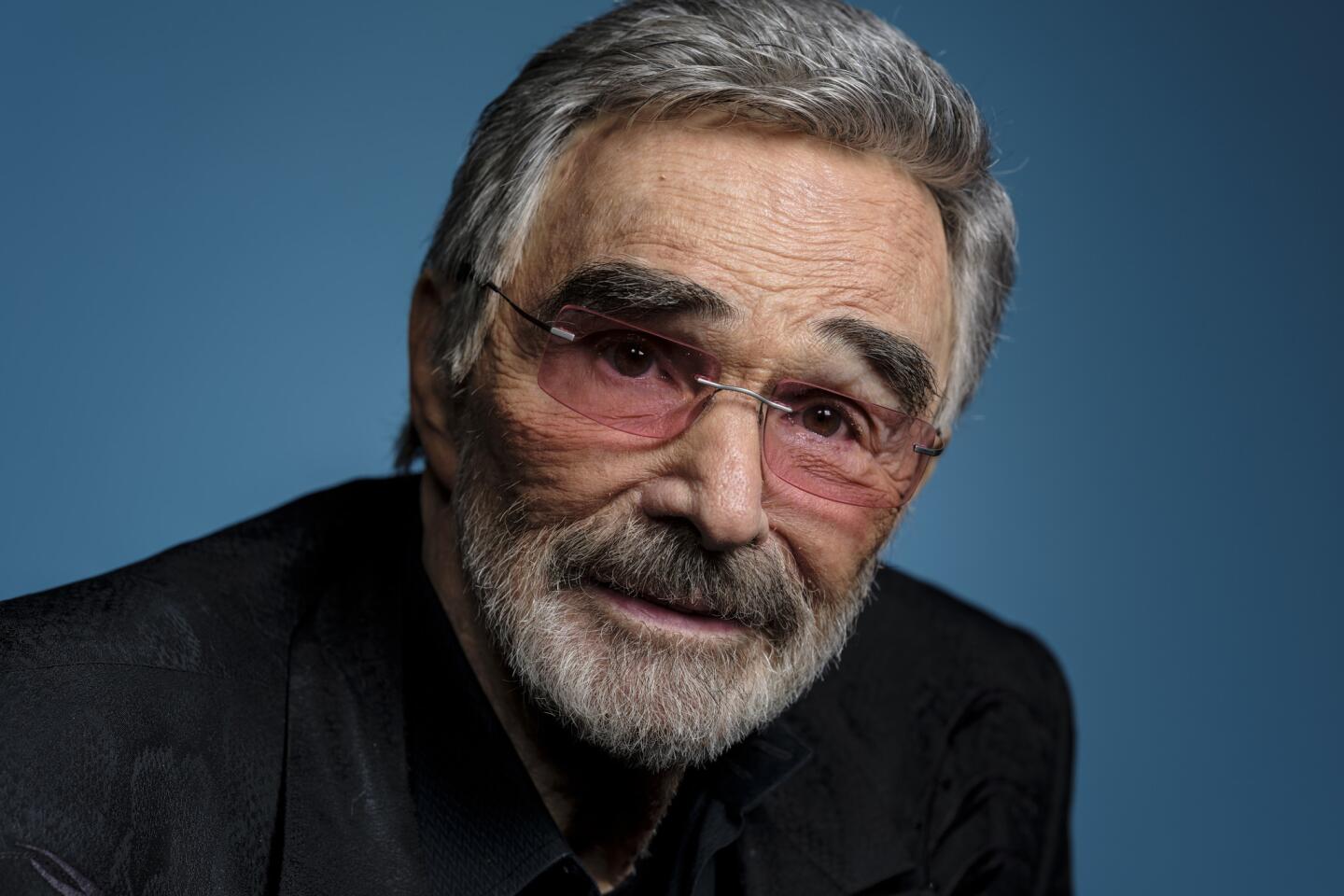

An Appreciation: Burt Reynolds ran through my youth as a charmer and a spinner of wiles

