Small-town cinemas want new films sooner

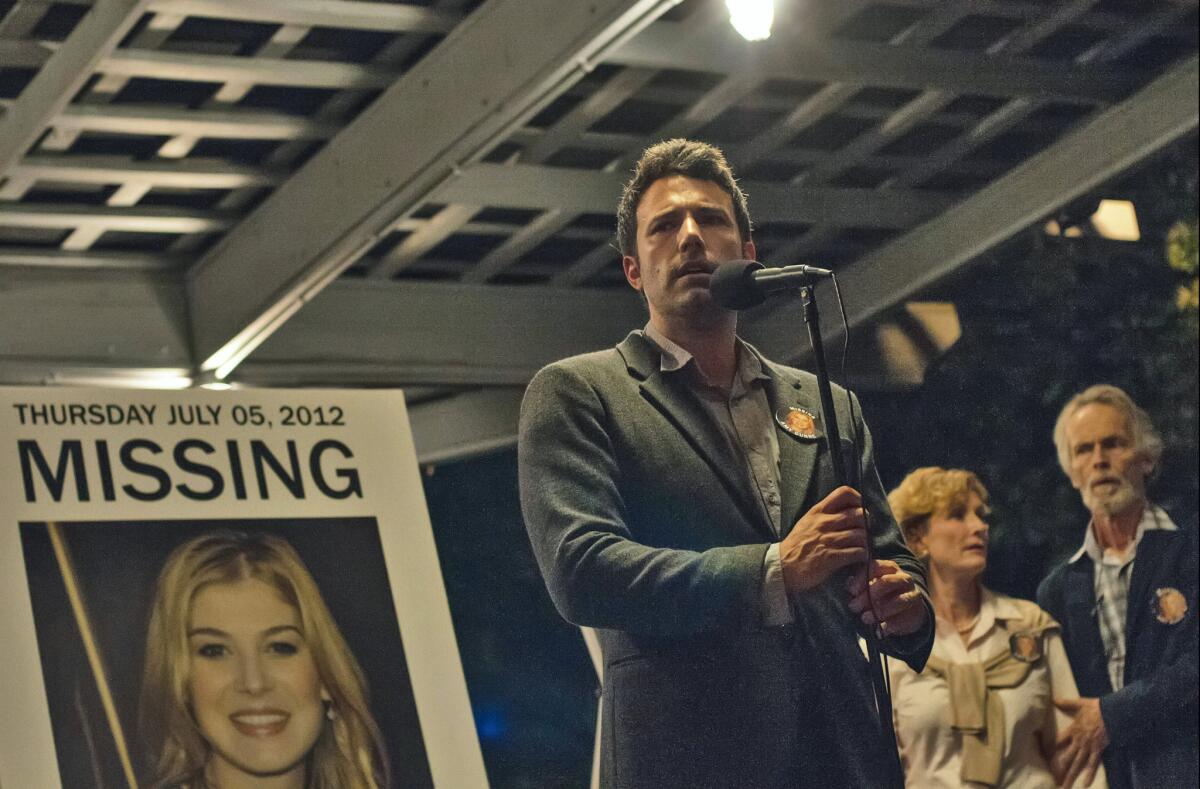

When the critically acclaimed David Fincher thriller “Gone Girl” debuted at the multiplex this month, Byron Berkley wanted to play the movie in all four of the small-town theaters he runs in east Texas.

But 20th Century Fox made the film available to only one of his venues in Kilgore, an oil-rich town with a population of less than 15,000. The others would have to wait another week after the Ben Affleck film screened in major markets across the country.

By then it was too late.

“In a world of instant gratification, it’s old news after two or three weeks,” Berkley said. “Some people say, ‘To heck with it, we’re not going to movies anymore.’”

Delays in showing new movies is a growing source of frustration for small-town cinema owners like Berkley, who complains that studios are relying on an outmoded distribution model that favors big-city multiplexes.

A group of independent theaters owners and members of the National Assn. of Theatre Owners recently aired their concerns in a series of discussions with studio executives in Hollywood, according to people who attended the meetings.

The sessions with studio distribution executives were said to be cordial, but executives who attended the meetings disputed claims they are squeezing out small-town theaters. The executives note that several variables determine when and where a film gets played, including the type of film, time of year and profitability of the auditorium.

“We’ve had a very good relationship with small exhibitors because we believe in their business,” said Chris Aronson, president of domestic distribution for 20th Century Fox, who met with some theater owners this month. “The bottom line is we’re running a business, and we license our films on a picture by picture basis.... We don’t want to be in a situation where our costs exceed our revenue.”

As for “Gone Girl,” Aronson said the studio had good reason to be cautious about releasing the movie in too many theaters given its mature content.

“R-rated movies in small towns don’t always go together,” Aronson said.

Friction over the issue of when theaters get to play movies has been magnified by a decline in ticket sales in the U.S. After a crop of weak movies, the industry is coming off its worst summer in ticket sales since 1997, when adjusted for inflation.

The slowdown comes after a period of heavy investment by cinema owners to convert their theaters to digital technology. With financial backing from studios, theaters are still paying off debts to buy digital projectors that cost $50,000 to $75,000 each.

Additionally, theaters are grappling with growing competition from entertainment options in the home and changing habits among consumers, who expect to see movies when they are released. That makes delays getting films on the big screen all the more costly to theaters forced to wait their turn to show the latest Hollywood fare.

“What has happened is that when a picture is released and has the potential to do some business and we would like to play it, the studio has decided they don’t want to let us play it and we have to scramble to find something to put on our screen,” Berkley said. “We’re trying to convince them you’re not doing yourselves any good. You’re hurting us and you’re hurting yourselves.”

Berkley said his theaters couldn’t book the Nicolas Cage movie “Left Behind” in its opening week Oct. 3, even though many of his customers wanted to see it.

“We had a lot of inquiries from our customers who just wanted to know when we were going to have it,” he said.

Dan Fellman, president of domestic distribution for Warner Bros. Pictures, said each movie has its own marketing strategy and often benefits from being phased into theaters.

“Word of mouth can be a very powerful thing,” he said. “When you have a movie that turns out to be No. 1 and you’ve got more people talking about it, it’s a good idea to come out in a second wave.”

Fellman added that some theaters simply don’t generate enough ticket sales to justify getting movies as soon as they are released.

In fact, studios and theaters have followed a similar distribution pattern for decades. Wide-release movies are first shown in major cities, then in mid-level markets, and finally in smaller towns and so-called second-run theaters several weeks after the initial release date.

One of the rationales for the model was the high cost of delivering film prints. Until the advent of digital, it cost $1,000 to $3,000 to make and deliver a film print to theaters. Currently, it costs less than $100 to deliver a digital hard drive and even less for a movie delivered via satellite.

Studios, however, are still paying $700 to $800 in so-called virtual print fees to help theaters finance the new digital equipment. The fees are part of an agreement with theaters to ease the digital transition. Virtually all 40,000 movie screens in the U.S. have replaced film projectors with digital equipment.

With lower distribution costs, independent theater operators argue that there is less economic justification for spacing out the release of new movies.

“We know our towns, we know our small markets, and because the cost is so low now, give us a show to make some money,” said Joe Paletta, chief executive of Atlanta-based Spotlight Theatres, which operates four theaters in Georgia, Pennsylvania and Connecticut.

“Our clients are pretty astute,” he added. “They are very aware of what movies are released and when, and they have short attention spans when it comes to seeing new releases.”

Follow me Twitter: @rverrier

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.