Review: Noel Coward’s ‘Song at Twilight’ is an overlooked gem

Accustomed to living glamorously in the spotlight, Noël Coward conducted his private affairs, in the words of writer Rebecca West, “with an impeccable dignity … which was reticent but untainted by pretense.”

Given that homosexual acts weren’t decriminalized in Britain until 1967, Coward’s glass-door closet wasn’t just a witty place to be — it was also a fairly courageous one.

But attitudes were rapidly changing. “Homosexuality is becoming as normal as blueberry-pie,” Coward observed in his diaries in 1960. And in “A Song at Twilight,” produced in London in 1966 with Coward starring in the role of closeted aging author Hugo Latymer, he directly confronted the subject he had spent his career sophisticatedly skirting with knowing winks and glancing repartee.

PHOTOS: Best in theater for 2013 | Charles McNulty

The play, which opened Sunday at the Pasadena Playhouse in a stunning production directed by Art Manke, is part of Coward’s late-career offering “Suite in Three Keys,” a trilogy set in a hotel suite in Switzerland so luxurious one would eagerly submit to any manner of high drama for the chance of staying there.

Although its dialogue has the epigrammatic polish that is Coward’s trademark, “Song” isn’t as comically fizzy as “Private Lives or “Hay Fever.” There’s a bit too much exposition in the first half, and the structure, while extraordinarily fluent, is old fashioned.

But the drama grapples candidly with the costs, both psychological and artistic, of repression. Manke’s sumptuously designed and supremely well-acted production makes a case for this being an overlooked gem in the Coward canon.

Coward intended the work as a vehicle for his farewell appearance on the stage. He got the opportunity in London, though he was unable to perform in New York. (A year after Coward’s death, on a bill titled “Noël Coward in Two Keys,” a shortened version of “Song” had its 1974 Broadway premiere with “Come Into the Garden Maud.”)

The role of Sir Hugo, preening literary lion, has a distinguished pedigree, having been inspired by an incident that happened to Max Beerbohm and modeled in part on the character of W. Somerset Maugham. The parallels with Coward’s own life are unmistakable. Indeed, he spares himself little in this self-interrogating quest.

