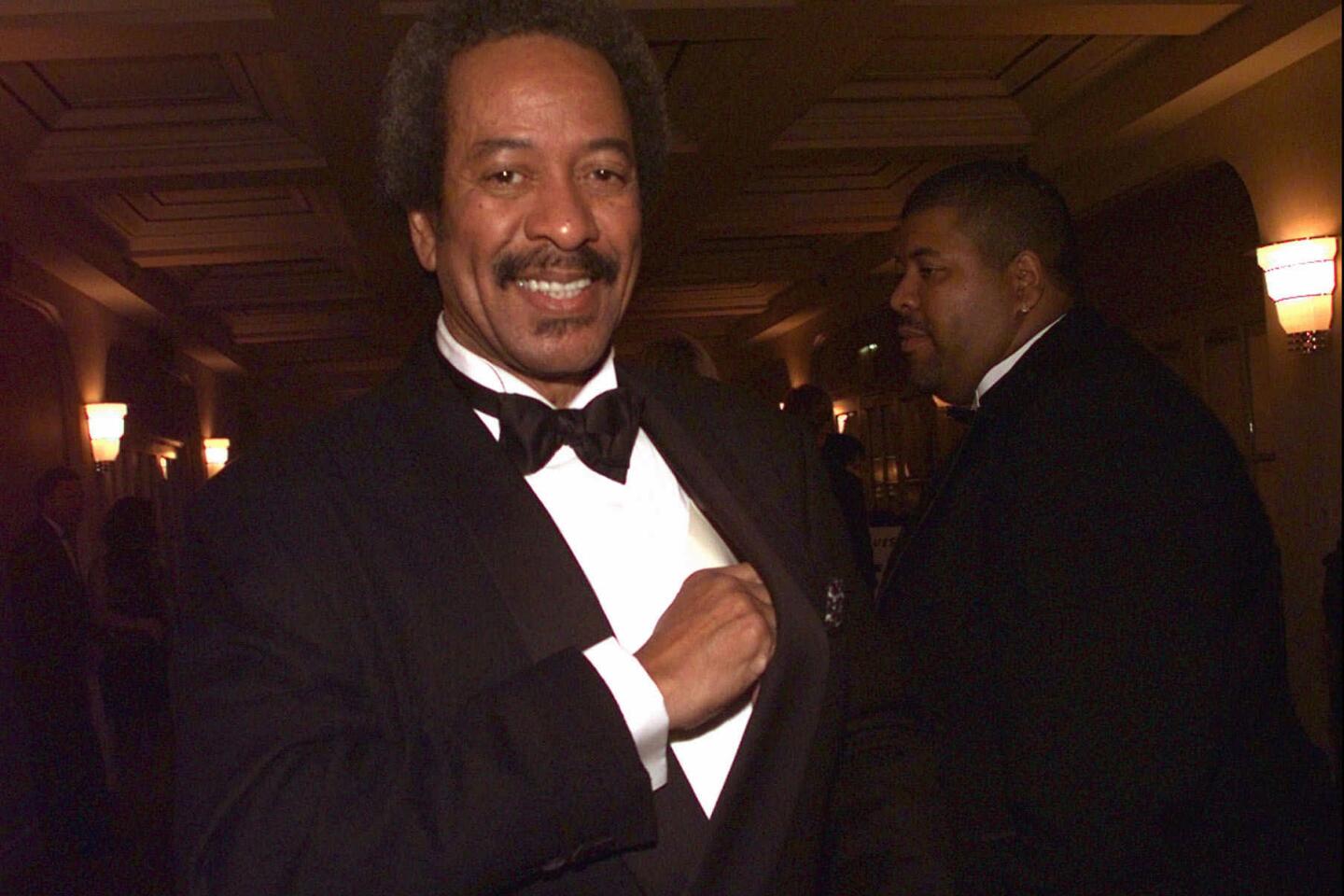

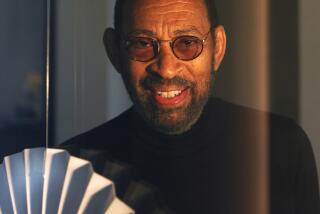

From the Archives: Allen Toussaint, keeper of the flame, puts words to his music

Nearly 23 years ago, Allen Toussaint, who died today at the age of 77, spoke to The Times about his low-key style and notable career.

There is no more rollicking and extroverted musical tradition in the world than the rhythm and blues of New Orleans.

