Review: Rebecca Hall illuminates a reporter’s final weeks in the slow-burning ‘Christine’

Justin Chang reviews the new drama “Christine,” directed by Antonio Campos and starring Rebecca Hall and Michael C. Hall. Video by Jason H. Neubert.

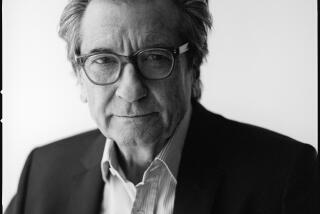

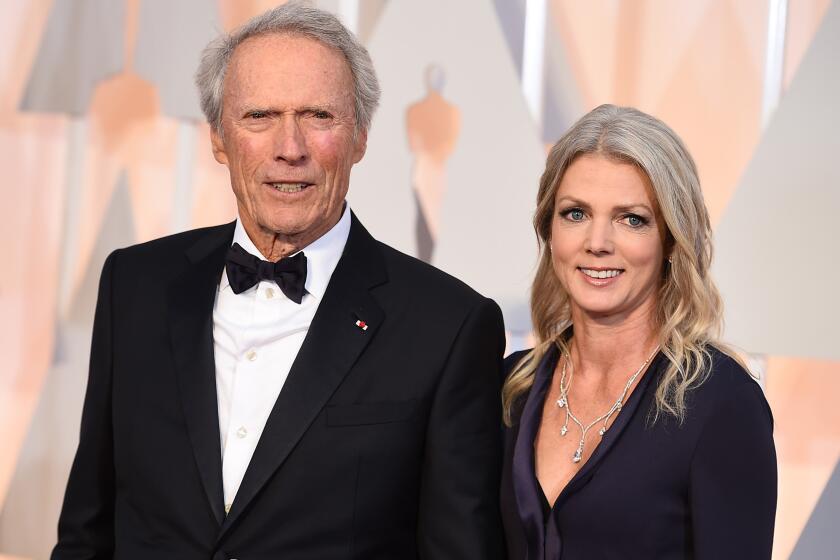

On July 15, 1974, Christine Chubbuck, a 29-year-old news reporter in Sarasota, Fla., drew a revolver and fatally shot herself during a live broadcast. It was a dubious first in the history of television, as well as a tragic, terrifying final gesture from a woman whose personal and professional misery ran agonizingly deep, as the director Antonio Campos has sought to unpack at length in his skillfully unnerving new drama, “Christine.”

By turns coolly observed and disquietingly compassionate — qualities that also describe Rebecca Hall’s brilliant central performance — the movie drifts alongside its subject, Charon-like, through the hell of her last weeks. It gathers implications and observations about her life and work and turns them into signifiers of psychological dread, slowly building a persuasive if not airtight case for why Chubbuck ultimately decided on her shocking course of action.

This isn’t the first time Campos has turned a caught-on-camera killing into the stuff of brooding cinematic nightmares. His little-seen debut feature, “Afterschool” (2008), was an icily brilliant formalist exercise that used a hideous accident to explore the rise of alienation and sociopathy in the Internet age. After getting at similar themes in the queasy psychosexual thriller “Simon Killer” (2012), Campos has now shifted his focus, with “Christine,” to the nature of image consumption in the pre-digital era, when the barriers separating news from entertainment were just starting to blur.

In an early scene, Chubbuck (Hall) notes, with strained professional bonhomie, that she’s always on the lookout for a good “human-interest story.” And “Christine,” for all its dramatic stealth and visual finesse, is honest enough to acknowledge its own place within that storytelling tradition.

A film of tough, roiling emotions and teasing insights into the gender dynamics and corporate media strategies of the ’70s, the movie shrewdly embodies the very tensions that Chubbuck finds herself wrestling with — caught between her desire to do respectable, socially relevant work and her newsroom’s “if it bleeds, it leads” philosophy.

Trying to make a name for herself at a time when women usually get ahead on perkiness and charm, Chubbuck dreams of ditching her soft beats (she hosts a morning community-affairs program, “Suncoast Digest”) and covering the sort of hard-hitting stories that might earn her a shot at national recognition. Yet her ambitions are repeatedly stymied by her bellowing station manager, Mike (Tracy Letts), who demands that she pursue juicier, more crime-oriented stories, all while expressing a growing frustration with Chubbuck that feels more personal than work-related.

