interplanetary missions, as well as some spacecraft that orbit Earth.

One of those missions was the Venus Balloon Project, during which two Russian space probes, on their way to Halley’s Comet, deployed two balloons into Venus’ atmosphere in 1985 to collect data about the environment. Although the project was a joint Soviet-French mission, the JPL-operated DSN, as it’s known, was tracking the spacecraft.

Finley was responsible for writing a program that automated movement commands for a DSN antenna. The antenna needed to be pointed exactly at the spacecraft to receive any data from it.

“I can remember when we saw the first signal in the darkroom, I actually jumped up and down because I was so happy,” Finley said.

Tuning up

Finley helped design the tones — special sets of radio frequencies emitted by a spacecraft that correspond with actions taken, such as a valve opening — for the Juno mission, which entered Jupiter’s orbit last year. NASA relied on the tones to get real-time status updates on Juno when the spacecraft was pointed away from the Earth and could not send regular telemetry because the signal was too weak.

“That was really fun,” Finley said.

Current work

Today Finley is helping to design and test a new, pizza box-sized receiver for the DSN. She is also working on a concept that would allow small satellites to transmit data by intercepting the beam of a larger spacecraft’s antenna.

She has no plans to retire. “I love coming to work,” Finley said. “You learn something new every day.”

Personal

Finley lives in Arcadia and likes going to the symphony, the ballet and seeing plays at the theater. She also enjoys traveling and visiting her four grandchildren, who live in St. Louis and Andover, Mass.

Twitter: @smasunaga

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.