Review: The L.A. Phil’s Minimalism marathon

- Share via

Minimalism, the musical version, has always been a numbers game. It began with extended tones, with beats added and subtracted to phrases at will and with simple rhythms played in and out of phase to create complex patterns.

So let’s have some numbers for the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s extraordinary Green Umbrella marathon Tuesday night at Walt Disney Concert Hall, part of the orchestra’s Minimalist Jukebox Festival.

The concert lasted five hours if you count a pre-concert discussion and a pre-concert performance. There were 14 pieces by 11 composers played by five ensembles, three conductors and two soloists in four parts of Disney.

PHOTOS: Best classical concerts of 2013 | Mark Swed

But math and music can be a funny business.

In a new book “Love & Math,” Edward Frenkel writes that a mathematical formula or theorem “means the same thing to anyone anywhere — no matter what gender, religion, or skin color; it will mean the same thing to anyone a thousand years from now.”

What made this Green Umbrella marathon so compelling is that the mathematical underpinning of Minimalist music means something different to every composer. Gender, religion and skin color might matter. Minimalism today is not even vaguely the same thing it was four decades ago, nor is it played the same way.

The evening began with purity, but that didn’t last long.

As the audience entered the auditorium, pianist Richard Valitutto was playing William Duckworth’s “Time Curve Preludes,” works of deceptive simplicity.

Flutist Claire Chase, founder of the Brooklyn-based International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE), which was one of the groups participating, played Steve Reich’s “Vermont Counterpoint” on a variety of flutes backed up by 10 pre-recorded flute parts. Basic melodic shapes moved in and out of phase, making all of Disney feel so immersed in the essence of flute you could almost sense the spit.

PHOTOS: Faces to watch 2014 | Classical music

Yet Minimalism can also be intensely personal. Julius Eastman’s “Stay On It” was played by the young L.A. ensemble wild Up (like ICE, making its Disney debut). Eastman, who died in 1990, was a Minimalist apart, an African American gay activist, a marginal composer better known as a singer and pianist who is being rediscovered. This 1973 piece, harsh and driving and bursting into episodes of free jazz, turns out to have been radically ahead of its time. Christopher Rountree led a riveting performance.

Reich’s “Different Trains,” the composer’s autobiographical string quartet accompanied by recorded voices of train conductors from his boyhood of shuttling between the East Coast and the West at the same time other Jewish boys on trains in Europe were headed to a horrifically dissimilar fate. It was played by the Calder Quartet with an engrossingly rich tone and rhythmic acuity that revealed what may be an overlooked Minimalist root in the Eastern European folk-inspired music of Bartók and Janácek.

David Lang’s “death speaks” looked to Schubert’s way of personifying death in his art songs. Death here speaks in the honeyed, haunted folkish voice of indie-pop singer Shara Worden, who quivers on few pitches. Her pointillist accompaniment was by pianist Nico Muhly, electric guitarist Gyan Riley and violinist Andrew Tholl.

Reich’s most recent piece, “Radio Rewrite,” expertly played by ICE if over-emphatically conducted by David Fulmer, is also pop-centric, taking two Radiohead songs as the basis for harmonic and melodic material. You have to listen hard for bits of “Everything in Its Right Place” and “Jigsaw Falling Into Place,” but the thick chord progressions and the long melodic lines over pulsating rhythms, all trademarks of the composer, were everything in their Reich place.