You can’t entirely blame him, since most of the time, Chubbuck can’t seem to get out of her own way. Critiquing her own interview style, particularly her habit of nodding in sympathy with her subject, she notes, “It feels forced” — a description that describes her regular human interactions with often cringe-inducing accuracy. Hard, abrasive and perpetually ill at ease, she seems more authentic and likable in her moments of private anguish than she ever does in front of a TV camera.

Working the lower register of her voice and short-circuiting her natural spark, Hall pitches her performance at a level of extreme yet never over-the-top intensity. With her long, jet-black hair, her tall, thin frame and her abrupt, excitable physical gestures, she could at times be channeling a wraith in a Japanese horror movie, albeit one with a deeply human core.

The recurring sight of Chubbuck falling woefully short of her expectations, as well as everyone else’s, accounts for much of the movie’s slow-motion tragedy, as well as its almost imperceptible strain of acerbic comedy. Before it’s made explicit at the end, there’s an eerie, understated connection between “Christine” and the classic workplace sitcoms of its era, not least in the suggestions of romantic possibility ping-ponging around the newsroom. You sense it in Chubbuck’s conversations with George (Michael C. Hall), the golden-boy anchor for whom she pines from afar, and in her too-brief exchanges with Steve (Timothy Simons), a weatherman who seems as though he might be her friend and more if she gave him a chance.

She’s no less unhappy at home, in the apartment she shares with her mother (J. Smith-Cameron), whose friendly, outgoing personality and active dating life are a source of stability, shame and jealousy for the virginal Christine. It’s not the only manner in which the movie subtly channels the mother-daughter psychodrama and extreme performance anxiety of Darren Aronofsky’s “Black Swan” — one of several pictures with which “Christine” seems to have drawn inspiration, Sidney Lumet’s blistering 1976 classic “Network” and Dan Gilroy’s recent “Nightcrawler” not least among them.

But the movie with which “Christine” seems to be most in conversation is “Kate Plays Christine,” Robert Greene’s playfully probing meta-documentary about a real-life actress, Kate Lyn Sheil, researching the role of Chubbuck for a different (nonexistent) movie about her life and death. Remarkably, both “Christine” and “Kate Plays Christine” were conceived and produced independently of each other; both premiered in January at the Sundance Film Festival. A more fascinating, conflicted and oddly complementary double bill could scarcely be imagined.

A slippery formal and intellectual experiment, “Kate Plays Christine” (which opened theatrically earlier in the fall) implicitly calls into question the integrity of a more straightforward dramatic retelling like “Christine,” particularly with regard to the ethics of re-creating her on-camera suicide. (A tape of the incident is said to exist but has never been publicly released.) One of the conclusions of Greene’s rigorous deconstruction is that we can never fully know what motivated Chubbuck to pull the trigger, and on some fundamental level we shouldn’t be allowed to know.

But in “Christine’s” defense — and it’s well worth defending — the movie doesn’t entirely disagree. Campos’ approach to the story, though more concrete and conventional, is not without its own troubling ambiguity. Teeming with scenes that each shed new light on Chubbuck’s condition — a medical exam, the puppet shows she puts on for disabled kids at a clinic — the movie is by turns suggestive and blunt, coherent and inscrutable, and reluctant to settle on any one of the plausible explanations it raises.

What seems clear, at every step, is that Campos’ sympathies are entirely with his subject, even when those sympathies feel at odds with the fastidious attention to detail with which he has re-created Chubbuck, her milieu and her moment. There is something of a mortician’s perfectionism in the way the director attends to his movie’s surface, from the period-perfect cars and fashions to the drab, downbeat colors of Joe Anderson’s cinematography.

Campos clearly loves the technology of the period. As a study in how a 1970s TV station used to operate, the movie practically surges to life with a series of expertly acted and coordinated scenes of Chubbuck and her colleagues splicing negatives, rewinding reels and directing cameras. There’s more to these lively, percussive mini-montages than a fascination with minutiae. In capturing the atmosphere of a studio in all its buzzing, whirling glory, Campos’ film earns and provides the sort of validation that the real Christine Chubbuck surely deserved more of: the satisfaction of a job well done.

------------

‘Christine’

MPAA rating: R, for a scene of disturbing violence and for language including some sexual references

Running time: 2 hours, 3 minutes

Playing: Sundance Sunset Cinemas, West Hollywood

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

Movie Trailers

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.