Los Lobos songbook drives ‘Evangeline, the Queen of Make-Believe’

The way Louie Pérez remembers it, there was nothing more all-American than growing up Mexican American in Los Angeles in the 1960s.

Yes, there were serious economic and social roadblocks to Latinos joining the middle-class mainstream.

But Pérez and his friends danced to the same music as their non-Latino peers, wore the same clothes — Sonny and Cher furry vests, anyone? — and tuned in and turned on to the same groovy counterculture experiments. They stood shoulder to shoulder for the same social causes, and many of them died fighting in the same southeast Asian war.

“The Chicanos in the ‘60s didn’t live in a vacuum,” Pérez, principal lyricist and multi-instrumentalist of the legendary East L.A. rock band Los Lobos, said recently. “We watched ‘Beverly Hillbillies,’ and we all drooled over Elly May and all that stuff. My sister, they came over to the house to watch Ed Sullivan present the Beatles, and they were all screaming and pulling their hair and crying and stuff in the living room of my house in East L.A.”

This spring, Pérez and a simpatico group of artistic collaborators are revisiting that formative time and place and reassessing the influence of the era’s revolutionary ideals in a new musical play that draws deeply from both the ‘60s zeitgeist and the prodigious songbook of Pérez and bandmate David Hidalgo.

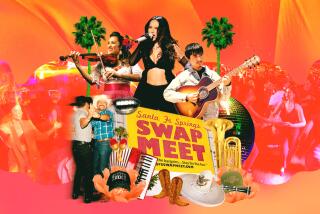

“Evangeline, the Queen of Make-Believe,” which Saturday night opened a three-week engagement at the Bootleg Theater, midway between Echo Park and MacArthur Park, is the first sanctioned theatrical piece to incorporate the music of Hidalgo and Pérez, the Lennon and McCartney of bi-lingualrock ‘n’ roll.

The multimedia show, which uses video projections by cinematographer Claudio Rocha and a live on-stage rock band led by Scott Rodarte of Ollin, also is one of the few stage works to depict a watershed period through the perspective of a young Chicana who’s struggling to find her identity amid family pressures and cultural upheavals. By day, Evangeline is a dutiful daughter to her recently widowed, very traditional mother, tending house and watching over her restless younger brother.

But at night she discovers another universe, only a few miles distant but culturally worlds apart from her East L.A. home: the art galleries and fabulously louche night life of the swinging Sunset Strip, where she becomes a go-go dancer and meets her future boyfriend James, a non-Chicano student activist. Another important plot thread is the 1968 Chicano student walkouts at L.A. high schools, a landmark event in the evolution of Mexican American political power.

Altogether, “Evangeline” enfolds about a dozen Los Lobos songs, including “Revolution,” “Good Morning Aztlán,” “River of Fools” and the rollicking 1985 title tune about a teenage girl who fled her home and “ran off to find some American dream.” There also are three songs by the Latin Playboys (a Los Lobos offshoot) and a handful of period songs by other groups (“Judy in Disguise,” “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg”).

The stage band’s lead singer, CAVA (née Claudia Gonzalez-Tenorio), acts as a kind of all-seeing community conscience called the Neighborhood. Pérez said that his old neighborhood still sometimes functions as a mental stage-set for the stories that he dramatizes in song.

“Songwriting for me, the words always came from some visual place, and I always imagined people that populated these songs,” Pérez said. “This is an opportunity to really actually see flesh and blood people on-stage.”

Pérez and the show’s other creators, Theresa Chavez and Rose Portillo, who also co-direct, can relate first-hand to the era of bilingual consciousness-raising that “Evangeline” depicts. They lived it growing up in Los Angeles.

“Eva is claiming territory — personal, political, social, musical, artistic, sexual,” said Chavez, a producer, playwright and artistic director of 23-year-old About Productions, which developed “Evangeline.”

“She goes to the La Cienega Art Walk, she goes to Laurel Canyon. The piece isn’t just about Sunset Strip, it’s about what was going on in L.A. in the ‘60s, about the notion of what constitutes art, what constitutes a painting, what constitutes an individual’s political identity — does it have to be fixed?”

Catherine Lidstone, 23, who plays Evangeline, said that although her character is technically a born and bred Angeleno, the show taps into the universal American immigrant quandary of trying to reconcile family loyalty with the need to assimilate an adopted country’s values. To prepare for the role, she has been watching documentaries about the Chicano power movement and episodes of “Hullabaloo,” a mid-’60s music variety TV show.

“What’s cool about her [Evangeline] and I guess what influences her from the period is that free-thinking mind-set of ‘Maybe we’re not just supposed to do what we’re told, and maybe the people who are telling us to do things don’t know everything about the situation,’” said Lidstone, the daughter of a U.S. father and a mother from Trinidad and Tobago. “I think that part of growing up is really important, and I feel like in the ‘60s they had such a beautiful open window to do that.”

Fashioning a musical play from Los Lobos’ catalog would seem such a natural subject for an L.A. theater company that it’s a mystery it hasn’t happened before. Pérez said he’d been in discussions a few years ago with the Mark Taper Forum about developing a theater piece based on the band’s 1992 experimental chef-d’oeuvre “Kiko,” but the project “got caught up in so much red tape.”

Then about four years ago, Pérez broached the idea of a theater piece after running into Chavez while performing a fundraising concert at Plaza de la Raza. “I wanted to see if there was life after rock ‘n’ roll,” the 59-year old musician said. “Not that I’m unhappy. I’ve got the most incredible story to tell to my grandkids. But I wanted to do other things.”

Working closely with Pérez, Chavez and Portillo began to develop a story, setting and dialogue that could be framed by Los Lobos’ evocative music. An initial workshop production in June 2010 was followed by a panel discussion, “Civil Rights and Go-Go Boots,” that combined excerpts from the show, an academic skull session and soliciting community feedback about the then show-in-progress.

The development process continued with a concert reading last June and a weeklong residency by the creative team at the Autry National Center, coinciding with the regionwide multi-venue “Pacific Standard Time” exhibition chronicling L.A.’s post-World War rise as a major art-world center.

A touring version of the show, with Pérez and Hidalgo performing the music live, is planned to begin next spring with stops at several Central Valley community colleges.

Accessorized with magical-realist touches and psychedelic colors, “Evangeline” offers much for Eastside history buffs and ‘60s cultural connoisseurs to savor. Although the show looks backward 40 years, its creative team set out to make a contemporary show, not a period one.

“To do a piece of nostalgia is not important to us. That’s not a good reason to do theater,” said Portillo, a writer, visual artist and actor who played a lead role in the original production of “Zoot Suit,” Luis Valdez’s landmark play based on the 1942 Sleepy Lagoon murder trial in Los Angeles.

But if “Evangeline” isn’t exactly a trip down memory lane, for Pérez it has been a timely low-rider cruise through familiar haunts that remain creatively vital.

“I’m so fortunate to have met Rose and Theresa,” he said, “because it’s kind of brought me back to this side of town, physically and existentially.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.