Re-creating a time of peace in the Balkans

High in the mountains of Serbia sits a fairy-tale village full of wooden huts built in a style that hasn’t changed in 300 years. You’ll find French legend Isabelle Huppert and Cannes general delegate Thierry Fremaux hitting the slopes and Belgium’s Dardenne brothers discussing the origins of a story with a young director after screening their latest, “The Kid With a Bike.”

Iran-born “Persepolis” director Marjane Satrapi enjoys a cigarette at the Visconti restaurant, surrounded by adoring fan boys praising her new film, “Chicken With Plums.” Korean director Kim Ki-Duk, with a smile on his face, carries an intricate carving of a tree, the “Award for the Future Movie,” back to his cabin, and American director Abel Ferrara, after screening “4:44 Last Day on Earth,” dances to Balkan music till 2 a.m. while encircled by energetic film students.

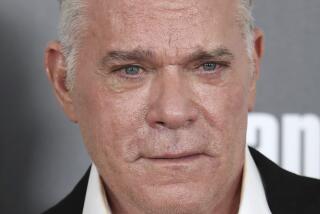

In between everything, a bear of a man is running back and forth, shoelaces untied, hair askew. Emir Kusturica, director of the fifth annual Kustendorf Film and Music Festival, held here in January, doesn’t take a moment to pause, finding time each night to join the dancing-on-tables, Balkan-style parties that don’t wind down until dawn amid piles of empty raki glasses.

The Sarajevo-born director and darling of European cinema is best known for making surreal and darkly comedic films about the Balkans. He is also among the few filmmakers to have won the Palme d’Or twice at Cannes: for “When Father Was Away on Business,” a delicate film on life in communist Yugoslavia, and “Underground,” an ultimately antiwar film that reminisces about the trials of the former Yugoslavia. Kusturica has also received much heat over the years from native Bosnians for renouncing his Muslim roots in 1995 at the end of the Bosnian War, when he was baptized into the Serbian Orthodox Church. He has not since returned to Sarajevo.

Today, Kusturica identifies completely as a Serb, splitting his time for the last eight years between Paris and Kustendorf, the village inside Mokra Gora that he was inspired to build after filming “Life Is a Miracle” in the area. Through his work in portraying Serbia and creating arts and cultural projects such as the film festival, Kusturica has ensured his place in the canon of the Balkan country’s art. “He’s proof that it doesn’t matter where you come from,” said Slavko Stimac, who has played some of Kusturica’s most unforgettable characters. “You can make it if you have something to say.”

Kusturica has made it abundantly clear that his purpose in life goes well beyond that of making great cinema. At 57, he tours the world with his No-Smoking Orchestra, makes time to work on his fiction and maintains a side career as an actor. He has three films in development, all with French production attached, including a biopic on the Gypsy guitar prodigy Django Reinhardt and a Pancho Villa love story. Kusturica is hoping Benicio Del Toro will sign on for the lead, though he will start production in December with or without him.

But Kusturica’s real passion today lies in extending his cinema into real life through architecture and city planning. “It’s very important to have a place which is absolutely outside of any feelings of civilization,” he said in one of his rare instances of sitting down during the festival, inside his cozy library at Kustendorf. The room and its furnishings, as with the rest of the property, were built locally. Heavy wooden armchairs are surrounded by playful folkloric paintings. Just outside the library is a helicopter pad overlooking a range of snow-kissed mountains. “It’s a realized utopia.”

The village is packed with set photos of the director in various intimidating guises: posing with an assault rifle, commandeering a four-wheeler, kissing a brown bear on the mouth. In addition to managing Šargan-Mokra Gora, the region’s nature park, he owns two hotels on the property and is building a third.

On a well-trafficked summer day, upward of 2,000 people visit the site. “He’s feeding a village that was almost empty and much more than that,” said Snjezana Marinkovic, who assists Kusturica in running the park.

Much of Kusturica’s work since 1995 has focused on rebuilding through art his lost country, a Yugoslavia to which he attributes a 50-year era of peace. “I think when I lost my country, one guy said, ‘He lost his country, he lost his own city, he’s now living in his cinema.’ And it sounded good, but I didn’t feel good,” Kusturica said with a frown. “And then I said, ‘If I lost it all, I will re-create with all my potential what used to be.’ ”

Yet while in Kustendorf, Kusturica has captured a particular moment in centuries-old craftsmanship; he’s now embarking on his largest project: building a city out of stone inside Višegrad, just over the border in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Kamengrad is his remedy to the unfortunate fact that war has obliterated most concrete examples of Balkan history here. The new construction will re-imagine this history, from the Ottoman Empire through Austro-Hungarian conquest, using Noble Prize winner Ivo Andric’s novel “The Bridge on the Drina” as a blueprint, literally and figuratively.

Kusturica was 17 when he first read the novel, a book he refers to as the Serbian Old Testament. In one passage, Andric writes of how a flood brought Christians, Jews and Muslims together to rebuild: “The force of the elements and the weight of common misfortune brought all these men together and bridged, at least for this one evening, the gulf that divided one faith from the other.”

Kusturica brightened at the mention of this story. “You know, in each segment of ex-Yugoslavia, multi-ethnic life is lost, except I think we somehow still have this in Serbia,” he said. “This city has to bring back the stage in which this life is possible, because Sarajevo is not anymore the multi-ethnic city that it used to be.”

The construction is a joint venture with the state government of about $20 million. Kusturica’s ambition is vast: an Andric institute, a mayor’s house , an outdoor market, a Turkish caravansary, an academy of arts, plus a center for Slavic studies and a replica of the medieval Deeani church, which stands today as one of the oldest in Serbian heritage. The centerpiece is a national theater that will open with a Kusturica-directed opera based on “The Bridge on the Drina,” which he is adapting.

“You know, a lot of people have been killed, thrown from the bridge in history, a lot of people slaughtered,” said Kusturica. Kamengrad is “fighting nature, fighting animosities, fighting people who are against real culture, which is very often here the case. And I hope that this, what I do, it will help young people to understand better that they have to avoid war by all means.”

--

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.