Univision’s Jorge Ramos a powerful voice on the immigration front

Univision’s popular news anchor has a deeply personal take on immigration reform, an issue that’s long been his top story.

Jorge Ramos' march for immigrants began 30 years ago when, clutching his guitar and a student visa, he took a nervous walk through Los Angeles International Airport.

He had just quit his first reporting job after his bosses at a Mexico City TV station demanded he soften a segment critical of Mexico's government. Ramos had refused.

He sold his Volkswagen Beetle and used the money to buy a plane ticket to Los Angeles and enroll in UCLA Extension journalism classes. Within months, the 25-year-old had landed an on-air job with Los Angeles' Spanish-language station KMEX-TV, then a shoestring operation in a run-down house on Melrose Avenue.

"To me it was a palace," he recalled. "The United States gave me opportunities that my country of origin could not: freedom of the press and complete freedom of expression."

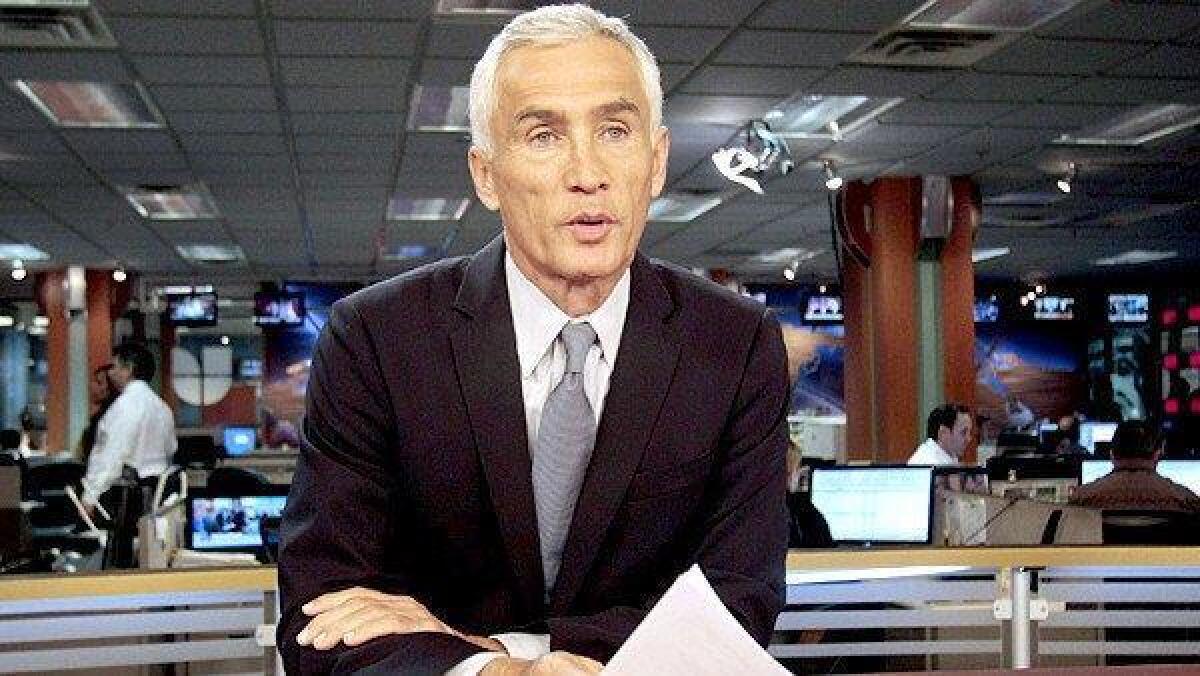

Today Ramos anchors the evening news with Maria Elena Salinas at Univision, the fifth-largest TV network in the U.S. More than 2 million viewers tune in to "Noticiero Univision," Spanish-language TV's No. 1-ranked newscast.

That's three times the audience of CNN's "The Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer."

On Sunday mornings Ramos interviews newsmakers on his political affairs show, "Al Punto," which recently grabbed headlines after New Jersey Sen. Robert Menendez said the Senate lacked the votes to pass a bipartisan immigration reform bill.

A fixture behind Univision's anchor desk for 26 years, the silver-haired, blue-eyed Ramos has been called the Spanish-language Walter Cronkite, a trusted source of news. But he is more than that for his viewers, including some of the 11 million immigrants who have entered the U.S. illegally or overstayed their visas."

"Spanish-language news has almost the same pull as the priest in the pulpit," said Congressman Xavier Becerra, a Democrat from Los Angeles. "And Jorge Ramos is the pope, he's the big kahuna."

President Barack Obama talks with Univision's Jorge Ramos in the Roosevelt Room of the White House. (The White House) More photos

He is also an unapologetic proponent for immigration reform.

