‘The Knick’ is a new twist on the TV doctor show

At the Knickerbocker Hospital in New York, ambulance drivers get kickbacks for delivering patients, women regularly die from routine pregnancy complications and the chief of surgery’s a strung-out cocaine addict who refuses to allow his black deputy to operate on patients. Did we mention there’s no electricity or antibiotics?

Thankfully, the people of New York are in no danger — not anymore, that is — of landing at the embattled institution at the center of the series “The Knick,” premiering Aug. 8 on Cinemax. Set in 1900 at a time of sweeping change in the city and the world of medicine, the show throws viewers headlong into the seedy underbelly of turn-of-the-last-century Manhattan.

In the pilot’s opening minutes, Dr. John Thackery — played by Clive Owen in his first series role for American television — awakens from a stupor in a Chinatown opium den, hops in a horse-drawn cab and injects cocaine in his toes as he winds through the teeming slums of the Lower East Side. Arriving at the Knick, Thackery scrubs in and in a spectacularly gruesome sequence few viewers are likely to forget, attempts to save a pregnant woman with placenta previa, a complication that once spelled certain death for both baby and mother.

Let’s just say it doesn’t go well.

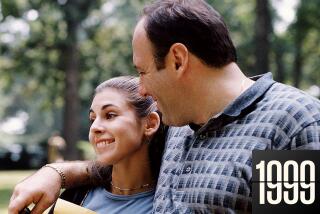

“It’s a bit like, ‘Welcome to 1900!’” Owen said recently over cappuccino at the Mercer Hotel in Soho, a few cobblestoned blocks (but a world away) from the imagined home of the Knick in what’s now the East Village. Since breaking through stateside in Mike Hodges’ sleeper hit “Croupier,” released here in 2000, Owen has brought his suave intensity — just don’t call him “brooding” — to “Gosford Park,” “Children of Men” and the romantic comedy “Words and Pictures.”

His role as a “crazy and abrasive and unpleasant and tough” drug addict is likely to do little to distance Owen from the “B” word. “He’s dark, and he’s complicated. He really is. I’m sure one of the reasons I was excited by him is I’ve always loved playing somebody who’s uncomfortable.”

“The Knick” is novel not just for its decidedly unsentimental view of the recent past. In a rarity for series television, the entire 10-episode first season was directed by a single Oscar-winning filmmaker, Steven Soderbergh. And despite its prestigious TV bona fides (charismatic antihero, A-list film-world talent, period setting), it’s airing on Cinemax, a cable network more associated with smutty late-night fare and shoot-’em-up action shows than with the Emmy bait regularly seen on HBO, its more sophisticated sister channel. Despite the risks, “The Knick” has already been renewed for a second season, once again to be directed by Soderbergh.

‘The doctor show’

In May 2013, just as his Emmy-winning Liberace biopic “Behind the Candelabra” was set to premiere on HBO, Soderbergh declared his retirement from feature films and said he was looking forward to painting lessons.

That’s when the script for “The Knick” landed on his desk, courtesy of his manager, Michael Sugar, of Anonymous Content. The project came by way of Jack Amiel and Michael Begler, a screenwriting duo whose family-friendly credits (“The Shaggy Dog,” “Big Miracle”) hardly suggest the capacity for stomach-churning spectacle.

“I just knew it was going to go fast,” Soderbergh said during a conversation in his tidy, compact Tribeca office. “The foundation was the most indestructible genre in television, the doctor show, but I hadn’t seen this context before.”

The series came about when Begler, amid a personal health crisis in 2012, began researching the history of medicine. “I found myself at times really amazed at what the world had figured out and at some points really frustrated with what we still had to figure out,” he recalled. “It just made me start to think about the general question of ‘Why do we know what we do?’ ”

After snatching up vintage medical textbooks on EBay, he and Amiel quickly decided fin de siècle New York would make a rich backdrop for a television series. “It was a society going through changes so fast that people’s hair was being blown back,” Amiel said.

Following “Mad Men,” “Boardwalk Empire,” “Manhattan” and “Downton Abbey,” “The Knick” is the latest high-brow series to mine the history books for drama. And though a work of fiction, it is rich with real-life influences. Owen’s Thackery, an obsessive surgeon helping lead his nascent discipline out of the barber shop and into the realm of science, was partially inspired by William Stewart Halsted, a famed New York surgeon and educator who also happened to be a cocaine addict.

“Thackery is a guy who is always pushing forward and desperately trying not to look back because he’s got a load of bodies behind him,” Amiel said. “Cocaine gives you courage and stamina, two things that these guys needed at the time.”

Drug dependency is merely one of Thackery’s shortcomings: He’s also verbally abusive to his staff, including a wide-eyed nurse (Eve Hewson) and his black, Harvard-educated deputy chief of surgery (André Holland), and he openly flouts orders from the proto-feminist heiress (Juliet Rylance) who heads the hospital’s board of trustees.

