‘School of Night’ at Mark Taper doesn’t do its homework

Few life stories are as densely packed with intrigue as Christopher Marlowe’s, the subject of Peter Whelan’s 1992 drama, “The School of Night,” which had its belated American premiere Sunday at the Mark Taper Forum. In addition to being the second-greatest Elizabethan playwright after Shakespeare, Marlowe was a rowdy Cambridge-educated poet-rebel, a profane apostate given to sententious drollery, probably a homosexual (as suggested by his infamous tag line, “Them that love not tobacco and boys are fools”) and very likely a spy.

If that doesn’t whet the gossipy appetite, his death at 29 -- the result of a vicious indoor brawl -- has excited enough conspiracy theories for an Oliver Stone biopic. Just imagine the film in which all motives lead to a fatal dagger plunged above the eye of London’s most audacious bad-boy.

But during the tedious, information-larded first act, I couldn’t help wishing for a new production of one of Marlowe’s own luridly comic tragedies, whose overreaching protagonists charge the stage with a plundering Renaissance determination to crack through known limits. The heavy blank-verse artillery of “Tamburlaine the Great” or “Doctor Faustus” isn’t likely to be reverberating in the Taper any time soon.

Yet Marlowe’s unbridled theatrical gusto, outlandish as it might seem to a culture weaned on Shakespeare’s exquisitely inward art, would make a better introduction to this canonical trailblazer than Whelan’s more pedestrian theater-history whodunit.

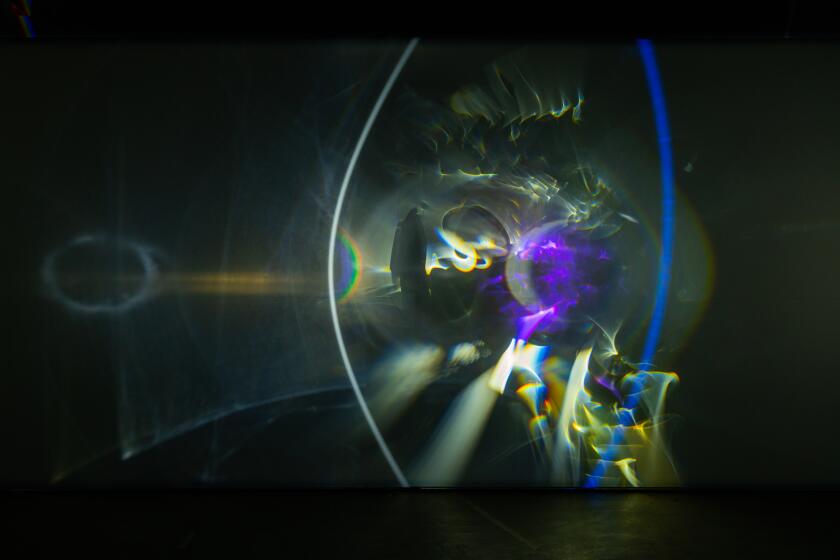

The production, directed by Bill Alexander (who staged the play for the Royal Shakespeare Company), is attractively arrayed on Simon Higlett’s spare wood-paneled set. Design-wise, the invitation to travel back in time is enticingly rendered. Russell H. Champa’s dim lighting heightens the sense of uncertain menace, and Robert Perdziola’s costumes manage to flaunt both bodies and frippery.

But the drama takes too long to find its stride. The sluggish setup situates us in Marlowe’s last months, when the fruits of fame proved to be no guarantee of safety in a society drowned in discord.

Paranoia was rampant in this treasonous urban caldron, and anyone rumored to have been members of “the School of Night,” the secret salon in which men such as Marlowe (Gregory Wooddell) and Sir Walter Ralegh (Henri Lubatti) once traded freethinking blasphemies, understood their days of London liberty were numbered.

The cat’s-cradle plot, informed by documentary sources and fleshed out by speculative fantasy, makes much ado about Marlowe’s irreverent wit in the face of brewing danger. But Wooddell’s “Kit,” as Marlowe was called, is like a blustering, unsinister Rupert Everett, who offered a fleeting but dashing Marlowe cameo in the 1998 blockbuster “Shakespeare in Love.”

Speaking of William Shakespeare, Whelan gives him a prime role in his tale, although there’s no evidence that Marlowe and he were buddies. (The most Stephen Greenblatt is willing to concede in “Will in the World,” his acclaimed 2004 study, is that “[t]hey must have known each other personally; the world they inhabited was far too small for anonymity.”) Here, Shakespeare (John Sloan), operating under the stage alias of Tom Stone, is portrayed as a sponge soaking up the planet’s lyrical wisdom. His professional livelihood depends on him being at once politically inconspicuous and opportunistic.

A scene in which Marlowe lectures Shakespeare, his junior by a couple of months but much further behind him in artistic stature (Bardolatry wasn’t an overnight phenomenon), signals the problem Whelan has in figuring out whether he is writing a murder mystery or a master’s thesis.

The topic under discussion is the purpose of comedy, and Marlowe comes out with such prissy remarks (“I know that we are never more vulnerable than when we laugh”) that he seems more like a doomed don than an enfant terrible constitutionally incapable of suppressing unauthorized truths.

Popular historical characters are hard to fictionalize. Indeed, it’s easier to go along with the portrait of a lesser-known light such as Marlowe’s ex-roommate Thomas Kyd (Michael Bakkensen), famous only for having written “The Spanish Tragedy,” than it is to accept a depiction of a quietly cocky young Shakespeare, who by 1592 would have had more reason to be jealous of Marlowe than the other way around.

The second act, launched by a delightful commedia dell’arte routine, deepens in thematic interest as Marlowe’s destiny darkly comes to fruition.

This turbulent theatrical golden age in which public and private selves literally bleed into each other is niftily re-created. But Marlowe’s “Edward the Second” or “The Jew of Malta” could better reveal why it’s worth remembering.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.