When will the other shoe drop in U.S.-China economic relations

After an unexpectedly amicable start to U.S.-China relations under President Trump, including high-level economic talks Wednesday, many are wondering when the other shoe will drop.

Trump early on was preoccupied with the North American Free Trade Agreement and then on trade rivals such as Germany, largely giving China, the biggest U.S. trading partner, a pass.

Trump neither labeled Beijing a currency manipulator as he had promised to do, nor has he yet hit China with any significant sanctions. Why rock the boat, Trump has said more than once, if Chinese President Xi Jinping might help the U.S. rein in North Korea’s nuclear weapons program.

But the honeymoon may be over. It has become clear to Trump that China can’t or won’t deliver on North Korea, and the 100-day action period after Trump welcomed Xi at his Mar-a-Lago estate ended this week with some notable but overall modest results, including a reopening of U.S. beef exports to China and a little more access to Chinese financial markets.

All the while, the U.S. trade deficit in goods with China, by far the largest, has widened since Trump assumed office. This deficit is on pace to surpass $360 billion this year.

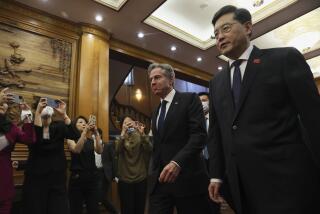

On Wednesday, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin hosted a Chinese delegation led by Vice Premier Wang Yang, continuing an economic dialogue that has spanned three U.S. administrations and marks the institutionalizing of commercial relations between the two largest economies, which account for one-third of the world’s economic output.

Yet amid the usual pomp and toasts hailing the importance of cooperation, there were indications of rising tensions. Ross opened the dialogue by noting that although U.S. exports to China had grown on average 14% annually over the last 15 years, Chinese shipments to the U.S. have soared as well to the point where the Asian country now accounts for nearly 50% of America’s overall trade deficit.

“It is time to rebalance our trade and investment relationship in a more fair, equitable and reciprocal manner,” he said, adding that “a fundamental asymmetry in our trade relationship and unequal market access must be addressed.”

Wang, obliquely responding to U.S. complaints about an uneven playing field, said that the two nations are at different stages of development. He added that “confrontation will immediately damage the interests of both.”

After the meeting, Mnuchin and Ross issued a statement saying, “China acknowledged our shared objective to reduce the trade deficit which both sides will work cooperatively to achieve.”

Both the American and Chinese parties earlier in the day abruptly canceled news conferences scheduled at the end of talks, with neither side explaining why.

Few analysts would be surprised at a deterioration of U.S.-China relations, given Trump’s harsh rhetoric on the campaign trail, when he bashed China’s mercantilistic practices and blamed its large trade surplus for the loss of American factories and jobs.

As president, Trump has continued to put trade front and center in his economic policy. But by making the trade deficit — its size and whether it is going up or down — the primary measure for judging bilateral economic relationships, Trump has put himself in a difficult position, economists said.

“It’s a strategy that’s almost certain to fail,” said Nicholas Lardy, a China economy expert at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

That’s because U.S. trade deficits are largely the result of the shortfall in national savings relative to investments — a long-running imbalance that isn’t likely to change any time soon. China’s share of exports globally, meanwhile, is growing as it steadily moves up the value chain. The U.S. dollar remains strong, making its goods relatively expensive in foreign markets. And although China’s Wang urged the U.S. to relax its export controls to sell China more advanced technologies, political pressures in the U.S. appear to be moving in the opposite direction.

“Everything is working against Trump’s announced objective,” Lardy said.

In promising China a better deal on trade if it tightened the screws on North Korea, Trump hoped to score a big short-term win in what has become an increasingly worrisome threat to the U.S. and its allies in East Asia.

For presidents, linking national security and foreign relations to trade is nothing unusual. But Trump overtly and repeatedly put the North Korea issue ahead of others, even though Asia analysts agree it was never realistic to expect China to dramatically ratchet up the pressure on Pyongyang.

More recently the Trump administration has threatened to sanction businesses and even countries doing business with North Korea. And the administration is finding it has little common ground with China on some other international issues.

Unlike Obama, who sought Chinese cooperation on restraining Iran’s nuclear program and the problem of global warming, Trump has pulled out of the Paris accord on climate change and this week slapped new sanctions on Iran after reluctantly agreeing to recertify that Tehran is complying with an international nuclear agreement.

“Those issues provided ballast to the relationship, and now we’ve lost that ballast,” said David Dollar, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and formerly the World Bank’s China country director.

Even so, Dollar believes there’s an underlying stability to the U.S.-China economic relations that is independent of the politics, borne out of three decades of investments and activity from businesses on both sides that are keen on preventing disruptions in trade and commerce.

In a U.S.-China business leaders’ meeting in Washington this week ahead of the two-nation economic dialogue, executives including chiefs of e-commerce giant Alibaba and U.S. multinationals like General Motors and JPMorgan Chase urged leaders of the two countries to resolve disputes through negotiations instead of resorting to remedies such as sanctions, which could trigger a trade war.

One action the Trump administration could announce soon is tariffs on steel imports, of which there is a worldwide excess thanks to overproduction in China. Trump officials are considering applying tariffs on the grounds that the imports present a threat to U.S. national security, but businesses and analysts alike fear such a move could prompt retaliation from China and other countries.

Andy Rothman, a former career U.S. Foreign Service worker in China who is now an investment strategist at Matthews Asia in San Francisco, said the Trump administration would do better to work on opening China’s markets further rather than focusing on the trade deficit or sanctions on steel and aluminum.

From Xi and the Chinese, Rothman said, “all the signs are that they want to have a good, stable and productive relationship” with Trump and the U.S. But like other analysts, Rothman is more dubious about where Trump stands on the matter, given the erratic and the conflicting signals from the White House on trade and from Trump himself.

“I was expecting him to come out of the gates on January 20th blasting at China, based on what he said during the campaign,” Rothman said. “All of a sudden he and Xi are buddies…. It’s hard to know what the deal is.”

Follow me at @dleelatimes

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.