Review: Alison Saar traces diasporas in the exceptional ‘Silt, Soot and Smut’ at L.A. Louver Gallery

When the Great Mississippi Flood displaced hundreds of thousands of African Americans in 1927, many chose to keep on going. Impelled by the waters of the worst U.S. flood ever recorded, they joined another rising tide — a mass migration from the rural South to the urban Northeast, Midwest and West.

Cultural diaspora has been a prominent theme for sculptor Alison Saar for a long time, and it is a centerpiece of her magnificent new show at L.A. Louver Gallery. Displacement drives the monumental, 12-foot tall “Breach (large figure on raft),” a powerful nude figure balancing all her belongings atop her head. And it animates “Silttown Shimmy,” a smaller but no less potent pedestal sculpture of a woman wrapped in her own embrace.

“Breach” can be seen as specifically evoking the 1927 flood narrative, its lifesize figure poised atop a raft and using a pole to navigate the way. Saar positions her on a shallow plinth of wooden slats stained a mossy green, low enough to bring her face to face with a viewer but elevated on a pedestal nonetheless, suggesting eminence. A sturdy tower of strength, she carries with her an impossibly balanced stack of steamer trunks, suitcases, a frying pan, bucket, lantern and more domestic objects.

But Saar’s composition also disperses down related paths. The woman’s warm, sensuous, tactile brown skin is made from rusted plates of embossed ceiling tin, a uniquely American material. Her naked pose recalls Jim guiding Huck Finn down the Mississippi in a tale of conflicted yearning and liberation.

She’s likewise a New World caryatid, a personified pillar that held up the entablature in ancient Greek temples, such as the Erechtheum on the Acropolis. Their perhaps apocryphal association with slaves floats into view. So does the horrific Middle Passage and the Atlantic slave trade.

The 19th and 20th century diaspora is but a recent chapter in a very long history. Through the potent dignity of “Breach,” Saar commands it.

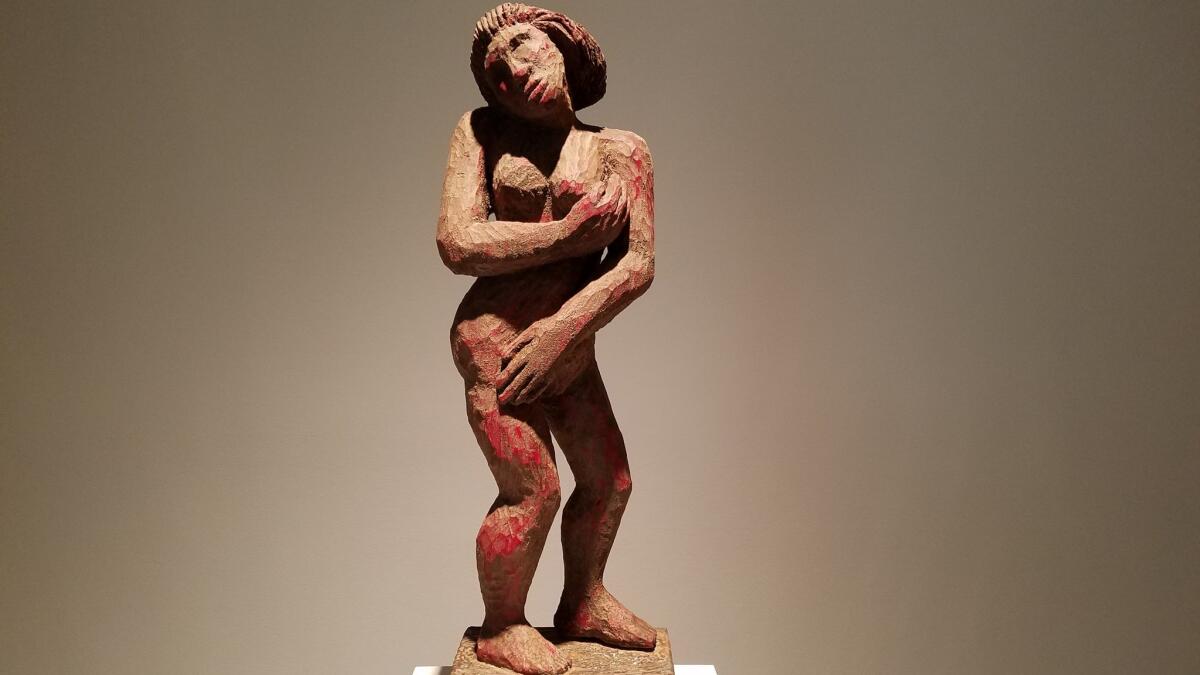

“Silttown Shimmy,” a totemic female figure a bit more than 2 feet tall, further elaborates. Saar’s sculpture merges profile and frontal views, its head tilted sharply toward her shoulder.

Carved from wood, its blocky base sheathed in ceiling tin and then rubbed with enamel paint, tar and silt to create a voluptuous patina, the nude female cups her left breast in her right hand and rests her left hand across her body on her right thigh, like the pose of a Venus from the ancient or Renaissance world. (Think Botticelli.) The gestures conceal her sex and fecundity yet simultaneously draw attention to those attributes, both physical and conceptual.

The shimmy, a dance born of black American ragtime music, underscores the work’s inescapable visual relationship to “Dancer With Necklace,” the great 1910 Ernst Ludwig Kirchner sculpture that is a landmark of German Expressionist art. (It was acquired last year by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.) The Kirchner carving was inspired by his frequent visits to Germany’s Ethnographical Museum Dresden to learn from Cameroon sculpture.

Saar’s oblique reference to it reminds us that European Modern art in the early 20th century is unthinkable without its profound, complex relationship to Africa. She brings artistic diaspora into play.

She also introduces current events, with water as the continuous theme. “Hades D.W.P.” is an illuminated wall shelf that holds five etched-glass jars, one for each mythological river coursing through ancient visions of hell. (They loosely recall Kiki Smith’s 1986 sculpture of etched glass jars for assorted bodily fluids.) Each of Saar’s has a battered ladle or drinking cup, and their internal illumination makes these water-filled jars glow with ominous radiance.

In “Hades D.W.P.,” water and power intertwine. Poisoned drinking water from the Flint River in the black-majority city of the same name in Michigan is yet one more unspeakable episode of abuse. Saar etched dead and dying bodies into the glass.

The show includes five additional sculptures, several of them sinuous figures emerging from ceramic jugs like escaping spirits, and 15 drawings and paintings on collaged surfaces, including steamer trunk drawers, sugar sacks and patched denim.

At 60, Saar has been making exceptional work for quite some time. A full museum retrospective is overdue.

------------

L.A. Louver Gallery, 45 N. Venice Blvd., Venice. Through July 1. Closed Sunday and Monday. (310) 822-4955, www.lalouver.com.

christopher.knight@latimes.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.