PHOTOS: Faces to watch 2014 | Theater

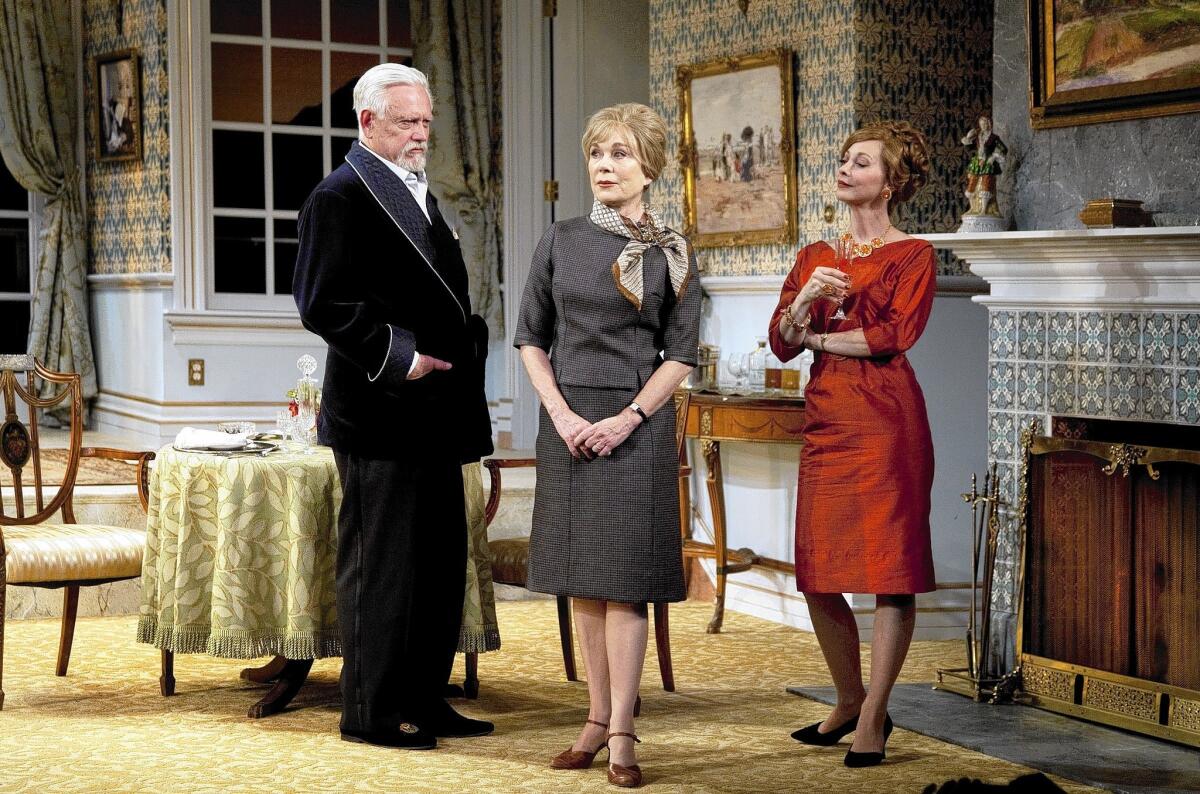

While convalescing in Swiss splendor, Hugo (distinguished veteran Bruce Davison, nominated for an Oscar for his performance in “Longtime Companion”) is attended to by his commandingly efficient German wife and secretary, Hilde (the redoubtable Roxanne Hart, nominated for a Tony for her performance in “Passion”).

A figure from the past intrudes on their posh routine: Carlotta Gray (the excellent Sharon Lawrence, recipient of multiple Emmy nominations for her work in “NYPD Blue” and one more recently for “Grey’s Anatomy”). His mistress from long before he met Hilde and an actress who never quite became the star others thought she’d be, Carlotta has just written her memoirs and has come seeking permission to publish the love letters he wrote to her 40 years ago.

Obsessively controlling when it comes to his reputation, Hugo declines in his characteristically snappish style while the two are dining together alone in his suite. Carlotta is dismayed but she has another card to play: She’s in possession of letters Hugo wrote to the man who was the love of his life. When the lights go down at the end of the first act, poor Hugo looks like he could use a defibrillator.

The situation may sound melodramatic, but Coward handles it with melancholy restraint. The plot interests him only to the degree that it forces the characters to reckon with their hidden selves. Yes, husband, wife and former mistress have all been harboring secrets about the nature of their love. If this were a triangle, it would be an equilateral one, so balanced are the sides.

Hugo is more anxious about how the revelation of his homosexuality might affect his reading public than what it will do to his sturdy, passionless marriage. His reputation has always been the main driver of his action, but now that intimations of mortality are besetting him his legacy is especially important to him.

PHOTOS: Hollywood stars on stage

Davison’s Hugo, dressed in an elegant smoking jacket and firing off rejoinders with scornful impatience, has cut himself off from his emotions for so long that he has to surmise what he once used to feel. His character is an admixture of intelligence and benightedness, aggression and fear, cynicism and regret. He argues eloquently in defense of his own compromises, but it’s the numbed loneliness under his forceful words that tells the real story.

Lawrence’s strikingly beautiful Carlotta is a worthy antagonist. She may not be as verbally acute as Hugo, but she’s more psychologically incisive. Her motivation for coming back, too laden with history to be described as blackmail, is laid out with exquisite emotional lucidity. Lawrence’s performance finds unseen depths in lines a lesser actress would blithely glide over.

Hart’s Hilde, a source of terrific comedy, reveals herself to be more than just a dutiful wife with a Teutonic genius for organization. Her character grows in stature before our eyes, remaining one step ahead of the others even as she accepts her less-exalted role in the background.

Manke’s staging is magnificent to look at. Tom Buderwitz’s set has an Old World opulence that is the perfect backdrop for David Kay Mickelsen’s aristocratically splendid costumes. Zach Bandler’s handsome hotel waiter adds a suave touch to the overall allure.

This production of “A Song at Twilight” is a reminder that there’s more to Coward than Champagne bubbles and intoxicating quips. What could very easily have turned into a vintage case study of a closeted homosexual writer becomes a probing exposé of the concealments and deceptions that keep our most intimate relationships — with ourselves as well as with others — hauntingly unresolved.

‘A Song at Twilight’

Where: 39 S. El Molino Ave., Pasadena

When: 8 p.m. Tuesdays-Fridays, 4 and 8 p.m. Saturdays, 2 and 7 p.m. Sundays. Ends April 13.

Tickets: $44 to $64

Contact: (626) 356-7529 or https://www.PasadenaPlayhouse.org

Running time: 2 hours

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.