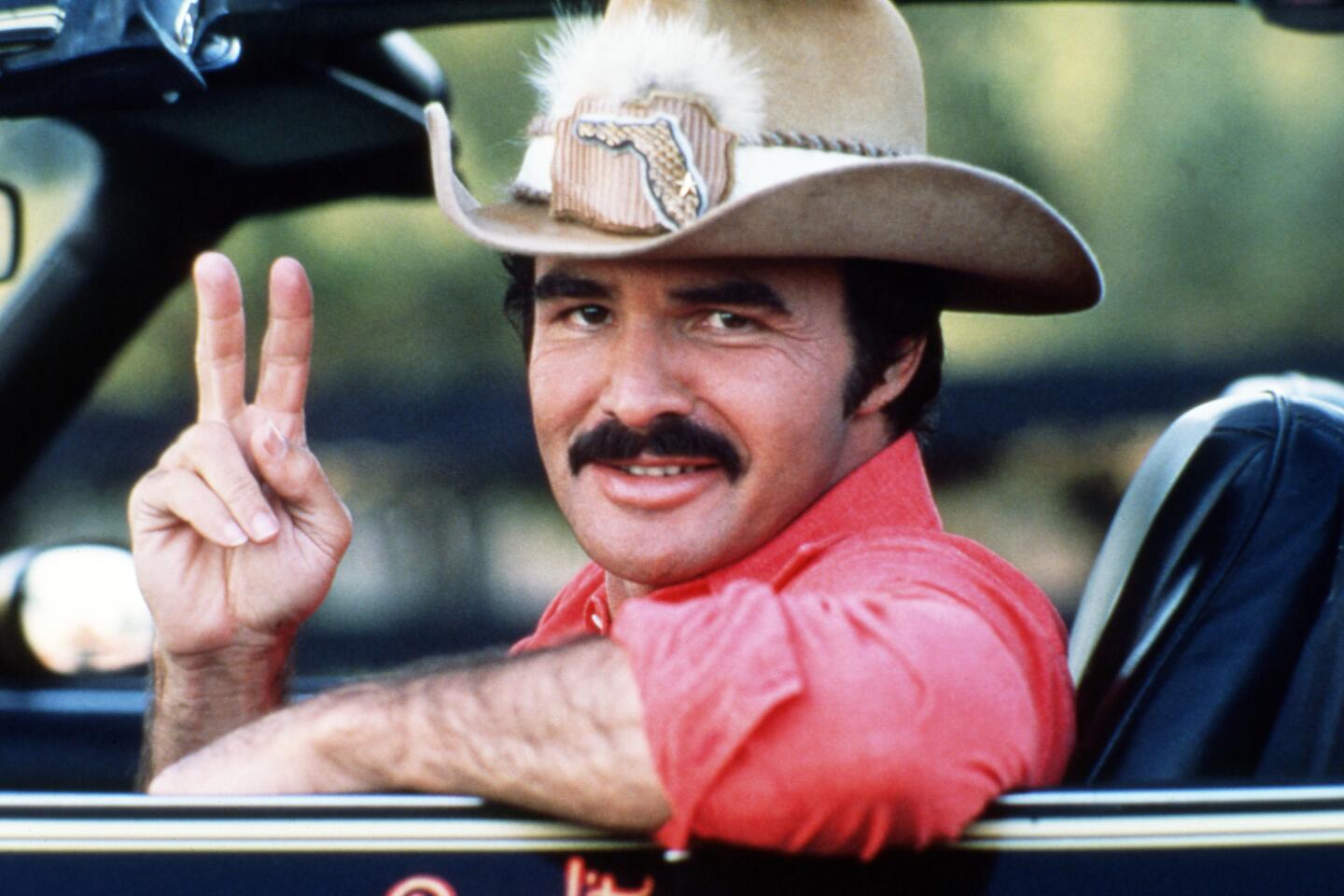

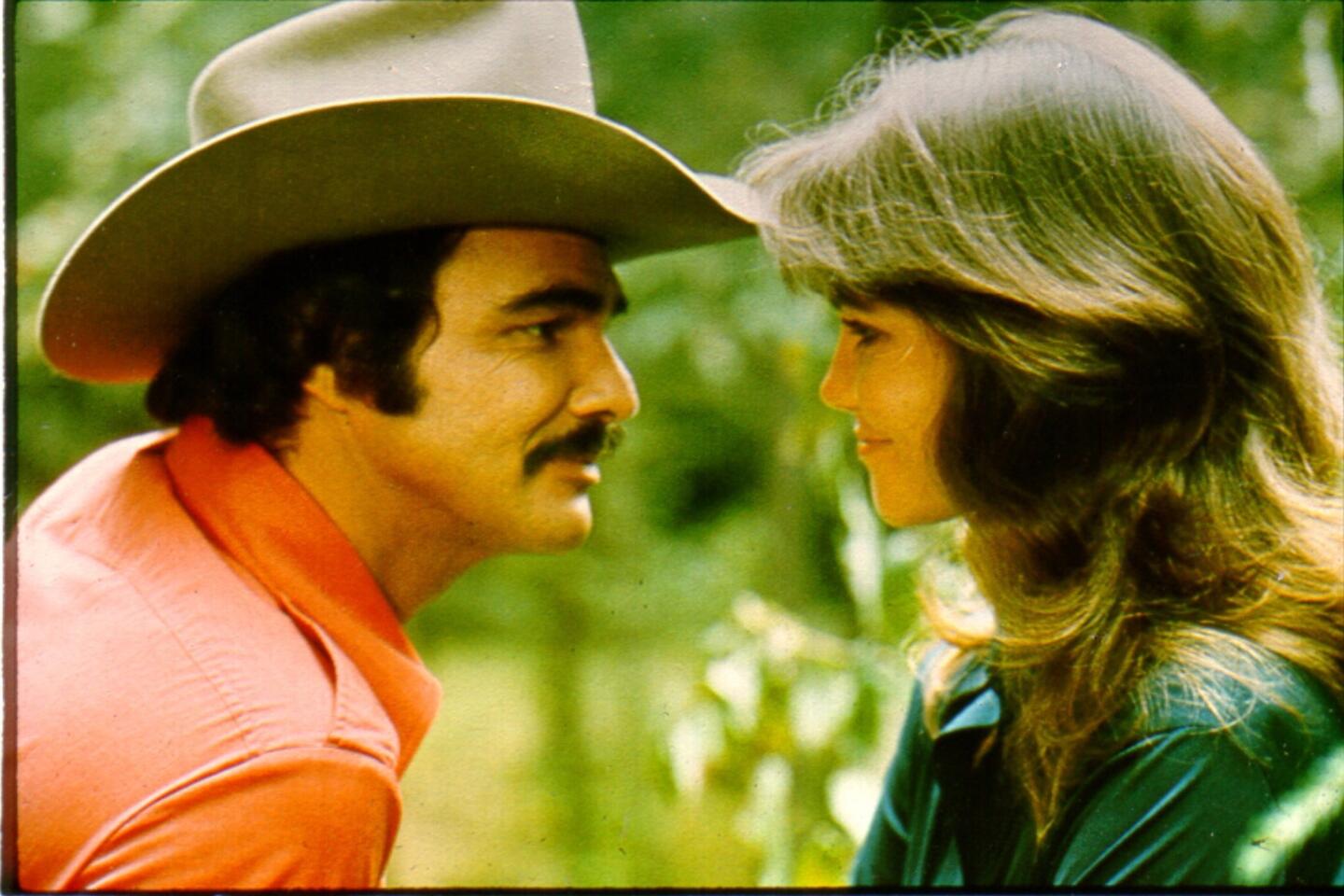

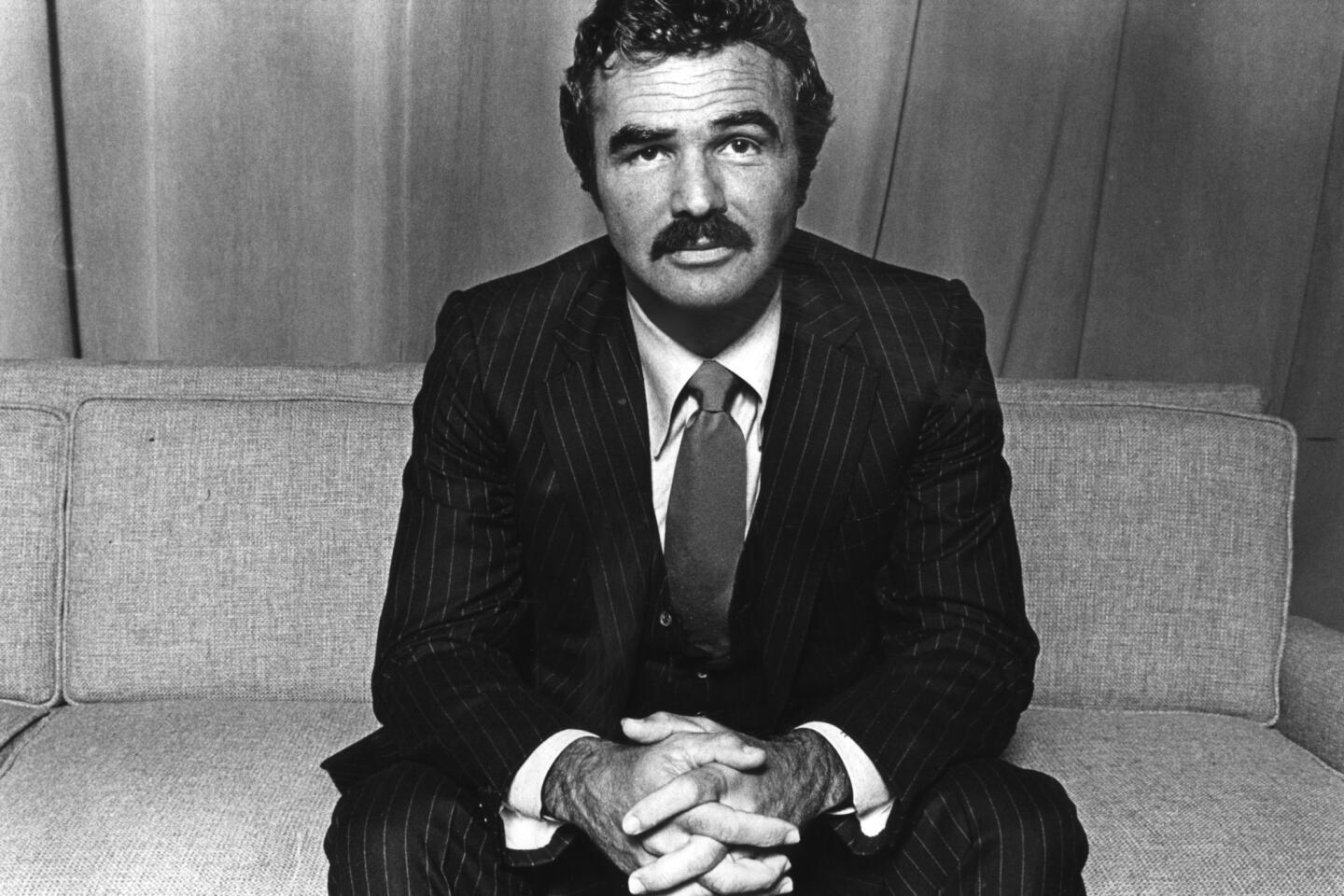

You had to like him, coming at you with a wink and a smile, as if he had swallowed all the world’s secrets. He was cool, slick, a few steps ahead of the cops, a wiseguy with a Texas hat and a mustache, who back in the day was a box office sure bet, a star who could draw in men and women in equal measure, but for different reasons.

