Natalia Osipova, Ivan Vasiliev bring ‘Solo for Two’ to Segerstrom

Known for their performance intensity, gravity-snubbing jumps and hurricane-force pirouettes, former Bolshoi Ballet stars Natalia Osipova and Ivan Vasiliev constitute a partnership that has created more buzz than nearly any ballet dancers since the Soviet defectors of the 1960s and ‘70s. The Russian duo — “Vasipova” to some — will debut their contemporary program, “Solo for Two,” at the Segerstrom Center for the Arts this week.

Osipova, 28, born in Moscow, and Vasiliev, 25, from Vladivostok, Siberia, were promoted to principal dancers at the Bolshoi Ballet in 2010 and became a sensation with their bravura flash in ballets like “Don Quixote.” But the two shocked the ballet world when they resigned from the company in 2011, citing a need for more artistic freedom. They initially jumped ship to the Mikhailovsky Ballet in St. Petersburg; eventually Osipova joined the Royal Ballet as a principal ballerina, and Vasiliev became a principal dancer with American Ballet Theatre.

While Osipova, with her aerial lightness and unbridled energy, has excelled in roles like Giselle and Juliet, Vasiliev’s appeal emanates from his sexy charisma and macho strength, making him a natural in ballets like “Spartacus.” Still, their daredevil approach and space-devouring capacity to make any stage look small often makes them exponentially more interesting together, even if theatrics have sometimes trumped classical refinement. Although they were once engaged to be married, their romance is now over and their relationship centers on work and friendship.

“We’ve been dancing together so long, and that chemistry has been with us all the time,” says Vasiliev by email. “That fire — it’s never happening with other ballerinas.” Osipova says that their rapport came easily, “maybe because we’re both perfectionists. And from our very first performances we always had something that makes us a great couple on stage.” She also adds, “I miss Ivan. I look forward to working with him and doing something that we’ve never done before.”

Osipova and Vasiliev performed at the Segerstrom Center with the Bolshoi Ballet in 2010. Osipova also starred in ABT’s premiere of Alexei Ratmansky’s “Firebird” there in 2012, and Vasiliev was one of the “Kings of the Dance” in 2011.

Premiere works

To showcase a different aspect of their artistry, they chose not to include any pyrotechnical warhorses on the program but instead will premiere works from three prominent international contemporary choreographers — Ohad Naharin, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui and Arthur Pita. They are in demand as guest artists around the globe and will perform “Solo for Two” in London in August and partner up for “Don Quixote” with the Mikhailovsky Ballet in New York in November.

“I think it’s obvious that we can dance any classical repertory somewhere else. Bolshoi, Mariinsky, Royal Ballet, Mikhailovsky Ballet, La Scala and ABT are always open for us in the classical repertory,” says Osipova by email.

“Both of them can create sublime moments,” says Naharin, the artistic director of Batsheva Dance Company, Israel’s premier contemporary troupe, by phone. “This is very rare, and it’s what turns me on when I see dance. It’s the difference between sublime and beautiful. I don’t fall in love with my choreography, but I fall in love with my dancers.”

In his choreography, Naharin uses Gaga, his own movement language that focuses on layered movements that explore the dynamics between effort and release or plasticity and sharpness. Osipova and Vasiliev traveled to Tel Aviv for 10 days to take classes with the Batsheva company and immerse themselves in Gaga.

They have continued the process, rehearsing with Batsheva dancer Rachael Osborne this month in residency at the Segerstrom Center, which co-produced “Solo for Two,” with Ardani Artists. “During rehearsal we’ve been like a sponge learning everything,” says Vasiliev. “We allowed our bodies to relax and accept the new style.”

Naharin expanded one of his works into the 20-minute “Passo” (meaning “step” in Italian) for the couple. The choreographer insisted they rehearse without a mirror, normally considered an essential tool for dancers’ self-critiques. “They have to gain the pleasure and the scope of sensation in listening to their bodies and get the clarity of form they can’t get from the mirror,” he says.

“Passo” is set to a taped score by the British electronic music duo Autechre with additional English traditional folk music. Nonetheless, says Naharin, the mood of the piece emanates from the dancers’ internal beat: “All the groove and rhythm of the choreography comes from the dancers. They don’t illustrate the music, and I don’t try to illustrate it. The music supports whatever their mood is and allows for an enlarging of the space.”

A choreographer of Belgian and Moroccan descent, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s movement incorporates ballet, modern, hip-hop, jazz, Irish step, African dance and classical Indian Kathak. “Everything in Larbi’s dance is unique,” says Osipova, who became entranced with his work at Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London, where the choreographer has been an associate artist since 2008. “He represents such a multicultural aspect of contemporary dance and movement.”

“It’s so wonderful to get their trust, that they’re so experimental to throw themselves into the hands of a contemporary choreographer,” says Cherkaoui by phone. “It’s very daring, a very cool thing to do as ballet dancers.”

Have ‘Mercy’

For the Russians, Cherkaoui combined two pas de deux that he had created on Les Ballets de Monte Carlo to create “Mercy,” a 15-minute study of human interconnectedness. “I’ve always pushed myself to see how one movement flows into the next one,” says Cherkaoui. “Mercy” begins on a harsh staccato tone and melts into legato.

“The relationship between the man and woman starts very violently, and then, by the woman forgiving the man, he learns to be more tender to the woman,” he adds. In the adagio-driven part of the duet, Osipova links her legs to her partner’s body, creating what Cherkaoui calls a “magnetic energy that brings power to transform the violence into tenderness.”

Cherkaoui rehearsed with two dancers from the Monte Carlo troupe, Gioia Masala and Rodolphe Lucas, who in turn have set “Mercy” on Osipova and Vasiliev at the Segerstrom Center. The pas de deux, set to sacral music by Baroque composers Heinrich Schütz and Johann Hermann Schein, will be accompanied live by L’Ensemble Akadêmia from Épernay, France.

Osipova also chose Pita to create a narrative work, “Facada,” for “Solo for Two.” “Since I am in London I’ve seen a lot of new choreographers, and Arthur for me was like new meal,” she says.

While working with the dancers at the Segerstrom Center, Pita found their approaches quite different. “Ivan has natural instincts to come up with ideas,” says Pita by phone. “He’s a lot of fun, extremely energetic and has a wonderful sense of humor, as does Natasha. She loves to pay attention to detail, getting as much information as she can to grab onto. You can see her brain processing everything that’s happening and how she’s working out what she wants to do.”

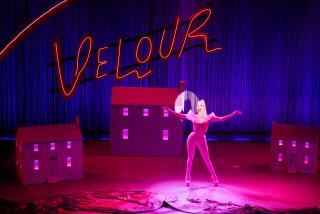

“Facada” shifts the program’s focus dramatically to a story about a Portuguese bride and her wedlock-conflicted groom. In Portuguese, “facada” literally means “to stab” and, in passionate vernacular, “a knife in the gut.” As the name implies, it also takes the couple into the realm of extreme marital discord. “‘Facada’ has a Mediterranean temperature to it,” says Pita.

Pita thinks of “Facada” as a possible back story to the icy Myrtha, queen of the wilis, the ghosts of heartbroken, affianced women who die before their wedding day, in the romantic ballet “Giselle,” one of Osipova’s signature roles. “Giselle might forgive, but Myrtha certainly does not,” says Pita. “This excites me.”

In the rehearsal process, Pita saw the dancers revealing some of their own traits in the characters, such as Vasiliev’s “wild child, free spirit” personality, while Osipova, he says, “is accenting things with her sense of humor. She’s quite funny, quite an eccentric personality, and that’s coming out.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.