Paradoxically, one of the most important shapers and keepers of that tradition is a quiet man who has been most comfortable working behind the scenes.

Allen Toussaint’s work as a songwriter, arranger, record producer and piano player was indispensable to the development of New Orleans music during the 1960s, when the city that had launched Fats Domino and Little Richard in the ‘50s rolled with a second wave of musical creativity.

Toussaint (pronounced too-SAHNT) played a vital role in helping establish the careers of such singers as Aaron Neville, Irma Thomas, Ernie K-Doe and Lee Dorsey. By the early ‘70s, when the Meters were serving as Toussaint’s main studio band, musicians from outside New Orleans were either flocking to his studio in search of some of his well-crafted funk, or sorting through his extensive songwriting catalogue for cover material.

Toussaint’s “Sneakin’ Sally Through the Alley” gave early impetus to Robert Palmer’s career; “Yes We Can” was a landmark track for the Pointer Sisters, and Boz Scaggs and Bonnie Raitt both recorded “What Do You Want the Girl to Do?” Toussaint’s pen also has yielded hits for such middle-of-the-road performers as Glen Campbell (“Southern Nights”), Herb Alpert (“Whipped Cream”) and Al Hirt (“Java”). Some harder-rocking bands also have been served: Devo remade “Working in a Coal Mine” (originally a hit for Dorsey), Warren Zevon and the Yardbirds covered “A Certain Girl,” and the Rolling Stones did a live version of “Fortune Teller.”

In between, Toussaint carried on a solo recording career that produced five albums between 1958 and 1978 (highlights from his ‘70s solo work are compiled on a 1991 retrospective, “The Allen Toussaint Collection”).

Over the past few years, Toussaint has branched into musical theater. He composed and directed the music for a 1986 off-Broadway production, “Staggerlee,” and was musical director of “The High Rollers Social and Pleasure Club,” a New Orleans R&B revue that had a month-long run on Broadway last spring.

Toussaint, speaking over the phone Wednesday from Sea-Saint, his New Orleans studio, said in his quiet, measured manner that jump-starting his recording career is “definitely not a priority” these days, even though his longtime partner in the studio, Marshall Sehorn, has been after him to make another solo album.

*

So if Toussaint isn’t looking for attention, what is this notorious homebody doing setting out on what will be the longest performing tour of his solo career? Along with Michelle Shocked, Joe Ely and Guy Clark, Toussaint, 55, will be part of the latest edition of “In Their Own Words,” an occasional series of touring songwriters’ showcases in which the panelists chat about their art, then put it to the test in live performance. The 18-city tour stops at the Rhythm Cafe in Santa Ana tonight.

Toussaint said he enjoyed the “In Their Own Words” format when he performed last spring at the Bottom Line, the New York City club that originated the informal talk-and-play sessions.

When an offer came to do an entire tour, Toussaint said, “I thought it would be fun, and also inspiring to be around other songwriters.” Toussaint said he doesn’t know Shocked, Ely and Clark, the three highly regarded Texas singer-songwriters who will appear with him tonight (Billy Vera, the Los Angeles band leader, radio host and R&B expert, will serve as non-performing moderator).

He is not worried about whether he’ll mesh with a new set of acquaintances. After all, as a producer and arranger, Toussaint has worked with quite an assortment of players, ranging from Paul McCartney, Elvis Costello and the Band to the members of Morrissey’s backing band, who cut a partial track with him at Sea-Saint last fall (Toussaint said that Morrissey, who never came to the studio, “didn’t feel up to doing the vocal then,” and the planned session was scrapped short of completion).

As he approaches the “Words” tour, Toussaint said, “My primary thought is that I was called to do what I do. I should be able to wake up in the morning and do that,” even in an untested combination involving performing partners who didn’t rehearse together before the tour, which was scheduled to begin Thursday in San Diego.

The concept of tossing together a panel of accomplished singer-songwriters, sending them around the country and seeing how they interact makes “In Their Own Words” an interesting and unpredictable addition to the standard run of concert tours (if you’re planning to be in New York on Feb. 19, you might look into scoring tickets for a high-powered “Words” one-nighter at the Bottom Line that will bring together Lou Reed, David Byrne, Rosanne Cash and Luka Bloom).

Toussaint’s longest previous tour was a two-week outing in 1975, after the release of his album “Southern Nights.” Since then, he has done some limited touring and appeared regularly at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival.

“I never feel that I’m prepared” as a performer, Toussaint said--but he has exacting standards for proper preparation. “The artists that go before the public, I would expect to eat, sleep and breathe getting ready to go before the public. I don’t do that,” because his own musical obsessions reside in the studio.

