The Player: Living inside the game of Comic-Con and what ‘activations’ mean for fandom

Imagine what might be the world’s largest escape room: Several blocks of a major American city have been taken over by a few monolithic corporations that not only control the space but dominate the culture. Currency is handed out as a reward for pledging allegiance. And everyone you meet is a potential friend or maybe simply a brand extension.

Welcome to San Diego Comic-Con International, where our stories and myths have been gamified. And you, the fan, are the protagonist.

Step into a transporter and be zipped and zapped to different “Star Trek” locales in about 30 seconds. Apply to be a cop on “Brooklyn Nine-Nine.” Venture into an underground hangout for gamblers and worse as reflected in the world of Epix’s “Pennyworth.”

You might take a stroll through a Victorian-era speakeasy where fairy-tale creatures mingle with burlesque performers, a full-scale representation of Amazon’s metaphorical take on race and immigration that is “Carnival Row.” Or, if you’re slightly braver, sneak through a detailed forest influenced less by any real-world locale than by the slasher movies of the 1980s in FX’s “American Horror Story”-themed walk-through.

These so-called activations — no longer unique to Comic-Con but popping up in cities around the country ahead of TV and movie openings — are one way elements of game design are reshaping fandom. But when rules are dictated by marketing plans, play comes with strings attached, and potentially for the creators as well. Exploring Comic-Con in 2019 is akin to delving into an open-world video game, where each minor accomplishment is broadcast with a digital achievement, a stamp-like figure affixed to one’s online profile.

Those who wait in multihour lines to, say, stand briefly in that makeshift “Star Trek” transporter, receive not just a mini video but a pin themed to “Picard.” A travel mug is your reward for waiting an afternoon to simulate going to space via a transporter ship from “The Expanse” only to arrive on what appears to be a hostile alien planet where actors impressively re-enact torture scenes and mini-fights. And, of course, each achievement unlocks something to brag about on social media.

But watch out. All sense of reality is obscured inside this world. Personalities and personality traits no longer have definable lines.

Fact or fiction?

In the midst of one pop-up immersive experience for a much-hyped new show, it appears that a lurid mystery is about to unfold.

A woman at the door stops me, points to another woman seated between two others on a couch. She suggests I talk to her, noting she’s the significant other of someone important.

A moment later I encounter a different woman, who tells me she is in fact the girlfriend of said important person.

Aha! The game, I think, is afoot!

Only it’s not.

“I was told the woman over there is his girlfriend?” I say to the second girlfriend, pretending to act slightly puzzled. “Oh, no,” says the now visibly confused actor in front of me. “I mean, maybe in real life? But here, and on the show, I’m his girlfriend.”

This “game” is clearly broken. But in the larger Comic-Con narrative, the character break makes sense. Fact and fiction, after all, are blurred regularly in the world of activations, to use the vague marketing lingo that has become the norm for these game-like pop-up experiences.

Activations have thrived for years at Comic-Con and elsewhere, even allowing non-registered guests to partake in the fan-focused festivities. Their goal is to give fans the illusion of participating in a narrative — or, failing that, to at least create a photo opportunity. At their best, they create a sense of lore, building out a world for those in the know. But even the best of these are advertisements that create a false sense of fan wish fulfillment.

A fan at Comic-Con International here had a message for Joss Whedon, creator of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and director of two “Avengers” movies: We want you back.

Yet the more entertainment conglomerates explore game-like activities, which give fans a greater sense of agency, the more they may have to come to grips with fans demanding a sense of participation. Each new walk-in experience brings us closer to a world where fan fiction is no longer relegated to the most passionate fringes but increasingly surrounds and may someday lead us. In a pop-culture landscape obsessed with franchises and proven intellectual property, some may wonder if we’re already there.

Perhaps that’s why for all the detailed environments that sprout around Comic-Con I feel an underlying sense of cynicism.

The primary notable feature for many activations is their wait time, as these experiences, rarely longer than five minutes but often much shorter, can accommodate only a few hundred per hour. This is a feature rather than a bug, as the fear of missing out is meant as much for those following along on social media as it is for those in San Diego. Besides, where fans tend to spend their afternoon is essentially a vote of confidence in a property — the Comic-Con equivalent of choosing which game to play in an arcade.

The fan’s role

Not all ads were created equal.

Amazon’s hidden speakeasy of fairies and bold singers for its upcoming “Carnival Row” succeeded in not only creating a sense of place but feeling of the moment, with authorities treating anyone who looked different as out of place and worthy of being detained. The cluttered cabaret was outfitted with hidden peepholes and nooks to have one-on-one conversations with the those acting. It was built from the ground up as a place for hiding, and I’ll be curious to see if the show succeeds in its sense of world-building.