The grim financial situation at the Knick doesn’t help Thackery’s mood. (An actual Knickerbocker Hospital once existed in New York, but this is merely a coincidence, say the series creators.) With the city’s elite fleeing uptown, the hospital is left to serve the ever-increasing waves of impoverished immigrants crowding Lower Manhattan.

“It’s a great way to look at a very exciting city at a very dangerous time,” Owen said, “because you can go into the world of the people who are funding the hospital, or you can go into the slums where diseases are breaking out. New York was pretty wild in those days.”

Soderbergh offered the project to Owen, a performer he’d never worked with before but whose “flawless reputation” intrigued him.

Owen, who first made a name for himself in British TV in the con man drama “Chancer” and as a private detective in “Sharman,” but hadn’t done a series in nearly two decades, was intrigued but wary of the 10-episode commitment — that is, until he read the script. Unlike many other period dramas, he said, “The Knick” “wasn’t polite and restrained, it felt very contemporary.”

HBO would seem to be the perfect home for such a project, but Soderbergh suggested Cinemax during a conversation with HBO’s president of programming, Michael Lombardo.

With a short window of availability in which to film, he figured he could get a faster greenlight from Cinemax — plus, he said he “honestly wanted to be the tall poppy over on the other channel.”

The show’s writers were also excited about the possibility. “People say, ‘Cinemax?’ but they said that about Netflix two years ago and Showtime four years ago,” Amiel noted. “What we’d love to do is be the ones to change the game at Cinemax.”

Until Soderbergh’s proposal, Lombardo hadn’t thought of “The Knick” as a project for Cinemax, which in a bid to attract more subscribers and shed its “Skinemax” reputation began to venture into original series a few years ago with the action-oriented “Banshee” and “Strike Back.” “It was the first time we decided to produce a show for Cinemax that at every step of the way would work on HBO,” he said, “and that’s OK. We decided there are areas where the two will overlap.”

By mid-June 2013, the project was a go. Soderbergh wanted all 10 episodes written before the beginning of production in September in New York. This meant Amiel and Begler had to churn out nine additional scripts in just three months, all without the benefit of a traditional writing staff. Soderbergh enlisted screenwriter Steven Katz, who’d worked on the never-realized film adaptation of “The Alienist,” Caleb Carr’s bestseller about a serial killer in 1896 New York City.

“When you need facts about a 1900s prostitute, he’s your guy,” Amiel said.

The team

Though television has traditionally been considered a writer’s medium, dominated in recent years by superstar show runners like Matthew Weiner, David Chase and Vince Gilligan, directors including Jane Campion (“Top of the Lake”) and Cary Fukunaga (“True Detective,” which like “The Knick” was packaged by Anonymous Content) have also been making their mark lately. “The Knick” is likely to further complicate the question of television authorship: Not only did Soderbergh direct but he also shot and edited all 10 episodes, as he’s done on most of his projects since “Sex, Lies, and Videotape.”

The director edited the day’s footage at night, usually putting together an assemblage in two hours. “There’s no fat,” Owen said of Soderbergh’s process. “He only shoots what he needs. He doesn’t say, ‘I’ll do this and I’ll do that and I’ll look at it later.’”

As a cost-saving measure, the series was filmed out of order and in blocks at each location, like a 10-hour movie, rather than episode by episode. This meant cast members would often have to jump between scenes from multiple episodes in a single day — a challenge for Owen, whose character undergoes a dramatic emotional journey enhanced by cycles of cocaine frenzy and withdrawal. A whiteboard listing scenes and episodes helped keep his head in order but, said Owen, “anybody who works with Steven knows very quickly: Get your ... together.”

“Low Life,” Luc Sante’s colorful history of the New York underclass, was required reading for cast members. Holland also turned to W.E.B. Du Bois’ “The Souls of Black Folk” to get into the mind-set of his character, while Hewson (daughter of U2 frontman Bono) read up on the history of nursing.

Dr. Stanley Burns, an ophthalmologist who founded the Burns Archive, which claims to be the world’s largest collection of early medical photography,acted as a technical adviser.

While Soderbergh aimed for ruthless authenticity in depicting the horrors of late Victorian-era surgery, he and the writers were careful not to be too fussy about language or strict verisimilitude. The goal, Soderbergh said, is to make the audience “focus on the ways in which their lives are like [the past], as opposed to the ways in which they are not.”

The director’s hand-held camera work and a hypnotic electronic score by Cliff Martinez added to this sense of immediacy.

Despite the blistering (not to mention budget-friendly) pace of production, “The Knick” helped Soderbergh rediscover his love of storytelling. “I really did walk away feeling like this is my job, this is what I’m built to do and that’s why I’m lucky.”

The cast, though, never quite became inured to all the blood and viscera, however fake it might have been. With a wince, Owen recalled an operation in which his character was “literally corkscrewing into someone’s head,” while Hewson was put off by an actor outfitted with a prosthetic dislocated jaw. “Steven just told me, ‘Don’t look at it, because you’re going to get sick.’” Wisely, she listened.

Twitter: @MeredithBlake

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.