‘The Girl on the Train’

True-life-inspired tales such as “The Blind Side” or “Invictus” are a common part of modern American moviemaking, but that tendency is far less pronounced in French cinema. Nevertheless, in his latest film, “The Girl on the Train,” veteran French filmmaker André Té chiné takes on a 2004 news story of a girl who faked an anti-Semitic attack that turned into a media and political firestorm.

“What appealed to me was to tell the story of a lie,” said Téchiné recently by phone from Paris, via translator. “I was really interested in tackling the genealogy of a lie.”

As the film opens, Jeanne (Émilie Dequenne) is struggling to find her way in life. Her mother ( Catherine Deneuve, appearing in her sixth Téchiné film) tries to get her a job with an old flame, Bleistein (Michel Blanc), now a successful lawyer. After a budding romance takes a disastrous turn, Jeanne concocts a story of being attacked on a subway train, invoking anti-Semitism (even though she is not Jewish) and never expecting the media furor that erupts.

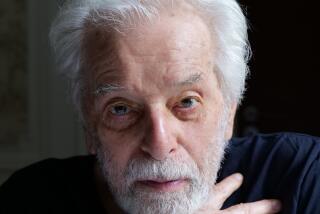

Téchiné, 66, occupies a unique position within the landscape of contemporary French filmmakers. Though he started as a critic at the famed journal Cahiers du Cinema, he began his filmmaking career in the post-New Wave era. He achieved a certain amount of international notice with such early films as “French Provincial” (1975) and “The Brontë Sisters” (1979).

He was something of a mentor to Olivier Assayas early in his own transition from critic to director, as the two collaborated on the screenplays for 1985’s “Rendez-vous” (for which Téchiné won the best director prize at Cannes) and 1986’s “Scene of the Crime.” Téchiné also achieved acclaim for 1994’s “Wild Reeds,” 1996’s “Thieves” and 2003’s “Strayed.”

He has never quite had his popular breakthrough in the United States, although writing in the Village Voice in 1995, Howard Feinstein positioned him among filmmakers in France as “one of the few commercially viable intellectual auteurs.” In his “The New Biographical Dictionary of Film,” David Thomson echoed that sentiment when he referred to Téchiné as “a fairly reliable source of intelligent entertainment.”

For “The Girl on the Train,” Téchiné collaborated on the screenplay with Jean-Marie Besset and Odile Barski. Besset had written a play based on the true events that inspired the story. Barski, on the other hand, collaborated specifically on creating the sense of the lawyer’s tight-knit Jewish family that becomes prominent in the second half of the film.

“The film is like an experiment in Cubism, it’s split in two,” said Téchiné. “In the first part we have the portrayal of this young woman and how she constructs her life, taking elements from reality. In the second part it is as if it was suddenly a different movie because she belongs to other people’s perceptions.

“It’s the story of her judgment, of the monstrosity of this lie, an aberration of which she is not aware because she is blind to it. I was interested in the intersection of the social aspects and the psychic aspects.

“For me, the fact she identifies to be an anti-Semitic victim is completely monstrous, yet at the same time it is her survival strategy, it is her cry. It is absolutely irresponsible, but it is the way she expresses her need for love and attention.”

Though Téchiné’s telling of the story does give a fairly concrete sense of why the young woman did what she did -- mostly revolving around a need for attention from her boyfriend and mother -- he is also able to maintain a sense of enigma and mystery around the character, someone who remains captivating for her lack of a graspable essence. Dequenne, familiar to art-house audiences for her riveting performance in the Dardenne brothers’ 1999 film “Rosetta” (for which she won the best actress prize at Cannes at only 17), captures the odd sense of being somehow physically grounded and yet emotionally distant.

For Téchiné, the point of what is or isn’t from the actual case isn’t that important. Rather, he prefers to think of the film as a way to cut through to the issues that he found most intriguing.

“If you want, there is another way of articulating this, that my strategy consisted of cleaning up the news item from its confusion,” he said. “In a way, I got rid of the media mud, the garbage that surrounded it that prevented us from seeing the affair as it really was. I wanted to restitute the human dimension to the news affair.

“The complexity of this whole affair is that it is a lie that paradoxically is actually talking to the truth,” Téchiné added. “There has been anti-Semitic aggression in France, and I show that in the film. In order for the character to create this lie, she has to dig into the evening news on television. To create the story, she has appropriated a reality that doesn’t belong to her.”

Well into his fifth decade of filmmaking, Téchiné insists he still feels a thrill each time behind the camera.

“I think I conceive of every film as if it were my first and my last one,” Téchiné said. “I want to embark on an adventure that’s completely different in hopes of finding an unknown landscape. I like to feel like an explorer who doesn’t know what he’s going to discover.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.