At Cannes, real-world events take stage

CANNES, France — Simav Bedirxan chokes up when she recalls watching images of the children she once taught. “In the video they’re so alive, still dancing and playing,” the soft-spoken woman said as she sat in an apartment in this coastal Riviera town, barely getting the words out between tears. “But they’re all gone now.”

A Kurdish schoolteacher from Homs, Bedirxan, 35, is co-director of “Silvered Water,” a new impressionistic documentary about the Syrian war and its many victims. In the film she and veteran Syrian filmmaker Ossama Mohammed (“The Box of Life”) engage in lyrical dialogue over more than 1,000 gripping images of the conflict, filmed by them and many ordinary citizens. The movie had a special screening recently at the Cannes Film Festival.

Also in the official selection this year is “Maidan,” a documentary about the Ukrainian uprisings shot as recently as March, while more traditional dramas from Russia and Turkey attempt to show those countries’ complicated new realities.

The French confab that ends Sunday is best known for celebrity glitz and high-end dramas. But as crises in several parts of the world have mushroomed and as improvements in technology have allowed for movies to be shot and edited ever more quickly, Cannes has taken on a somewhat unlikely role: as a venue for charged, newsy stories, the film festival as political sanctuary. In a sense these movies mark a return to Cannes’ ideological roots and also offer the kind of political edge to the everyday that the French tend to esteem.

Bedirxan and Mohammed last weekend held a touching ceremony in which they tagged the upscale Boulevard de la Croisette with graffiti commemorating Syrian war victims. And the recent imprisonment by Russian authorities of Oleg Sentsov, a Ukrainian filmmaker living in Crimea, on terrorist charges sparked calls for his release at a press conference at the Ukrainian Pavilion at the festival.

“Cannes is a place that will have you when others won’t,” Mohammed said. “It’s a different idea of cinema, maybe a more important one.”

Mohammed has firsthand experience. In 2011, he flew here to speak on a panel about the burgeoning Syrian conflict. To a question about the state of affairs under President Bashir Assad, he questioned the regime’s holding of political prisoners. The massive media coverage of the festival combined with the exponential effect of social media helped the comments quickly reach his home country, prompting death threats. He fled to Paris and has lived there ever since.

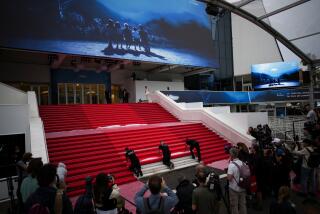

A somewhat similar dynamic was in play this year with the Iranian actress Leila Hatami, a member of the prestigious nine-member competition jury. Cannes protocol has many female jury members and filmmakers greeting festival director Thierry Fremaux at the top of red-carpeted stairs with a customary two-cheek peck. Few thought anything of it when Hatami, dressed in traditional garb, did just that before a premiere last week. But the image quickly reached authorities in Iran, and deputy culture minister Hossein Noushabadi rebuked her on a state news-service site for projecting a “bad image of Iranian women.”

On Wednesday, a kind of vicarious protest took place at an official screening when Ukraine’s Sergi Loznitsa, a respected narrative filmmaker behind such movies as “My Joy” and “In the Fog” presented “Maidan,” an observational documentary he shot over three months in Kiev’s eponymous square beginning in December.

The movie tracks the period that saw hundreds of thousands of citizens take to the streets to protest the government of then-President Alexander Yanukovych. Unlike hand-held pieces that have emerged from similar hot spots, such as Egyptian Oscar nominee “The Square,” “Maidan” uses static shots and long takes to capture tableaux of everyday Ukrainians participating in the political process. As the voices of chanters and speakers ring in the background, Loznitsa holds the shot for minutes at a time so viewers can feel like an intimate part of the protests as well as scan the busy frame, where they can pick up details such as individual facial expressions.

Though devoid of interviews and other documentary conventions, the movie has an unexpected kind of flow, as viewers see the sunniness of early protests fade into the violence of a crackdown and, eventually, the successful if costly removal of a corrupt leader. “I wanted to show the world the people who sacrificed their life for democracy,” said Loznitsa over coffee at the Majestic Hotel. “And I wanted to do it in the most artistic way possible. Films about protests can be beautiful tapestries too.”

He then implored those seeing the movie to pray for Sentsov, who is being held in a Moscow jail.

At the movie’s debut Wednesday night, Loznitsa made an explicit connection between the setting and the events of his film. “It’s a great place to make a premiere of this film, in a country of a great revolution,” he said.

Loznitsa next aims to bring his movie to the fifth-annual Odessa Film Festival in July. The gathering in the troubled region will go on, the festival’s director, Julie Sinkevych, said, noting she had been spending her days at Cannes trying to raise money from other countries’ festivals and film boards to fill a gap left by departed sponsors.

Though grainier and more handmade (a continent apart, the directors solicited images from citizens and edited the film online), “Silvered Water” contains similarly compelling images. In one shot a soldier shows his military ID and goes on to say how he was recruited to violently break up a peaceful demonstration; in another a slain father and child, unarmed, lie on the ground in a pool of blood. In a film-festival culture in which even the grittiest dramas prefer stylization and other distancing effects, the images are jolting.

In some ways the move to politics harks back to Cannes’ earlier years — the festival was started in 1946 as Europe sought to recover from World War II and in the 1960s became a flash point for political unrest; in 1968 Jean-Luc Godard and Claude Lelouche famously halted the festival midway through in solidarity with student protests.

But with the rise of celebrity culture, the festival in recent decades has become a less fraught affair, as likely to make headlines for an Angelina Jolie red-carpet moment than an act of social consciousness.

Of course, politics need not be overt. In Nure Bilge Ceylan’s Turkey-set “Winter Sleep,” the director takes an epic-length look at competing ideologies and class tensions in a small town in Cappadocia. “You can say a lot with an ordinary story,” Ceylan said of the movie about his country, which has been riven by economic and religious tension in the past few years. He added, “Journalism tells you about the situation of a country. Art can tell you about the lives of the people in it.”

And in Andrei Zyvagintsev’s Russian competition film “Leviathan,” a mayor pushing a man off his property becomes a metaphor for the abuse of power by Russian oligarchs. (Don’t be surprised if several of these films end up with art house distributors in the U.S., though the more likely venue for stateside viewing will be at film festivals.)

For all the potency of these films, there’s a quiet acknowledgment of the futility of art in the face of military might and other forces beyond filmmakers’ control.

In “Silvered Water” Mohammed says that “for the regime, the camera is a weapon,” but watching the brutalities in his film, one sometimes infers the opposite message. No matter how powerful the image, it is no match for helicopters with guns.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.