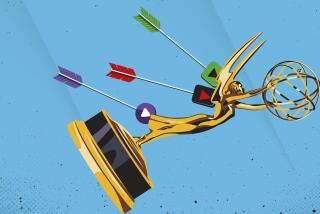

Critic’s Notebook: TV’s new microaudiences are shaking up the business

The business end of show business is made up of numbers. It’s a thing of charts and tallies, receipts and ratings. There are counters on everything nowadays, toting up the hits, keeping track of followers. In television, which I write about, there are the famous Nielsen ratings, by which series live and die and careers are made or made redundant.

Even as the measurements and mediums change — Nielsen now also publishes Twitter rankings for television — the figures do seem to tell a simple, raw story. As a guide to corporate investment or disinvestment, renewal or cancellation, they might be useful. From a viewer’s perspective — and from a critic’s — they don’t matter at all.

Whether you are part of an audience of 1 million or of one, every transaction between artist and audience is roughly the same in its potential to be rewarding or disappointing. While it is nice to be part of some huge communal, contagious enthusiasm, whether it’s World Cup Fever or Weird Al Mania, you are always in a deeper sense on your own.

Although there has always been a range of possibilities and venues within the arts — from community theater to Broadway, from art-house films to summer blockbusters, from the Cinema Bar to the Fabulous Forum — modern technology has brought entertainment more than ever into line with this existential state of affairs. We now live in the age of the microaudience.

I learned long ago, in the trenches of punk rock, that many things I love are doomed commercially from the start and many things that succeed are as nails on a chalkboard. There is nothing I can do about this except to praise, patronize and promote the art I know I like, to share what seems beautiful or hilarious to me. That is why, for instance, I have written twice about “King Douglas,” a homemade cartoon series by teenager Wyatt O’Connell I came to by the usual way of clicking here and clicking there. The most-watched episode has been as of this writing “only” 1,570 times, as some would see it — and yet, 1,570 times!

Television was defined for many years by the products of three major broadcast networks. At the same time, outside of prime time, it was also highly regional — every broadcast station is locally operated, if not always locally owned — with programming that addressed local interests and a local audience. Just so, there was a time, before the mass media was as formatted and franchised as fast food, when a band with a Top 10 hit in Baltimore might have been entirely unknown in Chicago.

Now, even as the entertainment industry merges into fewer and fewer major players, we have entered a time of virtual regionalism, in which place is not defined geographically but by shared interest and aesthetic predilection, by the nodes of connection the Internet affords, and the kinds of communities it enables, as small as two like minds and as physically remote as half a world away.

Dozens and dozens of networks now produce original content, as broadcast and cable networks have been joined by streaming services connected to neither; add in independent posters to YouTube or Vimeo or Tumblr, whose ranks swell every day — and a small but significant fraction of whom are worth taking seriously — and the sum of what you could be watching becomes literally incomprehensible. You will never get your head around it.

Through these thickets of abundance, you make your own way, likely with a little help from your friends (actual friends, Internet “friends”), posting links on Twitter or Facebook, or even in actual conversation by a real water cooler. (Those things still exist, don’t they? I don’t get out much.) And it will be very much your own way; the days when half a nation might be watching the same TV show at the same time are gone. That is the argument for “à la carte cable”: Most of what you pay for, you’ll never watch; why not pay just for what you will?

Many complain about the dross Big Hollywood produces, the dreck that major networks air, the vacuity of big-time industrial pop music — products that require mass audiences to pay back their investment. And certainly there is a lot of money going to fund things that look like sure things that might, in some imagined ideal system resembling a rosy memory of the pre-”Star Wars”/”Jaws” 1970s, otherwise go to fund quirky, personal, downbeat works. But plenty of people like that stuff, which is why it gets made.

It is true that there are some kinds of movies you can’t make for less than $100 million, just as music recorded with expensive equipment in a finely tuned, purpose-built studio will have a different sort of quality than something knocked off on a laptop in a bedroom. But different doesn’t mean better, and it has often been the case that art made on limited means is what moves the culture forward, creates a new vernacular. (See: New Wave cinema, hip-hop music.) Experiment has always happened at the margins, where less money is at risk and a smaller audience required; that’s how Fox first distinguished itself from CBS, NBC and ABC and how cable distinguished itself from broadcast and Web-based video distinguishes itself from both.

Indeed, when I think back to the shows that have meant the most to me or just felt especially exciting in the moment — “Freaks & Geeks,” “Wonderfalls,” “Food Party,” “Bunheads,” “Incredible Crew,” “The Adventures of Pete & Pete” — many were not particularly successful or only as successful as they needed to be for their less demanding venues. These include recent Web-based enthusiasms “Danger 5,” “Bravest Warriors,” “Ghost Ghirls” and “The Future With Emily Heller.”

“Pancake Mountain,” now a feature of PBS Digital Studios, I first got into when it was a Washington, D.C.-based cable-access show available here only on DVD. Even a show like BBC America’s “Doctor Who,” a worldwide phenomenon, is a worldwide phenomenon among a particular audience; its American ratings are comparable to those of NBC’s finally canceled “Community,” whose audience was similarly devoted and narrowly defined.

Only 1,789 people donated money to fund Hal Hartley’s next film, “Ned Rifle” (premiering at the Toronto International Film Festival in the fall), though between them — or I should say, “between us,” as I am one of them — they managed to raise $395,292. This is slightly less than was raised last year to make the “Veronica Mars” movie (91,585 backers pledging $5,702,153) but enough to get it done on the terms Hartley set for himself. In this new economy, the shape of the work changes with the desire for the work the market will bear.

These are parlous times for creators. The digital connectedness that makes crowdfunding possible is also to no small extent what has made it necessary, devaluing content on the one hand (because there’s so much of it around, seemingly for free) and making it easier to steal on the other. We have a bad habit of regarding art as a form of recess for the people who make it.

The economics of major-league TV mean that, apart from loss leaders and executive pet projects, low-performing programs will die young, as the age-old difficulties of making a living drive creative people in all branches of the arts toward real jobs in the straight world. Nevertheless, we live in a time of abundance. If the old model of television is predicated on postponing failure — anything less than the 100 episodes thought necessary for a syndicated future — in the new one, the multi-platform video world I think of as “the televisions,” every new offering feels like a gift, wherever it might lead. Good gift, bad gift, that is for you to decide.

Does the fact that “Enlightened,” Mike White and Laura Dern’s HBO comedy about a spiritual half-awakening lasted only two seasons make it a flop? Or does the fact that 18 episodes of this beautiful show exist at all represent a triumph of the medium? White and Dern have their own, more complicated (and, I’m sure, more frustrated) answer, but from here, it’s all gravy.

Follow me on Twitter @LATimesTVLloyd

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.