Burt Reynolds was a charmer, a spinner of wiles and self-deprecating grace. He was the kind of guy you’d sit with in a roadhouse and watch unfold a map to all the places you’d never been. He knew his roots and revered his Florida upbringing; his drawl was as smooth as a snake sliding through the Everglades. His films such as “Smokey and the Bandit” were celebrations of the Southern everyman — the one often underestimated — who pulls a prank and escapes to glory.

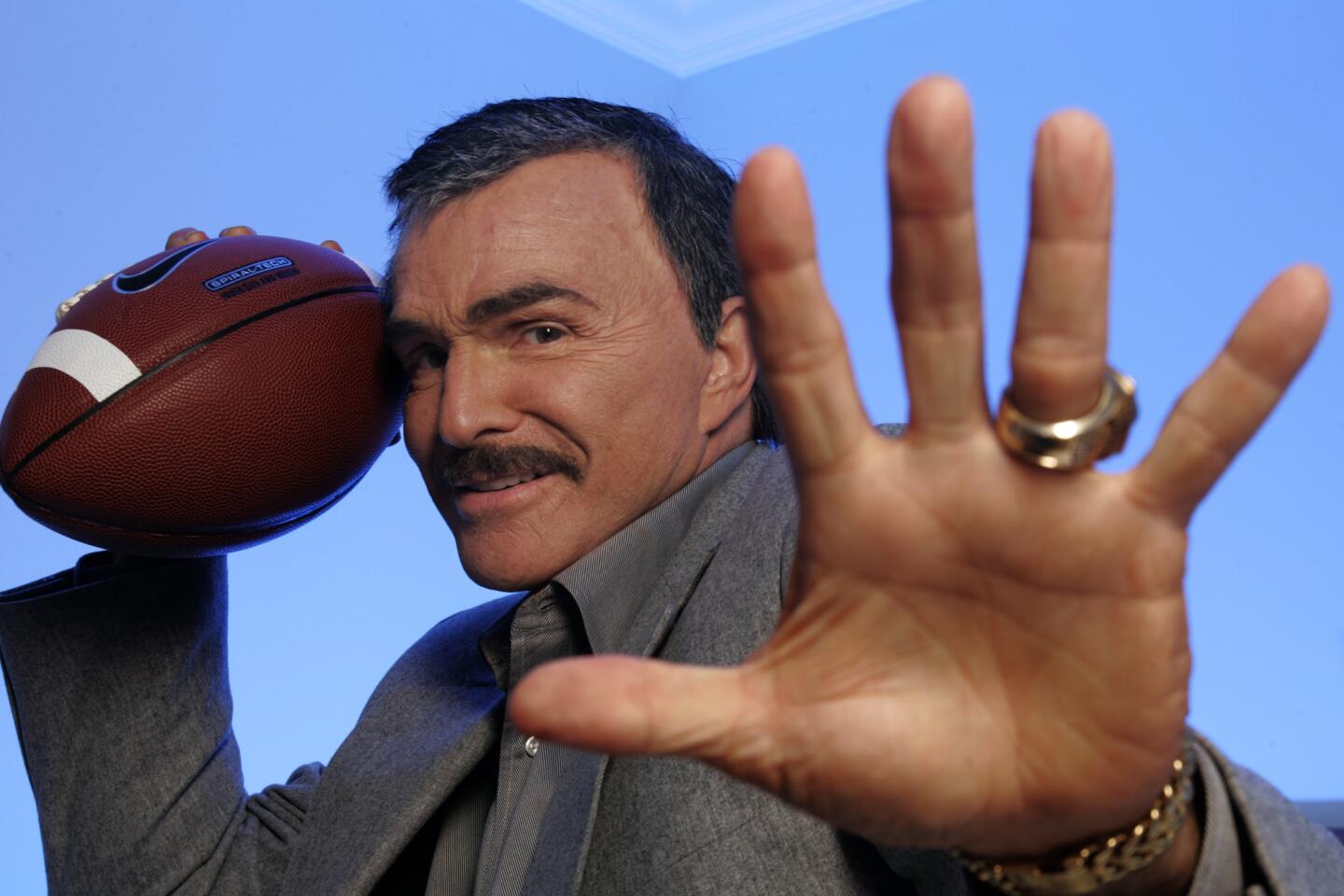

“Lots of movies ridiculed Southerners, and I resented them,” Reynolds wrote in his 2015 memoir, “But Enough About Me.” “I wanted to play a Southern hero, a guy who was proud of being from the South. . . Most of those folks are middle-of-the-road, not left or right. They believe in God, they work hard, and they love their country. They’re the people I grew up with, and I like them.”