PHOTOS: LA Opera through the years

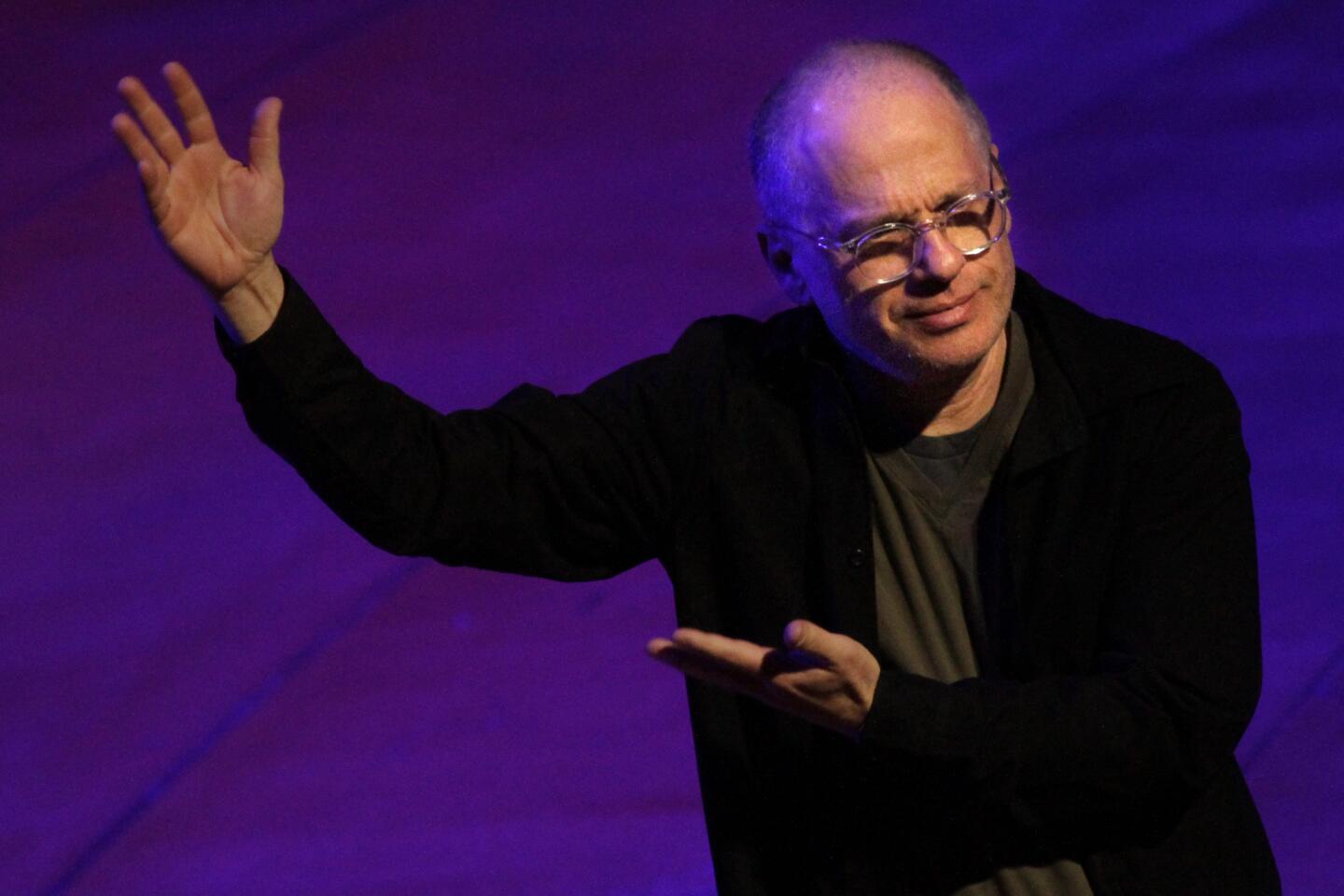

Two new pieces, Mark Grey’s “Awake the Machine Electric” and Missy Mazzoli’s “Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres),” were commissioned for the occasion and written for the L.A. Phil New Music Ensemble, conducted by John Adams. They had little in common with Minimalism or each other, with the exception of the wideness of scope.

Grey’s “Machine” was the result of a trip to Perm, formerly Molotov, Russia. Once a center for Soviet munitions manufacture, it led Grey to the creation of a kind of musical Molotov cocktail, mercurial and madcap. Sometimes Coplandesque pastoral, sometimes chugging Adams-like and sometimes employing old sci-fi electronic sound effects, this is an addictive score ever changing from minute to minute.

Mazzoli’s is music not so much of, as out of, the spheres. Strings and winds swirl and swoon, sliding magically around pitches. There is no pulse, no thousand points of starlight, rather the motion of waves. She manages to squeeze in the hurdy gurdy without ever losing the sensation of gorgeous celestial bodies in the ether.

The Sinfonia lasted 14 minutes and came near the end of a long concert that went to midnight. But this is music for a long night that never ends.

Andrew McIntosh’s “Silver and White” also had that otherworldly sense. A violinist and violist in wild Up, he explored microtones and the way they altered perception — a trumpet onstage sounded to me as though it were somewhere in the balcony.

The concert ended with what appears to have been the first performance of Adams’ chaotic “American Standard” in 40 years, which wild Up dug up and made a new version of to the composer’s apparent bemusement.

Adams’ personality can be recognized in the fascinatingly disparate musical elements. Once he became a Minimalist, he made it all work.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.