Donald Margulies’ multiculti holiday tale

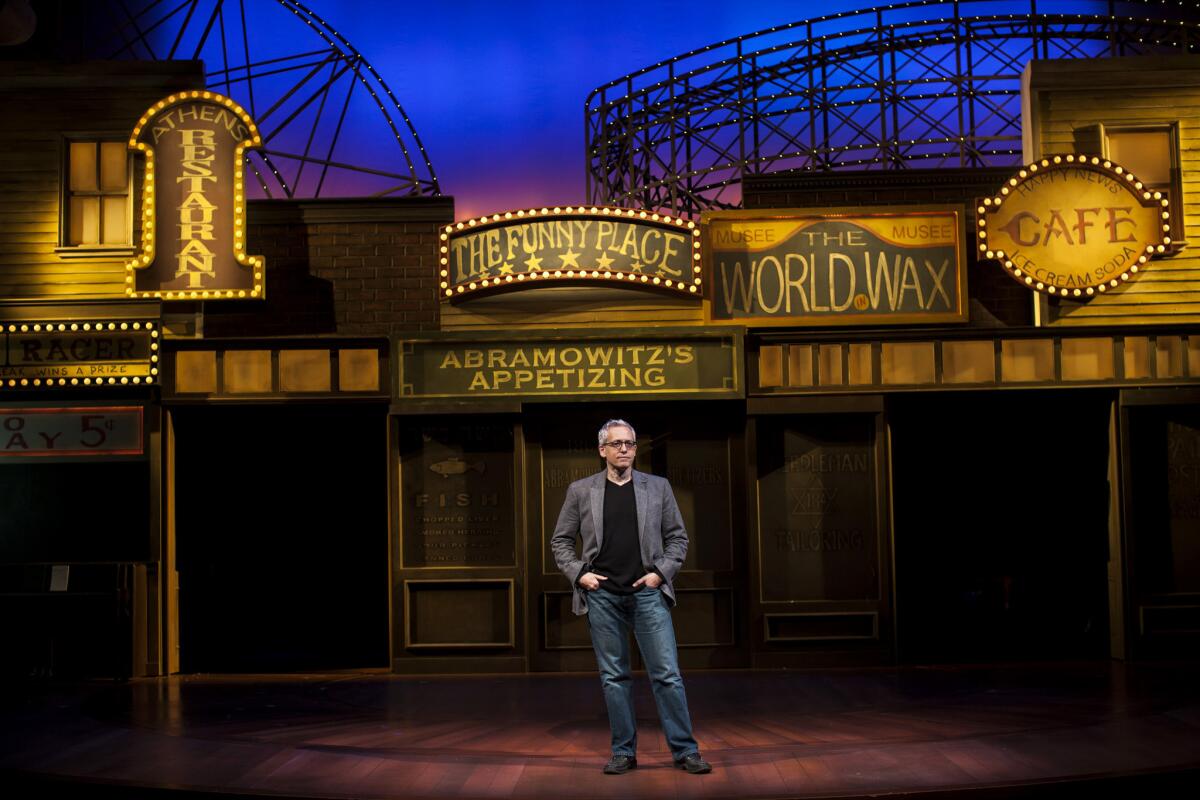

Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Donald Margulies talks about his inspiration for his new play, “Coney Island Christmas,” which runs through Dec. 30 at the Geffen Playhouse.

Tell me about “Coney Island Christmas.”

“Coney Island Christmas” originated as a commission by the late Gil Cates, who was the artistic director of the Geffen Playhouse and a friend of mine. He called me a few years ago and asked me if I would be interested in writing a Christmas play. He was hoping to create something that he hoped would become a theatrical tradition at the Geffen.

PHOTOS: Celebrity portraits by The Times

Why did he think of you for that?

The invitation came around the time that the Geffen produced my play “Shipwrecked! An Entertainment,” which was really a romp, a celebration of theater and storytelling intended for all audiences. And I think on the basis of “Shipwrecked!” he thought I might have fun with conceiving of such a Christmas play for the Geffen. I half-jokingly said to him, “You realize that if I write you a Christmas play, it’s going to be a Jewish Christmas play.” And he said, “Great.”

Then several months later I remembered a short story by the late great short-story writer Grace Paley. “The Loudest Voice” is about a girl named Shirley Abramowitz, who’s telling the story of herself as a young girl in Depression-era Brooklyn. She describes her drama teacher choosing her to be Jesus in the school play because she has the loudest voice. I thought the premise was so delicious that I would have a lot of fun with it, and I have.