RELATED: Burt Reynolds, wisecracking star of ‘Smokey and the Bandit’ and ‘Deliverance,’ dies at 82 »

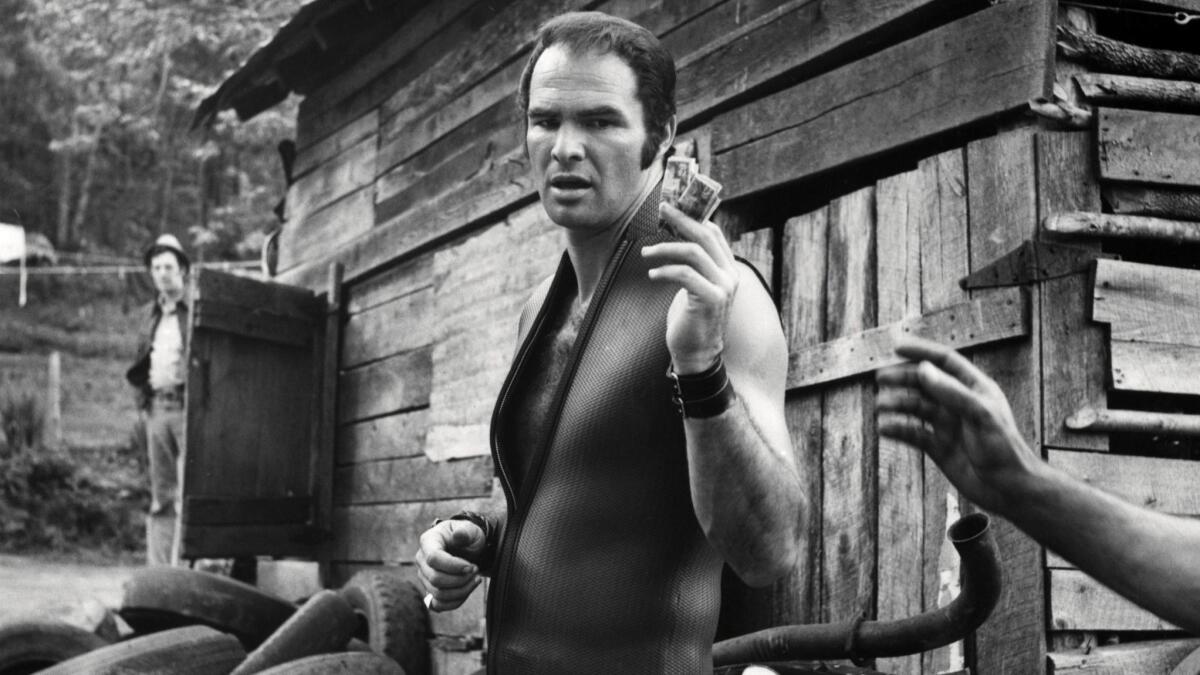

He’s gone, dead at 82. But he is forever part of my youth, a flickering piece of adolescence. His Lewis Medlock in “Deliverance” was a fierce survivor cut from the earth as if a character out of Hemingway. He was tough and hard-jawed. He braved the whitewater of a Georgia river and, as a boy played banjo and troubles gathered, led us into the strange, dark soul of America. You knew he’d endure. It was written on him. Like Ulysses.

