Review: Monday Evening Concerts explores Beckett’s ‘Words and Music’

Words and music are stuck with each other. Like it or not, they have to get along.

Untrusting of only our ears, we attempt to understand music through words. Words, in song, challenge music to give them new consequence. And, in great writing, words themselves aspire to the state of music, pregnant with something more than mere meaning.

Samuel Beckett was such a great writer, and his 1961 radio play “Words and Music” is his unnerving look at this fraught relationship. No music could be found to properly suit it until the Irish writer asked Morton Feldman for a score in 1985, when NPR wanted to produce it (those were the days for Public Radio).

The resultant work is sublimely disquieting, so much so, perhaps, that it is seldom performed. But Monday Evening Concerts began its 75th season with it Monday night at Zipper Concert Hall at the Colburn School. This is a historic anniversary for the nation’s longest surviving concert series. Beckett and Feldman make it especially so.

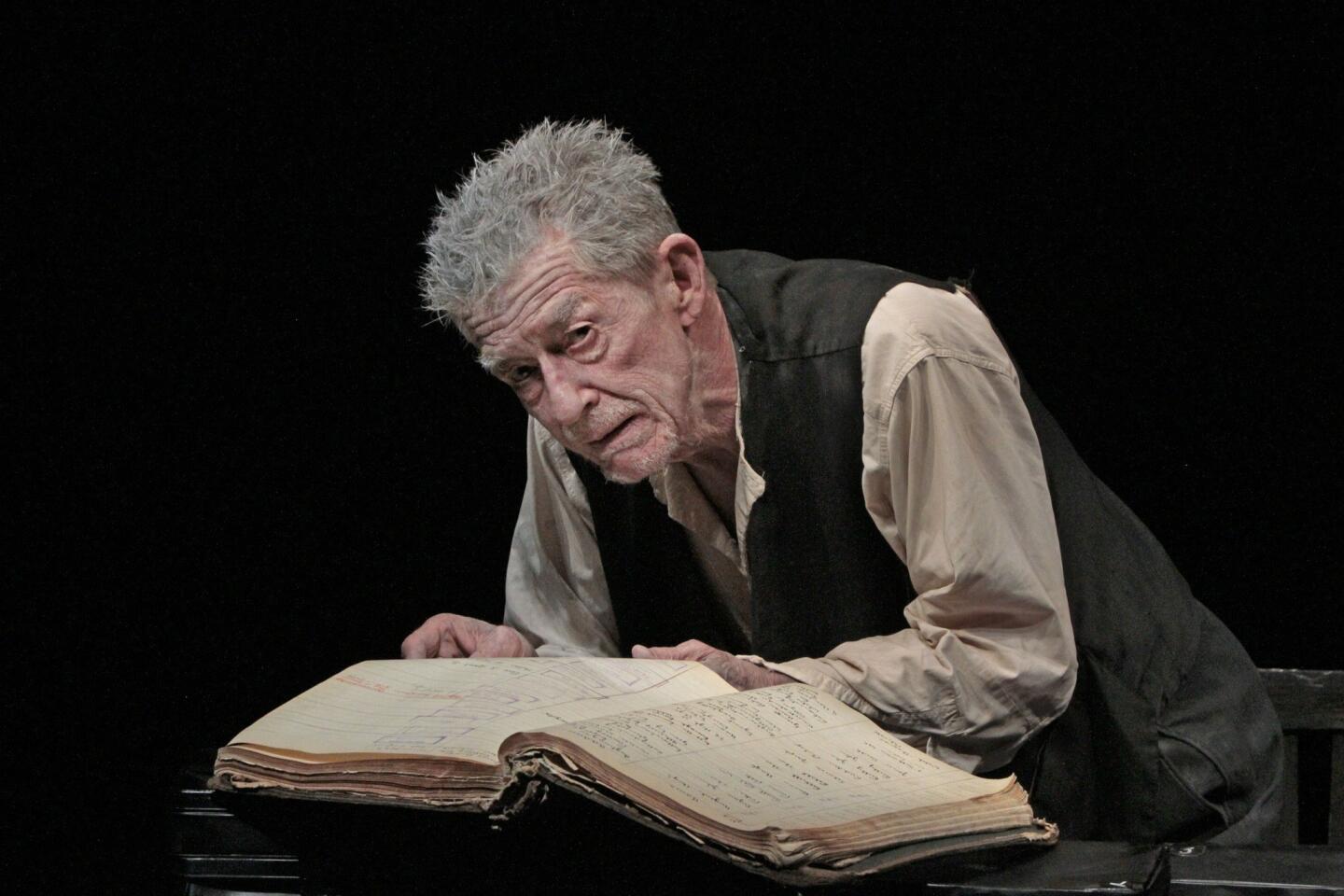

Music and Words are characters in Beckett’s play, which lasts about 40 minutes and begins with the sound of tuning up, already annoying Words. He wants to talk about sloth. An old man, Croak, is a go-between. Joe and Bob, the kind of pair who might be waiting for Godot, also personify words and music.

Feldman’s solution is to divide the parts between two reciters — Words and Croak. The score is composed of 33 short segments for seven players (two flutes, string trio, vibraphone and piano) that feels like a through composition of repeated radiant chords shot through with incandescent bell-like effects from the percussion and plucked strings.

PHOTOS: Operas by Philip Glass

Sloth, sex and old age — common terrors in Beckett’s reflections on relationships — are the obsessions of Words. Sentences are quickly strung together or broken apart in stinging cadences. Old age is: “Waiting for the hag to put the … pan … in the bed.” Music teaches Words to put that into song. By drawing attention to wondrous sounds, Feldman’s score teaches us to hear the music already in Beckett’s words. Settled music doesn’t so much accompany unsettled text as aerate it.

Jonathan McMurtry (Words) and Jamie Newcomb (Croak) read their lines seated. They were understated but personable. Kim Rubenstein was the director. I would have liked a little more savoring on the delicious awfulness of some of Beckett’s imagery and maybe something a tad juicier in the nasty sex business. But you got the point, and Feldman’s music, which was conducted by Jonathan Hepfer and excellently played by a pickup ensemble, aerated splendidly.

The program began with more unusual music, two pieces from the mid-1970s by Jo Kondo perfectly suited to the occasion. There is no good reason for our not hearing more of the strange music by the 66-year-old Japanese composer, who was influenced by and championed by Feldman and is a major figure in Asia.

ART: Can you guess the high price?

“Slight Rhythmics,” which began the program, is for banjo, steel drum, electric piano, tuba and violin. Few notes are used in its six sections, which contain no strong pulse and continually repeat with only occasional changes in pitch, an instrument at a time. The combination of conspicuously arresting timbres and numbing repetition can be curiously invigorating.

“Under the Umbrella” is odder still. It is for 25 cowbells played by five musicians (the percussion ensemble red fish blue fish). The sound is spectacular, something like the glitter of a loud prepared piano. It goes on for 25 minutes, ringing, ringing, ringing as if magically forever.

Since the subject in this concert was words and music, I defer to the composer. The program notes describe Kondo as having been inspired by an image on television of an Indian Buddhist priest walking slowly beneath an umbrella held by an acolyte.

“What I felt appropriate about the title for the music,” Kondo then notes with Beckettian flair, “lies something between the Buddhist monks and ‘Singin’ in the Rain.’”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.