How I Made It: A restaurant customer helped launch Chris Hernandez’s aerospace career

Chris Hernandez, 59, is sector vice president of research, technology and engineering at

Making an impression

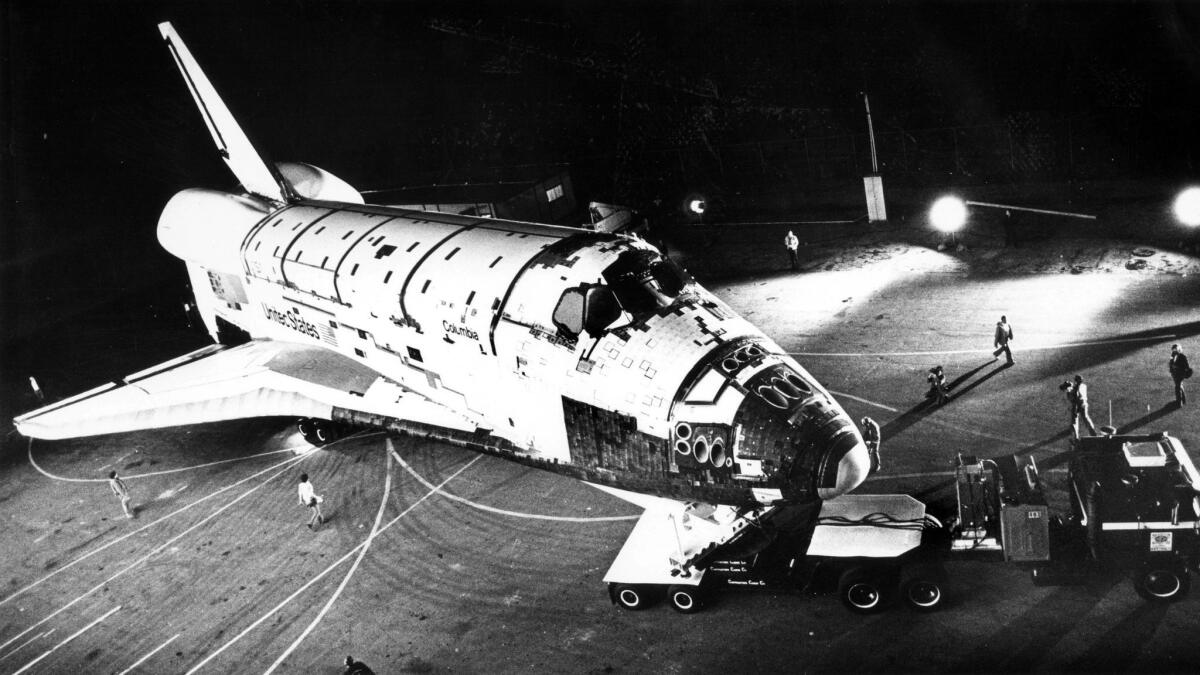

As a teenager growing up in Norwalk, Hernandez worked as a busboy in a Lakewood prime rib dinner house. One of his regular customers was Ed Smith, the space shuttle program manager for North American Rockwell, later Rockwell International Corp. The two bonded over their mutual love of flying airplanes — a skill Hernandez was learning in exchange for washing planes on weekends at a small Huntington Beach airport.

The program manager eventually offered Hernandez a spot in Rockwell’s co-op for young engineering students, and the teenager began working for the aerospace firm as a high school senior. Hernandez had initially planned to become a U.S. Marine, like his father, or a police officer, but chatting with Rockwell employees changed his mind.

“I didn’t know what an engineer was, so I started talking to them, asking them, ‘What is it that you do, how do you do it, what did it take to get to where you are,’” he said. “I said, ‘Well, this is not bad. I think I could do this.’”

An intriguing prospect

Hernandez later graduated from

In the early 1980s, Northrop Corp. bought Ford Motor Co.’s huge, vacant auto plant in Pico Rivera. No one knew what it would be used for but Hernandez’s mentors, including the program manager who recruited him, began to leave Rockwell for jobs at Northrop.