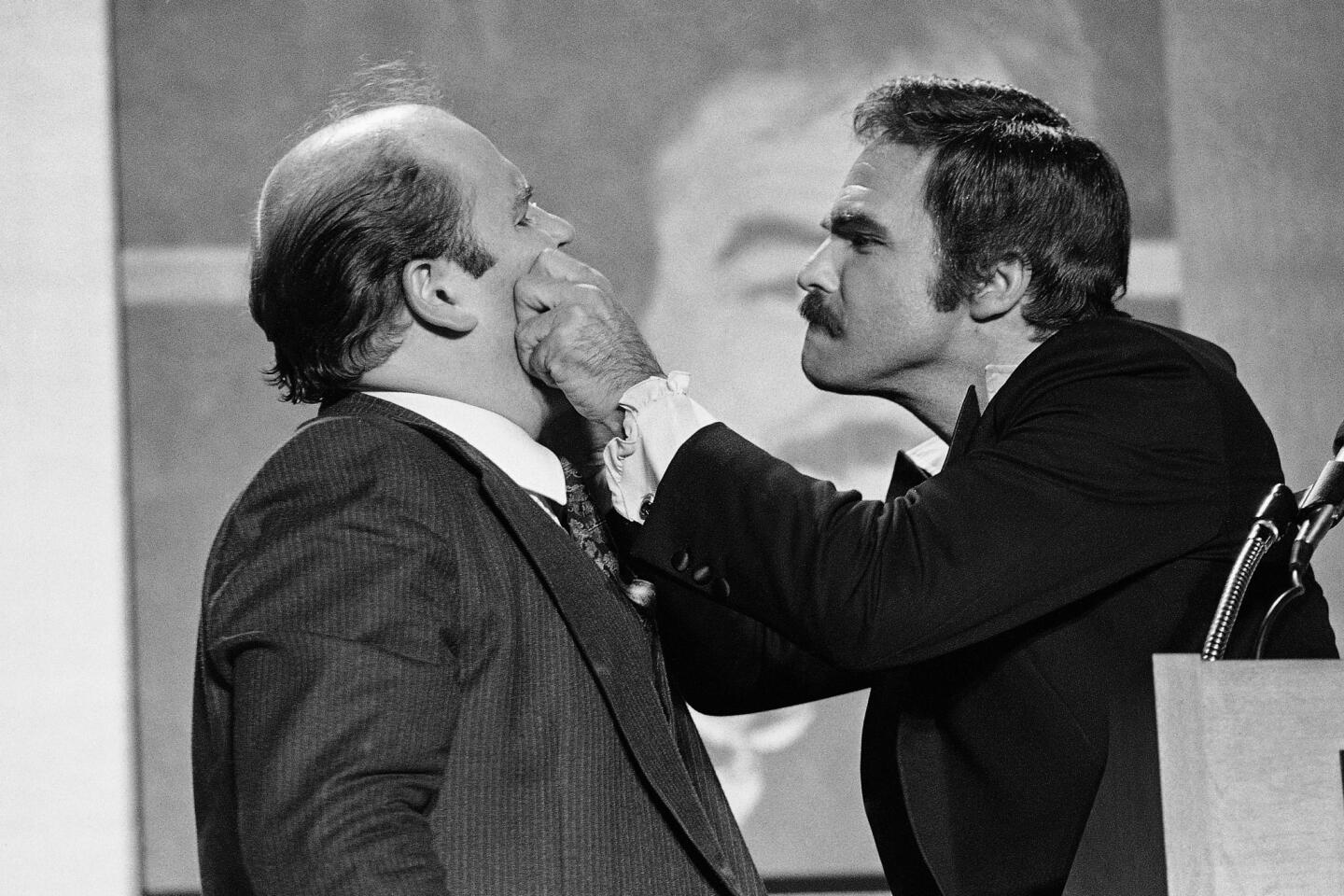

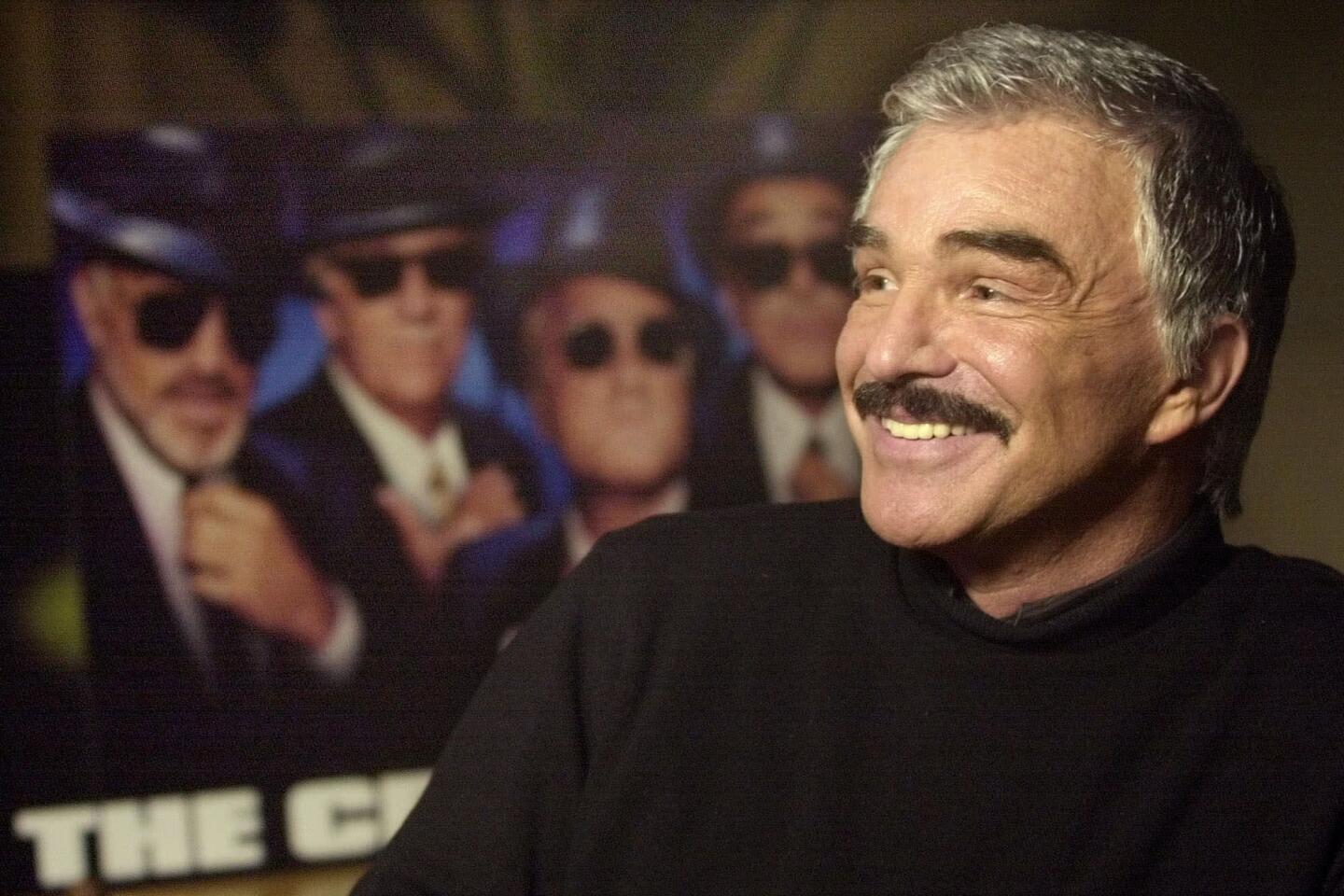

That was his gift, to understand the laws of nature and defy them, even if sometimes that’s impossible, in film and in life. It was all about staying clever, keeping your wits and finding humor in unexpected things. At times, though, I wondered if Reynolds pushed himself enough. He was ever self-effacing, but was he more seduced by the fun than by the hard work of his craft.

