Michelle Huneven on Christmas past and present

It’s become a tradition at the L.A. Times Food section: Every year we run a Christmas essay by a noted Southern California writer reflecting the unique nature of the way we celebrate the holidays. This year’s is by novelist Michelle Huneven, whose books include “Round Rock,” “Jamesland” and the most recent, “Blame,” all of which are set in the Southland. For many years, Huneven was also a regular contributor to the L.A. Times’ Food section.

I was so pleased to be asked to write this Christmas essay, I forgot that I am to a large degree Jewish — which was pretty much how everyone in my family always encountered Christmas, with a convenient amnesia.

My mother, a nonpracticing Jew from Delaware, had married a non-practicing Protestant in California. Sometimes, certainly not always, Jew + Protestant = Unitarian, and that is what we were — “Jewnitarians,” as I like to say.

Living in Altadena, attending public schools in the 1960s, we were swept up into the holiday mood. We had Christmas trees my mother called Hanukkah bushes, upon which little mesh bags of gelt (gold-wrapped chocolate coins) hung alongside metallic glass balls and colored lights. The crowning ornament was a star, in our case, six-pointed and blue. On Christmas Eve, we had a fire, invited both sets of grandparents and drank my mother’s vein-mortaring eggnog (cream, egg yolks and sugar), served to the adults with a glug of rum or brandy and a grating of nutmeg.

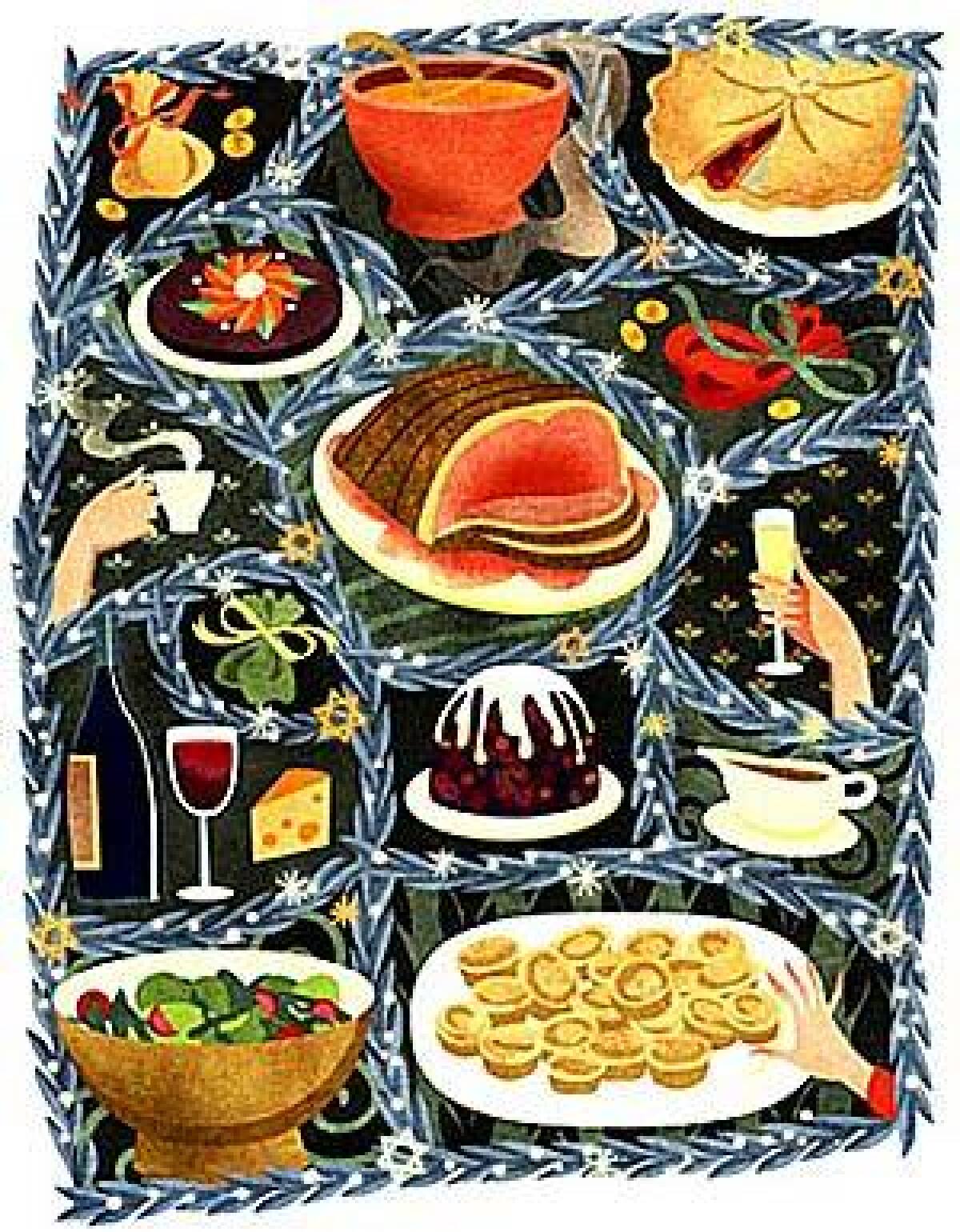

And Christmas Day brought a feast.

My mother started cooking as soon as the last present lost its wrapping. Prime rib, popovers and pie. The prime rib was served with horseradish cream, green beans, creamed onions, mashed potatoes or sometimes a noodle kugel, a big green salad, pumpkin and mince pies. The Protestants came to eat it, and, once my mother’s parents moved to Pasadena in 1959, so did the Jews. My mother was a terrific cook.