Long before the current debate over immigration policy in Washington, Ramos was on a crusade to demand changes in the law by chronicling stories of broken dreams and broken families.

Last fall, when no Latinos were chosen to moderate any of the presidential debates, Ramos complained that the debate commission was "stuck in the 1950s" and then made news when Univision held its own candidate forums with Mitt Romney and President Obama. Ramos didn't go easy on either one.

He sparred with Romney over the Republican candidate's proposed "self-deportation" policy, which Ramos considered an insult to Latinos. Later, he confronted Obama for the deportation of more than 1.4 million people, and for reneging on his promise to tackle immigration during his first term.

"A promise is a promise. And, in all due respect, you didn't keep that promise," Ramos told an uncomfortable-looking Obama.

English-language networks played the clip on their own programs; Ramos made sure of that. He switched to English from Spanish when confronting the president.

Our position is clearly pro-Latino or pro-immigrant ... We are simply being the voice of those who don't have a voice."— Jorge Ramos

"I didn't want the words to be lost in translation," Ramos said during a recent interview at Univision's Miami headquarters. "I wanted him to know how important immigration was for us."

A year ago Washington Monthly magazine called Ramos the broadcaster who would most determine the 2012 election. His increased stature has led some to question Ramos' advocacy approach.

"We do have this antique notion that a newsman will be disinterested and stay above the fray but Ramos reports like he is a lobbyist for the National Council of La Raza or a Democratic pundit," said Tim Graham, director of media analysis for the conservative watchdog group, Media Research Center.

Ramos makes no apologies for his or Univision's forceful stance.

"Our position is clearly pro-Latino or pro-immigrant," he said. "We are simply being the voice of those who don't have a voice."

Supporters say Ramos is continuing a long tradition in ethnic media of fighting to correct social unfairness.

Federico Subervi, a communications professor at Texas State University, pointed out that Univision's coverage is in sharp contrast with that of other networks and cable channels.

"Immigration is the top story on almost every newscast," Subervi said. "Most of the news on English-language television depicts Latinos as causing problems or the ones having problems. Spanish-language TV tells the stories of people trying to change policy: It is solution-oriented."

Ramos insists that journalism is his first priority. He complained to Obama's election team when his likeness was used in a campaign ad. He told his TV audience, "We have always defended our journalistic integrity." Still, he concedes that he is closer to the immigration story than most.

"I am emotionally linked to this issue," Ramos said. "Because once you are an immigrant, you never forget that you are one."