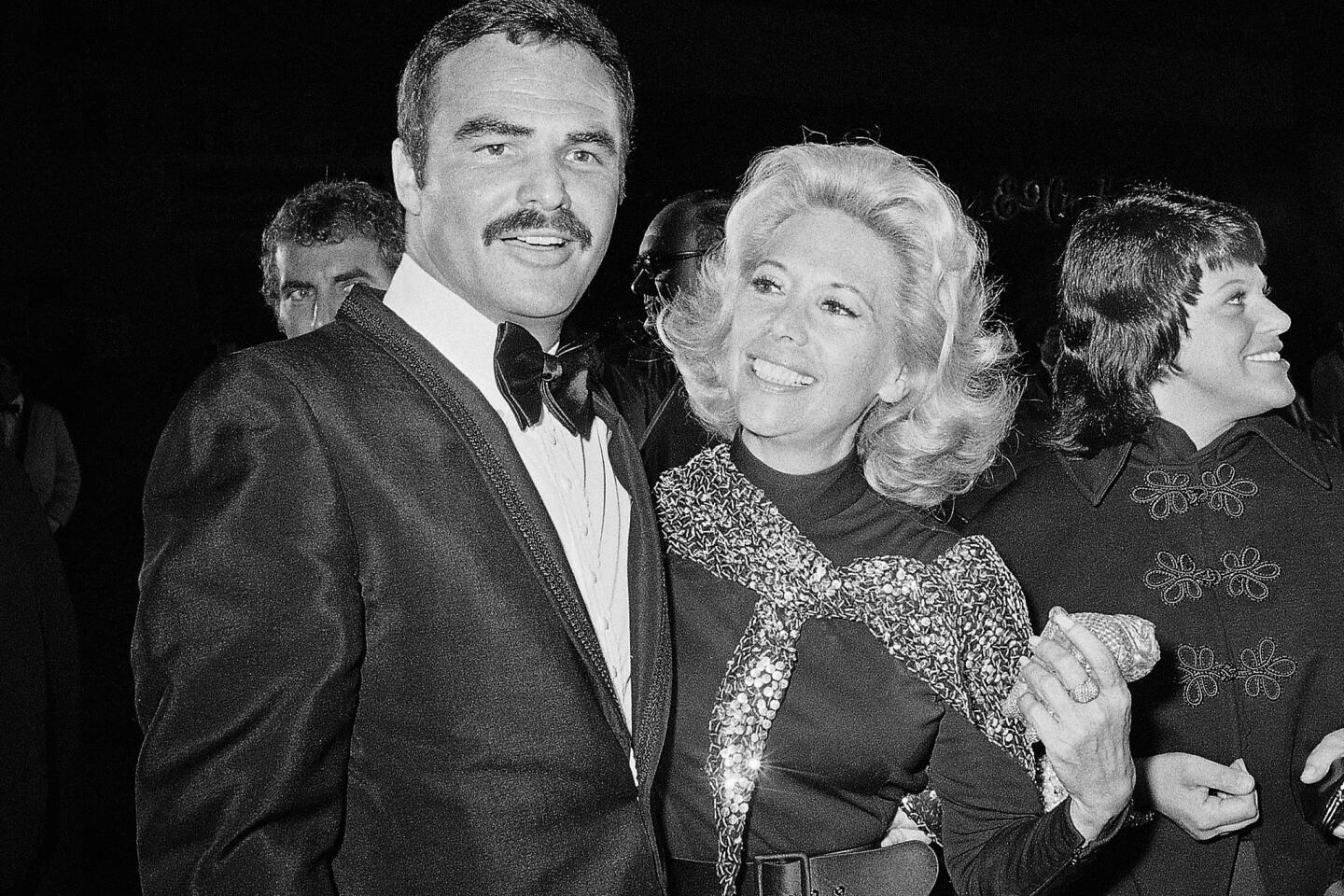

Many of his movies — the “Smokey” films, “The Longest Yard,” “Gator” and “Starting Over” — became a scrapbook for the 1970s, when Reynolds was in his effusive, rakish prime. They played as antidote in a nation that was emerging battered from the Vietnam War and tumbling through a post-Watergate era, when trust was shattered by images of body bags coming home and a president fleeing from the White House in shame.

Reynolds was ingrained in the times, pop-culture personified, an actor who posed nude in a Cosmopolitan magazine photo spread that was at once a lark and a statement. He regretted it; Hollywood took him less seriously. Some things cannot be outrun. He racked up his share of bad movies — some excruciatingly so — and told the New York Times in 1978: “I think I’m the only movie star who’s a movie star in spite of his pictures, not because of them; I’ve had some real turkeys.”