“I would have to plead guilty to not being as comfortable as I would expect an artist to be. An artist should be in love with the idea of going on stage because that is his or her forte. It isn’t mine. I’m not frightened, but I’m not as comfortable as I’d like to be. But it’ll be a change of pace from doing what I do here (at the studio) every day, at the piano, spending a lot of time alone.”

*

Lately, Toussaint has had some interesting company in the studio. His main new project is an almost-finished album titled “The Ultimate Session,” in which he is joined by “a number of guys who put (New Orleans) on the map.”

The musicians include Dr. John, who plays guitar, the instrument with which he made his first mark as a New Orleans session player before finding stardom as a great R&B pianist. Also on hand are Lee Allen and Red Tyler, saxophonists who have been mainstays of Fats Domino’s band, pianist Edward Frank and ace drummer Earl Palmer. Toussaint said he and Dr. John sing most of the songs together, covering a mixture of new songs and nuggets from the New Orleans R&B tradition.

Toussaint’s mother was a classical music buff; his father played the trumpet professionally but made his living as a mechanic’s helper in a New Orleans railroad yard. Toussaint began to play as a small boy on an upright piano that an aunt gave the family. In his teens, he began playing in bands, emulating the syncopated piano style of such New Orleans masters as Fats Domino and, especially, Professor Longhair.

Surprisingly, Toussaint says he culled those hometown influences from records and the radio, rather than from seeing Longhair and Domino perform in person.

“I was grown before I actually saw Professor Longhair’s fingers on the piano,” Toussaint said. “As a boy, I never got to where I could see him play the piano. I was over 20 before that happened. It didn’t dawn on me that I could go find these guys. It was the difference between the men and the boys, and I was a boy.

“I got all my influences off the records. I liked all piano players, but I felt a special kinship (with Professor Longhair and Fats Domino), something in the sound. There’s innately something that touches them that also touches me. In Professor Longhair’s case, it’s that syncopation associated with the second line in the Mardi Gras,” when a “second line” of revelers falls in and adds its own rhythmic embellishments to a traditional New Orleans brass parade band.

“It’s kind of a wild thing, definitely not 1-2-3-4. In Fats’ case (the influence) is the touch, and everything about it.”

In his early teens, Toussaint began playing in local bands. “As an early teen-ager, I met many of the guys and girls” who would have hits with his songs a few years later. “I knew they were special. I didn’t know what kind of mark they would make, but we were having a good time, and I knew it was different from the rest of the world.”

When Toussaint was still in his teens, Dave Bartholomew, Domino’s bandleader, heard him playing in a club and set him up with some recording sessions as a piano-playing stand-in for the touring Domino. During the ‘50s, Toussaint also toured as a backup musician for the duo Shirley & Lee. He launched his own recording career in 1958 with an instrumental album, “Wild Sounds of New Orleans.”

In 1960, Toussaint became house songwriter, arranger and producer for two local labels, Minit and Instant. The company names described his working method: He says he would often go in the studio and write a song while the singer stood by, waiting to record it.

Toussaint’s early credits as writer and producer included “Ooh Poo Pah Doo,” for Jessie Hill, “Mother-in-Law,” a No. 1 hit for Ernie K-Doe in 1961, and two other Top Ten hits the same year--Lee Dorsey’s “Ya Ya” and Chris Kenner’s “I Like It Like That.”

Nowadays, Toussaint said, his ideas have more time to ferment--including some that he would like to work into another musical. After his experiences as composer, arranger and bandleader on the “Staggerlee” and “High Rollers Social and Pleasure Club” productions in New York, “I would like to get in from the bottom to the top. That means getting in on (writing) the plot” and being involved in all other details of production. “I’ve been having ideas for years. Many of them I put down and then it goes into some archives in the cobwebs. But I have lots of ideas.”

Toussaint won a 1987 Critics Circle award for his “Staggerlee” score; last year, “High Rollers” met with mixed reviews and quickly folded--an experience that Toussaint took in stride.

“I don’t consider that a bad thing in my history, not at all,” he said of the play’s critical rebuffs and short run. “Maybe some people are doing something that causes cancer or World War Five,” so in the scheme of things, being one of the architects of a failed play wasn’t so awful.

“Some in the cast, it was like life and death to them. They had a wonderful vigor that I loved. But we were playing music, and no more. We were making music-- something fun and wonderful and legitimate.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.