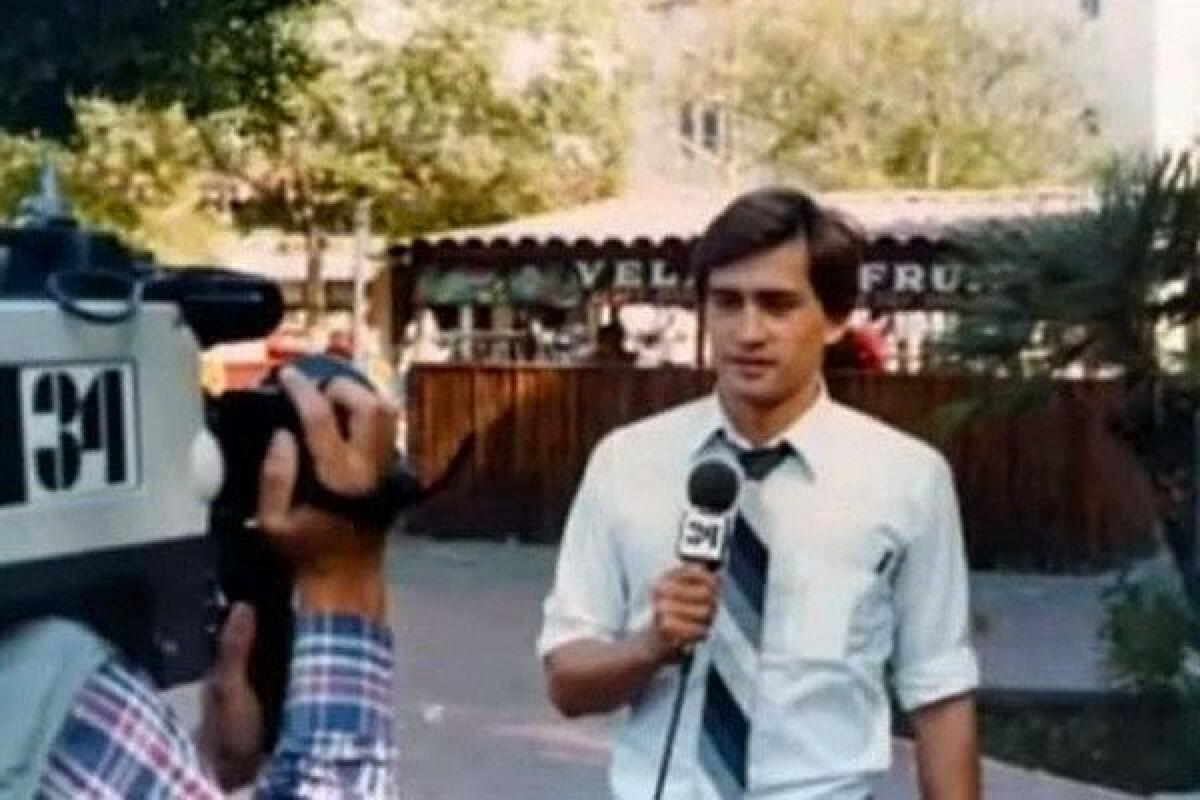

Jorge Ramos reports for KMEX in Los Angeles in 1984. (Univision) More photos

In Los Angeles during the mid-1980s, City Hall officials didn't take him and his KMEX cameraman seriously.

"No one would speak Spanish to us," Ramos recalled. "Some politicians dismissively would say: 'Well, my gardener speaks Spanish' or 'My driver speaks Spanish, but I don't.'"

He was shy and ill-prepared when he was tapped, at age 28, to be Univision's news anchor. He struggled to use the teleprompter, which often went on the fritz.

Things have changed. Days after the Los Angeles election, Mayor-elect Eric Garcetti granted his first national TV interview -- in Spanish -- to Ramos on "Al Punto."

Ramos now provides a steely cool presence on the air, and is known around Univision for his discipline.

A pull-up bar is mounted in the doorway to his sparsely furnished office. Younger colleagues groused when the trim, 55-year-old Ramos bested them by performing 17 pull-ups in an impromptu competition.

Spanish-language gossip sites were intrigued when the twice-divorced father of two began dating Venezuelan Chiquinquira "Chiqui" Delgado, host of Univision's dancing competition, "Mira Quien Baila." The couple is still together.

In addition to the two Univision news shows, and a third one being planned for an English-language cable news channel that Univision intends to launch with ABC News, Ramos writes a weekly column and is the author of 10 books -- the most recent is "A Country for All: An Immigrant Manifesto." A voracious reader, Ramos quotes Alexis de Tocqueville and the Declaration of Independence.

"What I find most interesting about the U.S. is this idea of equality," Ramos said one evening as he prepared to deliver the news, applying his own makeup by glancing at his reflection in a window. "That's what I'm trying to do with immigration. If what the founding fathers said is true, that we are all equal, then let's fight for that."

For Ramos, conflict is a central theme. He approaches his interviews with world leaders in the context of warfare. "My only weapon is the question," he said.

The cover of Jorge Ramos' book "La Ola Latina." (Handout) More photos

He also has demographics on his side. Latinos are a growing constituency -- 50 million strong in the U.S. -- with increasing political clout. Obama was reelected with 71% of the Latino vote.

Ramos is not discouraged that many in Washington seem unwilling to change immigration policy. "This is our best chance since 1986," he said, referring to that year's big immigration overhaul. "Politicians know there are consequences, and that Hispanics will always remember who voted for it and who voted against it."

Ramos said his most difficult decision was leaving behind his family and homeland "to come completely alone to the U.S." His father, who envisioned a career for his first-born as doctor, architect or engineer, did not support his son's decision to become a journalist.

"He said, 'What are you going to do with that?'" Ramos recalled. "I told him, 'You'll see.'"

In his father's final years in Mexico City, a satellite dish allowed him to watch his son's broadcasts from Miami. The two would talk on the phone each night. Now Ramos has thoughtful conversations with his own son. Nicolas, who turns 15 this month, was born in Miami, is fluent in English and doesn't watch much Spanish-language TV. He frequently corrects his father's English pronunciations.

Not long ago, Nicolas asked whether it was difficult to pose tough questions to leaders such as President Obama.

"I told him, 'Yes, it is,'" Ramos said. "But what is so great about this country is that you can do it and nothing happens to you. If I had stayed in Mexico, it would be a completely different story."

Yet it took many years for Ramos to become a U.S. citizen. Deeply conflicted, he had long considered himself just another "Mexican with a green card."

But five years ago, to mark his 50th birthday, Ramos took that step. He had lived in Mexico 25 years and 25 years in the U.S.

"You have to go through a mental and emotional process to recognize who you really are," Ramos said. "I finally recognized that I cannot be defined by one country. I am from both countries. It took me many years to make peace with that thought, and that I was never going back to Mexico."

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.