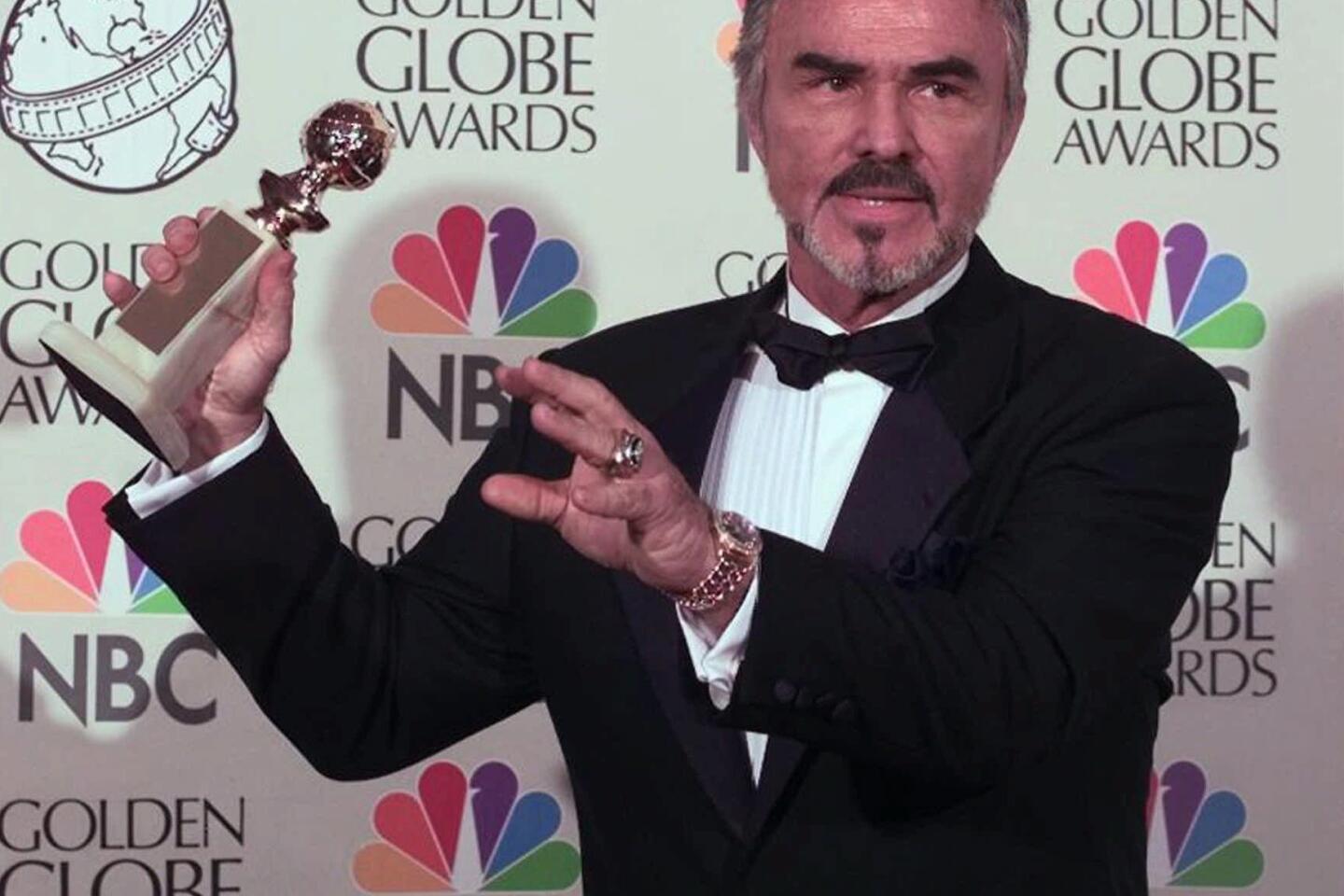

He dropped out of sight for a while. But he made a stunning return in “Boogie Nights” (1997) when his turn as a porn producer with a Cadillac and a silver-black toupee earned him an Academy Award nomination. In a diner scene, the texture of his voice changes from old to mischievous to forsaken as if a man whose sins are laid next to his disappointments: “You got maybe 15, 20 guys standing around making sure your lighting is right. . .If you don’t have those juices flowing down there and Mr. Torpedo in the fun zone. . .”

He was the Burt I knew from way back, only changed, carrying the things age turns into wisdom that bites and soothes. It was a voice of nuance and whispers. I was beginning to understand what he meant. The years were flying by me too, and, although he was much older, I liked that he was out there, causing a little ruckus, making eyes at the ladies, like he did when we were both young and I’d watch him from a row in the middle of a theater.

FROM THE ARCHIVES: Burt Reynolds is the comeback kid »

The last time I saw him was on TV in Adam Rifkin’s moving film “The Last Movie Star.” It’s a homage to Reynolds, who plays Vic Edwards, a forgotten film star invited to receive a lifetime achievement award in an obscure festival held by a shrinking fan base in the rear of a Nashville pub. He arrives thinking it’s something grander. It’s not. It’s an indignity and a lesson, a moment when a man must look at who he is, strip himself to his demons and flaws and carry on better in the time that’s left.

“I’m tired of feeling like a has-been,” says Vic, who lives alone with his booze, pill bottles and memories. “An audience will forgive a [terrible] Act II if you can wow them in Act III.”

When that sinks in, there is a kind of peace in the loneliness of an empty house.

Twitter: @JeffreyLAT

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.