As Walton Goggins filmed ‘Hateful Eight,’ he heard the film echoing the news

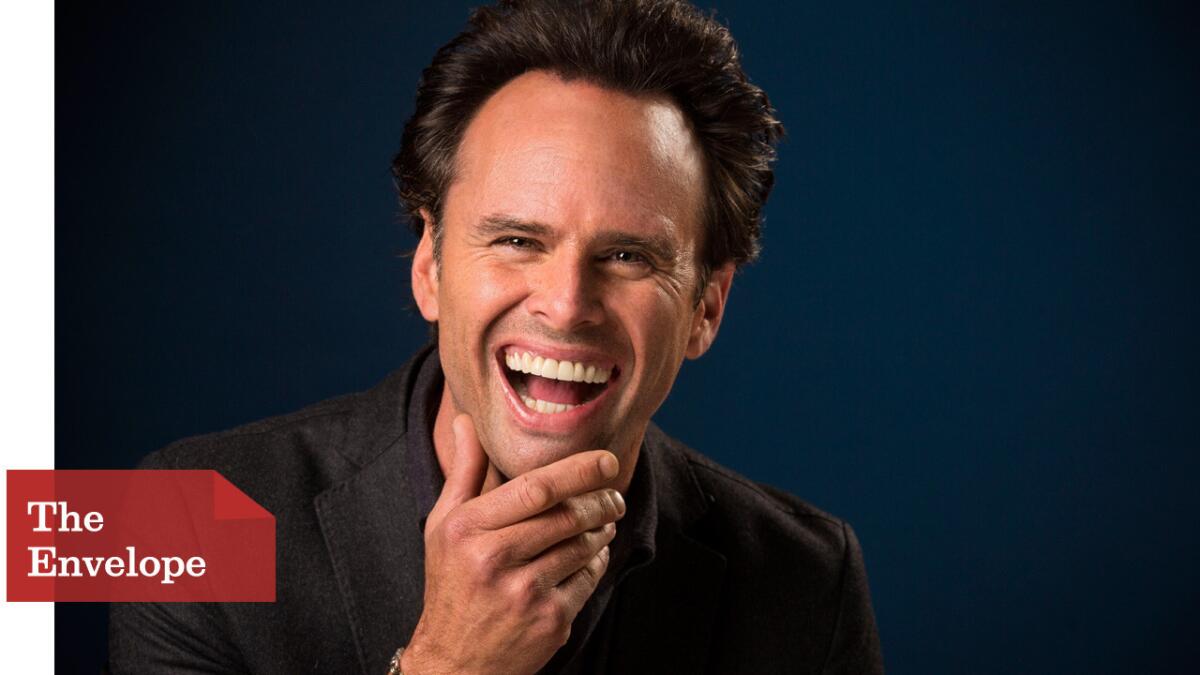

Walton Goggins can hardly contain himself as he recalls filming Quentin Tarantino’s verbose, three-hour western “The Hateful Eight.” Inside a quiet hotel suite overlooking Beverly Hills, Goggins radiates intensity, standing up at one point to reenact a memory from the “once-in-a-lifetime experience.” Considering his exhaustive calendar — working 80-hour weeks for the better part of 14 months — his enthusiasm is all the more impressive.

For years now, Goggins has split his time between two FX dramas. He’s played transgender prostitute Venus Van Dam on “Sons of Anarchy” and the complex reformed bank robber Boyd Crowder on “Justified,” a role that earned him an Emmy nod. Next year, he’ll costar with Danny McBride in the HBO comedy series “Vice Principals.”

SIGN UP for the free Indie Focus movies newsletter >>

As Goggins tells it, he first caught Tarantino’s eye as the bumbling Det. Shane Vendrell on the “The Shield.” Not long after, the director cast him in “Django Unchained” as slave fight trainer Billy Crash.

This time around, Tarantino put Goggins front and center as racist sheriff Chris Mannix. It was a rigorous experience, the actor tells The Envelope, and not just because the stellar ensemble — which includes Bruce Dern, Samuel L. Jackson, Kurt Russell and Jennifer Jason Leigh — spent most of the five-month shoot together on a soundstage kept at a blizzard-friendly 29 degrees.

This film unfolds a lot like a stage play. What was it like on that set?

That really was the feeling. We were in this room for so long. And it was so cold but it was so warm with communion that, after Quentin had gotten a shot he wanted, there was this feeling like a ‘50s green room at the Beverly Hills Hotel. We would talk. And Quentin would talk about movies with Bruce, and Kurt would throw his stories in there. And I would just try to make people laugh and Sam had all his stories. And all around you, the set was being moved. Music was being played. It was like we were doing a play for ourselves.

It definitely comes across that you’re enjoying yourselves.

Before the [production] started I went seven movies in seven days. A Quentin Tarantino marathon. I really tried to digest them. “Kill Bill” was a particularly long day — and a long digestion afterward. But you realize that Quentin has written so many incredibly dynamic characters over the course of his career that don’t often get the opportunity to interact with all the other dynamic characters he’s created. This was a very unique opportunity for this troupe of actors to witness one another’s work and to get to interface on a daily basis on camera. ... We still text almost 30 times a day.

Let’s talk about your dynamic with Samuel Jackson.

That’s very personal to me in the sense that I have been given an opportunity by Sam to move beyond my idolatry of the man and move into the space of vulnerability that’s required of a friendship. And to participate in the healing of race relations [within the film] in that way, it’s unbelievable. Most people, when you say the things that Chris Mannix says, you don’t come back from that. And you are perceived this way and you’re sent off the reservation. You’re a pariah by 21st century standards. But to be able to take it from that extreme to where this movie ultimately ends, that’s a walk that very few actors are afforded an opportunity to do.

Coming from the South, what do you think Quentin’s last two films bring to the conversation of race relations?

I don’t know that a man, who is as poetically loquacious as Quentin is, could make more clear how he feels about the state of the world than he can through the visual imagery of this film. And there are multiple moving metaphors throughout. For me, it was an opportunity to understand when it comes to winning hearts and minds that you don’t do that a nation at a time. You do that one person at a time. After we did the stage reading and started rehearsals, all of this started happening in the African American community. Over the course of making this movie there were two articles that had headlines that were paraphrasing lines Quentin had written in this movie. One in particular was almost verbatim. At times it felt like, is life imitating art? Or are we imitating life? It was as if these two rivers were destined to meet.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.