But she was an anxious cook, and her anxiety became palpable as the day progressed. My father was happy to be sent out for a pint of heavy cream. He stayed away longer than necessary. I hovered in the kitchen, enthralled. I trimmed beans, peeled potatoes, husked the creamer onions. I was ever careful, too, not to get in the way. My mother was juggling a lot of pots on the stove; her concentration was absolute and dangerous, a vibrating silence punctuated by the twang of the oven door hinge, the clatter of a pan lid, the breathy intake as the refrigerator door peeled off its seal, the eternal slow grind of our indoor rotisserie. After the pies were baked, potatoes mashed, the roast was resting, my mother poured herself a drink and waited for the last great cliffhanger of the meal: Would the popovers pop?

They did, mostly.

And if they didn’t — if they were squat, dense little plugs instead of great crusty bubbles, steamy and custardy within — only my mother (and I, her vigilant sous chef) really noticed.

I still love popovers with a great primal longing. Popovers signal an end to waiting, their successful ballooning still seems a small domestic miracle, a visitation of culinary grace.

But that was many years ago, when our family gathered at the dining table on those cool, crisp Altadena days, when darkness fell early, and we sat where we were told, when my mother finally relaxed, lulled by praise and bourbon, and my father carved the meat.

My mother cooked her last Christmas standing rib roast in 1987 and died a few weeks afterward.

Still, the holidays arrive rife with memories of her. I pass butcher counters and recall how she liked to scrape up and sample pan drippings for their concentrated beefiness, and how she’d pick at the crusty, salty bits off the roast, although at the table, she liked her beef “mooing.” My lifelong interest in food came from her. She collected the cookbooks put out by Sunset magazine, read them like novels before she went to sleep, dog-earing the recipes she wanted to try. I still cook out of her spattered, spine-busted “The Settlement Cook Book” whose subtitle is “The Way to a Man’s Heart”: The cover shows a long line of stout little aproned female cooks bearing trays of food to an enormous heart.

Christmas crowns the darkest time of year, which can also seem the loneliest. For two decades, single and childless, I cooked my way through the holidays (though not too deeply into any man’s heart). I so routinely baked cookies that the recipients started asking for certain varieties in advance. (Maida Heatter’s icebox walnut bars were especially in demand, as were my mother’s chewy crackled molasses crinkles).

For years, my friend Steve and I set aside one December day to make pork tamales, a 16-hour process that began at the masa factory in East Los Angeles and ended with tamales still steaming at midnight.

Nine years ago, I moved back to Altadena. And then I did the thing that would’ve made my mother happiest of all: I married a nice Jewish man.

And I agreed to celebrate the Jewish holidays.

And yet, and yet. Christmas persists in our lives, and we get swept up in it. For all the years of our marriage, we have Christmas Eve dinner with our friend Mona, whose children and assorted friends mirror my own mixed heritage. ( Santa Claus, when he clomps into the house, is a Jewish screenwriter.)

Every year, starting in early December, Mona and I start talking about what we’ll cook — although she pretty much has it down. The menu is a far cry from my mother’s meat-centric feast; the entrée is ricotta gnocchi with wild mushrooms from the “Sunday Suppers at Lucques” cookbook. It is my job to bring the salad and, some years, a dessert.

I cut fresh lettuce from my garden, coppery Quattro Stagioni, green Canary Tongue and Black-Seeded Simpson, all mixed in a red salad bowl. A simple olive oil dressing is made with juice from a neighbor’s Meyer lemons (ripe just in time!), my own homegrown garlic (and lots of it!), salt and pepper.

Here in Altadena, I have a beautiful old persimmon tree in the front yard. (Persimmon trees are sometimes called Christmas ornament trees because after all their leaves drop, dozens, even hundreds, of heart-shaped, coral-red ripe fruit, swollen to bursting, adorn the naked branches — and just in time for Christmas.) Some years, I’ve made the egg-, cream- and butter-rich, clove-haunted persimmon pudding from “The Joy of Cooking” (“The best thing I’ve ever eaten,” Santa Claus declared one year), although restraint lately inclines me more often to far simpler, calorically more austere persimmon cake.

For most of a decade now, a familiar crew has gathered in Mona’s kitchen, where the bustle of cooking proceeds apace even as we guests crowd in, pour Champagne and sparkling water, catch up on one another’s year. Mona is a generous, unruffled host. A spread of cookies is under steady siege from fly-by children while adults (and the more adventurous youths) spear lox onto sourdough flatbread, dip large boiled shrimp into horseradish-spiked cocktail sauce, crack fresh walnuts, imbibe. Meanwhile, wild mushrooms sauté on the stove. Bread crumbs toast in butter.

The homemade gnocchi are plunged into the enormous vat of boiling water and, as they start to surface, an old familiar tension starts to build in me — and I’m only a consultant here. But I can’t help it, cooking anxiety’s in my DNA. Will we get everyone to the table while the food is at peak heat? Are the gnocchi sticking together? Are the bread crumbs too brown? And doesn’t it seem that there may be too many of them?

Night falls, darkness gathers, candles are lighted, the lights on the tree blaze. The crowd in the kitchen starts drifting into the dining room. Someone uncorks wine. Someone else remembers to put water on the table. Miraculously, everything that’s supposed to happen happens: Enormous platters of gnocchi and salad are carried out to the buffet. We fill our plates, sit where instructed (or not), and set to.

Gnocchi. Salad. Pies, cookies and puddings. Coffee and tea.

We retire to the living room and shortly, clomp clomp clomp. Guess who?

On Christmas Day, my husband, Jim, and I walk, enjoying first the hush in the streets, which is broken shortly by kids out on new bikes, the sharp bang of a new basketball’s bounce.

Later on, around the same time that my mother’s popovers went into the oven, we’ll head down to Arcadia or San Gabriel, to Din Tai Fung or 101 Noodle Express, or Chung King, for Christmas dinner with the Jews.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.