There’s been more of a focus recently on the country’s diversity, and your play revolves around how non-Christians deal with the biggest holiday of the year. What kinds of conflicts does that bring up?

It occurred to me that the play actually had a timely element. It touched on the immigrant experience in America, and it seemed that with the recent election there was so much harsh language about immigrants in the political rhetoric. In the play Shirley’s parents respond differently to the invitation that her drama teacher made for her to play Jesus. Her father is more accepting of an assimilationist point of view, and her mother is quite threatened and horrified by it. The Grace Paley story has no conflict in it.

Your play deals with the religious component of Christmas, but the holiday has grown beyond that into the biggest celebration of the year. Do you have any thoughts about where that leaves non-Christians?

Part of what the play embraces is the kind of pan-cultural aspect of America, really viewing Christmas not so much as a religious holiday but as a time to reflect and a time to celebrate family and values — yes, they could be Christian values, but they certainly are humanist values. I think it transcends Christianity. It doesn’t have quite the same value obviously to non-Christians, but it’s a kind of national holiday.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures

Do most of the non-Christians you know celebrate Christmas in one way or another?

Yes, in some way or another. I’m married to a non-Jew. We’ve had Christmas trees, we have a hybrid son. It doesn’t feel like a shonda for the goyim [something shameful witnessed by non-Jews], the tree. It’s more celebratory of the passage of another year. One of the things I try to do with “Coney Island Christmas” is to shift the focus from the religiosity and talk more about the cultural melting pot of America in positive terms, which I think have been eclipsed recently by a certain stridency in our politics.

How did your family handle Christmas when you were growing up?

I grew up in a lower- to middle-class household. My father sold wallpaper, my mother was a housewife for most of my childhood. We were not observant Jews. We didn’t go to synagogue, but we did go to Broadway. And there was certainly cultural identity. My grandparents spoke Yiddish, I had neighbors who were Holocaust survivors, and I went to Hebrew school and was bar mitzvahed. And we weren’t a terribly celebratory family. My parents didn’t make a big deal about birthdays and Hanukkah.

What did your family do then on Christmas?

We got Chinese food like most Jews in Brooklyn.

How are you going to spend this Christmas?

Well, my son is coming home from college. We’re just going to hang out at home. We might have a tree. We have friends with whom we celebrate Passover every year; they come to us for Christmas Eve every year. And that often consists of takeout Chinese food as well. So the tradition lives on.

You said in an interview for your play “Brooklyn Boy” in 2005 that earlier in your career you made a conscious decision to leave Brooklyn behind in your work. What happened and what keeps drawing you back?

My early plays dealt much more directly with my Brooklyn Jewish upbringing. They were my coming-of-age plays, my Jewish son and artist plays. And with my play “Sight Unseen,” it felt unconsciously as if I had crossed the bridge figuratively from Brooklyn into the world. And I decided that I would see what that brought, being not just the son and artist but being the man who has come of age and what the larger world brings. So it was in that phase of my career that I wrote “Collected Stories” and “Dinner With Friends.”

“Brooklyn Boy” came out of a conversation I had with my friend the late [playwright] Herb Gardner, who was a fan of my early Brooklyn plays and wondered why I wouldn’t try going back to Brooklyn now that I’m an adult.

You’ve done a lot of work on both coasts. Do you see a difference in audiences on either coast?

I don’t really see that much of a difference in audiences from coast to coast. What is striking is the audiences tend to be older generally. Young people don’t necessarily think of going to the theater. There’s so much entertainment available at one’s fingertips and in all different modes that theater is not the primary destination for younger people. And I think that the nature of the economy right now and the high cost of going out to the theater has made it so prohibitive for middle-class families to make it a family venture. Theater is just becoming increasingly arcane. So part of my objective in writing plays like “Shipwrecked! An Entertainment” and “Coney Island Christmas” is [creating] a way to invite families back into the theater together.

You also teach playwriting at Yale; has the economy had an impact on your students as well?

I don’t actually see a decline in interest in playwriting. Last fall, when I accepted applications to my 12-student seminar, I received something like 56 applications, which I think shows a very healthy interest in theater. That is a higher number than I’ve seen in the last couple of years. So maybe that’s a reflection of more optimism about our economy. I think a lot of my students have done very well straight out of Yale and are now writing movies and television and plays. And that’s very gratifying for me. It’s a wonderful thing to see all these acolytes out there.

MORE

INTERACTIVE: Christopher Hawthorne’s On the Boulevards

VOTE: What’s the best version of ‘O Holy Night’?

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.