That program manager spent several years coaxing Hernandez to join him, giving no details about the job but promising it would be worth his while. In 1987, Hernandez finally relented, signed the required security forms and was escorted into a huge room with a high bay in the middle of Northrop’s Pico Rivera plant.

“There’s a curtain, and they pull the curtain back and right there is a full-scale wooden mock-up of the B-2 bomber,” Hernandez remembers. “She looked like she was from outer space. They said, ‘That’s what you’re going to work on.’”

Mr. Fix It

Hernandez’s 12 years in the B-2 program, including his time as chief engineer, taught him about the importance of solving problems. Early on, Hernandez and a small group led an analysis of a wiring issue on the B-2.

After briefing a three-star U.S. Air Force general and other top company executives and high-ranking government officials about the cause of the problem, Hernandez was asked when he would fix it. He tried to explain that he was only responsible for the analysis, but was told, “Now, you fix.” Hernandez and a group of engineers eventually re-worked the wiring for the B-2 to prepare the bomber for its first flight.

“I speak to young people on a regular basis and I say, ‘Figure out how to find things that are kind of messed up and jump in the middle of them and make them better,’” he said.

More success stories from How I Made It »

The more diverse the group is in solving a problem, the better the solution’s going to be.

— Chris Hernandez

Learning to listen

In the mid-1990s, Northrop sent Hernandez to the MIT Sloan Fellows program to get a master’s degree in management. His classmates came from all walks of life — an Air Force general, a future U.S. postmaster general — and from more than 10 countries. That gave “the kid from Norwalk” a broader perspective on the world.

When the cohort discussed topics, Hernandez found himself shifting his perspective based on his classmates’ arguments, rather than staunchly sticking to his own opinions. Now, when someone comes to him with an opinion, he tries to shut down his own thoughts on the topic and listen to their argument. If it’s more powerful than his own, he considers changing his mind.

“If everybody does what you want done, then there’s that absence of diversity in thought which companies strive for,” Hernandez said. “The more diverse the group is in solving a problem, the better the solution’s going to be.”

Second career thoughts

Four years ago, Hernandez seriously considered retiring from Northrop to become a high school math teacher. He had always thought his life’s mission was to help others; at Northrop, he was helping those who already made it. He hoped he could excite students about science, technology, engineering and math and give them a leg up, much like the Rockwell shuttle program manager had reached out to him.

Then he was offered his dream job — running a new organization within Northrop called NG Next, which would combine research and technology efforts with advanced design and rapid prototyping.

The organization can take an idea and develop it all the way to an early prototype. The group includes Scaled Composites, a cutting-edge Mojave aerospace firm that was acquired by Northrop. Hernandez now heads the research and technology component of NG Next.

“Having the engineering piece and the technology piece in this organization and then being able to watch things move from just an idea to a flight line, I just couldn’t say no,” he said.

Importance of music

Playing music is soothing for Hernandez. Around 2008, he bought a guitar at the urging of one of his two sons, Christopher, who wanted his dad to join him and his friends to play music. One year later, Christopher died in a car accident at age 17.

Hernandez began to take guitar lessons. He improved enough to join Christopher’s musician friends and put on concerts in his memory over the years for friends and family. He’s learned to play songs from some of Christopher’s favorite bands, and has also re-written lyrics from others, like Radiohead’s “High & Dry,” to honor his son.

“When I play, I can feel a connection with my son,” Hernandez said. “When I have any time extra, that’s what I’ll do — pick up the guitar and play.”

He said his son’s death helped him realize the importance of living in the present.

“Being comfortable with who you are and loving other human beings is a really, really good way to live,” Hernandez said. “Focus in the moment, be the absolute best you can be right now.”

Personal

Hernandez lives in Redondo Beach, though he frequently travels for his job and can also be found on his boat in San Diego. His son James lives in New York. Hernandez is also involved with the Mexican American Opportunity Fund and the advisory council of the dean of Cal State Long Beach’s college of engineering.

Twitter: @smasunaga

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.