For another upcoming show, “The Boys,” Amazon went more of an escape-room route with a crime scene cover-up, but here too there were surprises, including some allusions to class warfare since the show is set in a world where superheroes are seen as privileged brats. Only some, for instance, would uncover a password that led to a secret comic book shop next door, a place where attendees could get more free swag.

Epix’s bar takeover for “Pennyworth” resulted in a lush environment where one could play cards or get a photo of being fake-tortured, but there was no underlying story to the experience, at least not one I uncovered. When I asked a member of the cast what kind of an establishment would allow for an electric chair in the backroom, she said I’d have to tune in to the show Sunday evening, essentially putting up a “game over” screen.

On the ground in San Diego, fans raved about FX’s work for a scary installation for the upcoming season, here shown as a parody of 1980s horror films set on a campground. Though the experience ended on a cliffhanger, the campy acting contrasted with a few jump scares — as well as the requisite chainsaw attack — that seemed to satisfy most, even if it meant sacrificing most of the day to see it, as waits early in the day could hit three-plus hours.

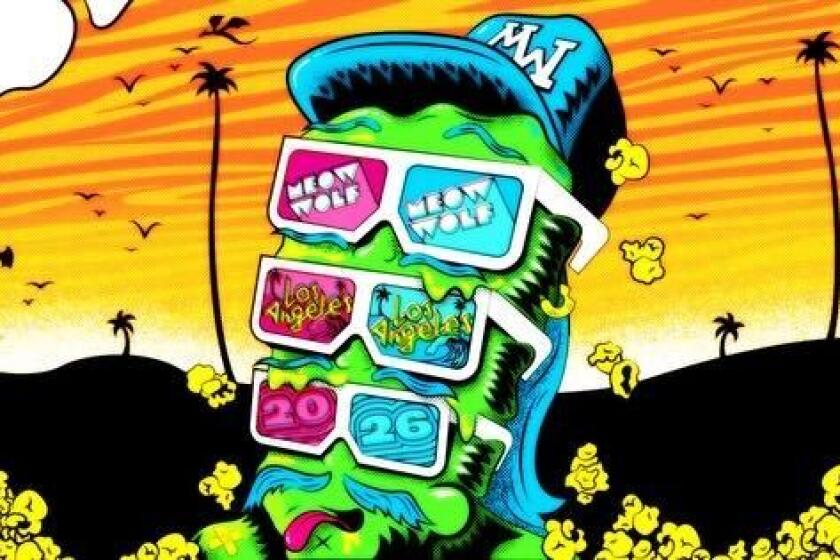

While it might be unfair to place the weight of criticism upon marketing endeavors, it’s worth noting that generally all miss a key tenet of immersion-based gameplay, which today is going mainstream thanks to practitioners such as the New Mexico-based Meow Wolf art collective, building out spaces in Las Vegas and Denver, and role-playing theme park Evermore outside Salt Lake City, not to mention the participatory nature of Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge at Disneyland.

Most pop-up brand experiences don’t need audiences on their terms, acknowledging that the participant is something of an outsider. In turn, it may be a playing field, but it’s on guard rails — stand here, look at that, talk about this. At a jovial Evermore panel at Comic-Con, a fan asked how the park was different from a Renaissance fair, and the answer was simple: The park’s 50-plus cast aren’t there to sell you something. After all, if you’re playing you already bought in, so they exist simply to help you find a place in the universe.

For most brand activations, however, if you step back to observe, the environments can appear relatively empty, and even slightly contentious, as if neither side fully trusts each other.

And maybe they shouldn’t. Creators are having to decide whether they will bow to fan demands (see the uproar, and subsequent delay, relating to the “Sonic the Hedgehog” film, or the defense by the cast of the final season of “Game of Thrones”). Today, petitions against creative decisions occur with such regularity on Change.org that it’s only a unique story when there isn’t outrage.

Such is the landscape that gaming culture has gifted us, where it isn’t unheard of for fan gripes to lead to content changes (see the ending of “Mass Effect 3”) and where we stand by our pop allegiances with the same fervor we take to a playoff game. Indeed, fans have become as invested in pop art as they are in their hometown sports teams, with social media debates about acting or directing decisions becoming as heated as those over the latest Dodgers or Lakers signing. No wonder Marvel Studios came to Comic-Con with announcements rather than content for its upcoming roster: Everyone is cheering when the starting lineup is being read.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.