Television works to aim a little higher in representing the modern male

It’s kind of the #MeToo generation’s version of “My dog ate my homework.” When predatory men have been confronted with their past mistreatment of women, their go-to excuse often tends to be, “But I didn’t know any better. That’s what I grew up with.” Instead of introspection, they blame popular culture for their belief that sexual harassment was somehow socially acceptable.

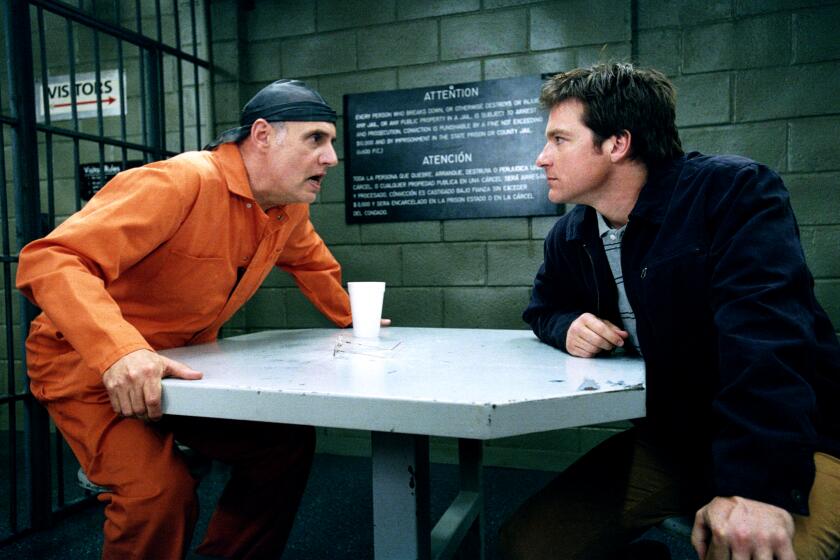

To be sure, television hasn’t been entirely innocent in all this, for decades offering up such male nonrole models as Ralph Kramden, Al Bundy and Charlie Harper. For every Andy Taylor, Hawkeye Pierce or Steven Keaton, TV history has served up a clueless dude who more often than not treated women with all the tenderness and understanding of a Benny Hill sketch.

“There is this history, especially in sitcoms, of this not great, archaic, very hetero-normative idea of what a man is,” says Jen Statsky, supervising producer for NBC’s “The Good Place.” “There have been so many jokes about the value of a man being measured in how many women he’s slept with, and how embarrassed he is if it isn’t many.”

Adds Terry Crews, who plays devoted husband and father Terry Jeffords on NBC’s “Brooklyn Nine-Nine”: “TV needs to just concede we messed up and didn’t do it right. Years and years of bad messages have been sent. I remember watching ‘Married with Children,’ which was a brilliant example of not only toxic masculinity but also toxic family. That was all supposed to be part of the joke. Now, I have a feeling people wonder, ‘I laughed at that?’”

These days, whether it’s because of the #MeToo message or writers are just aiming a little higher, television is serving up more examples than ever of a new, necessary breed of sensitive guy. From the anxious but well-intentioned Chidi on “The Good Place” to the impossibly chivalrous Jamie Fraser on Starz’s “Outlander,” to pretty much any male lead on NBC’s “This Is Us” or ABC’s new show “A Million Little Things,” there’s clearly a trend toward creating guys who are more likely to boast about their feelings than about whom they slept with last night.

It’s not that there’s anything inherently wrong with the Al Bundys of the world. The character was “a hell of a funny guy,” believes Jaime Camil, who plays the self-absorbed but ultimately genuine Rogelio De La Vega on the CW’s “Jane the Virgin.” “But at the same time, what’s happened to men is it seems like you’re not tough if you show feelings and emotions. If you show love to your kids, you’re portrayed as not being real men. Not everything has to be a PBS show, but I think there’s a way to show how respectful men should behave without losing comedy. These concepts don’t have to fight with each other.”

In other words, what’s happening is not so much a replacement of clueless men but more an expansive view of what it means to be a man in this day and age.

“It’s about representation,” says Statsky. “What’s interesting right now is we’re seeing a lot of different types of men as well as women. It’s OK to have an Al Bundy character, but the problem is for so long, the only male characters people saw were not super-sensitive but were very alpha male. There were a lot of slobs with the hot wives. It was so much of the same thing for so long. But now, it’s nice to see something new and different, something reflective of what we’re experiencing in culture at the same time.”

Today’s TV men are certainly far from perfect when it comes to their on-screen relationships, nor should they be, adds “Grey’s Anatomy” showrunner Krista Vernoff. She sees it as a “dangerous conversation” when the discussion turns to wanting all male characters “to be sensitive and that the others are somehow problematic.” They can all have flaws, but they should pay a price for them rather than have them simply be a punchline that’s quickly dismissed the following week.

“I loved ‘Breaking Bad,’ and Walter White did some horrific things,” she says. “But we always felt the ramifications of those decisions both on him and on the people who surrounded him. The violence was never inconsequential.”

The point with this new breed of television male, according to “A Million Little Things” creator and executive producer DJ Nash, isn’t to hammer audiences with guys who are too good to be true. Rather, it’s to show that “men are vulnerable. That was something I wanted to make sure I worked on when designing the show. I wanted everyone to be broken in a different way.”

Because his series centers on a trio of male friends experiencing various midlife crises, networks were wary that such self-reflection might be too much for either gender to watch. Women wouldn’t want to see men complain about their problems while men wouldn’t want to see guys exposing what they really think and feel. However, when ABC showed it to test audiences, “not one woman tuned out,” according to Nash. “They liked getting a look into the side of men they’re not normally privy to. And I think guys appreciate that we explore the pressures that the men in the show put on themselves.”

Which, he hopes, might make male viewers a bit more introspective about their own relationships. That’s why this more complex, realistic breed of men we’re beginning to see may be TV’s make-good following all those years of trafficking in the same old stereotypes. And perhaps eventually, says Crews, assist the cultural shift that’s come with the #MeToo movement.

“With creating entertainment comes a responsibility to do things right,” he says. “Art doesn’t solve problems, but it can highlight and clarify them and help us focus on certain things that we can then understand and make a move to solve.”

Television may not have encouraged all the massive male misbehaviors that continue to come to light, but thanks to sensitive guys like Terry Jeffords, Chidi Anagonye and Jack Pearson, it is at least helping to further the conversation about them.

“It does matter that these characters we create are blasted into people’s homes every week,” says Statsky. “People do internalize them and start to think, ‘Oh, this is the way men and women behave.’ As a show creator, you do have a say in what messages people receive and for too long, some characters weren’t really serving people and might actually have been harming them. It’s been a disservice to men to keep some of those old stereotypes alive. I want to show men as good, kind, sensitive people and a reflection of guys that I know and have spent time with.”

WATCH: Video Q&A’s from this season’s hottest contenders »

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.