The pull of the sequined vortex

There are certain inevitabilities to any figure skating competition. Plastic-wrapped flowers and stuffed animals will be thrown onto the ice. The audience will gasp at a botched triple Lutz, then break into mild applause for encouragement’s sake. A gangly teenager will perform to music from an opera in which the soprano is either stabbed or leaps to her death.

And, of course, there will be sequins, feathers, nude Lycra, draped velvet. And rhinestones. Thousands of them.

Never mind the prowess and guts it takes to land an axel. Many sports fans simply can’t see past skating’s aesthetic, which combines the flash of competitive ballroom dancing with the final scene of “Xanadu.”

In recent years, the more-is-more mantra has been particularly acute in the men’s competition. While top female skaters such as Yu-Na Kim and Rachael Flatt have struck a pretty and traditional tone with their costumes, theatrical garb that “tells a story” is en vogue among the guys, with designs that have no antecedent in modern fashion. Tailored masculinity, once the hallmark of the sport, is rare, if not downright passé.

Skaters used to be threatened with point deductions for outlandish costumes. Not so under the sport’s current scoring system, implemented after a judging scandal at the 2002 Winter Olympics. “I think a lot of male skaters see [embellished costumes] as part of the whole package, that it will enhance their marks,” says Evan Lysacek, a two-time U.S. champion. “Maybe it’s helping. If you don’t skate very fast, and you have a shiny outfit, it looks like you’re going faster. With a simple costume, you can’t hide behind much.”

But simple is what Lysacek prefers -- which makes him something of an outsider. On a recent afternoon at an El Segundo rink, he wore a Y-3 cashmere sweater as he skated through a group of young girls, who practiced layback spins and made no attempt to get out of his way. A veteran of the sport, Lysacek often wears Y-3 during practice. He has the tall, lanky proportions of a runway model, a Cartier watch collection and an affinity for the minimalist restraint of Raf Simons. At the World Figure Skating Championships, which begin today at Staples Center, you’ll see him attempt a quadruple toe loop wearing a shawl collar tuxedo with a rose tucked in the breast pocket.

“In my own clothing, I like simple, but something that has texture. Something that’s architectural and design-oriented,” the 23-year-old says. “That’s what I’ve looked for in my costumes as well.”

Three years ago, at the Winter Olympics in Turin, Italy, Lysacek skated to “Carmen,” one of the sport’s well-worn soundtracks. Instead of wearing a matador’s “suit of lights,” he opted for a black Gianfranco Ferré shirt with intricate pleating that approximated origami. He wore Alexander McQueen last season and fashioned a Christian Dior scarf into a belt the year before that.

“You have to dress up and have respect for the judges,” he says. “You can’t just skate in sweats and a cap. But who said anything about spandex and sequins?”

Actually, it was Johnny Weir, one of skating’s most reliably outré competitors.

The case for excess

Lysacek’s chief American rival for the last half-decade, Weir failed to qualify for this year’s world championships. But his imprint on the sport’s style is inescapable -- even if he’s not the first skater to wear a velvet onesie.

Weir’s influences, he says, are Russian skating greats such as Evgeni Plushenko, who never shied from a sparkly cravat. “To be accepted worldwide, American skaters need to understand that excess is necessary,” Weir says. “And yes, I take credit for that.”

His designer tastes are legendary -- Weir has modeled for Heatherette runway shows and dares you to try prying the Balenciaga work bag from his hands. But on the ice, the costumes he co-designs have a certain sartorial madness, much to his delight. At the Turin Games, he wore a shimmery swan costume, replete with a single red glove that he referred to lovingly in press conferences as “Camille.” Since then, he’s sported enough mesh, lace and rhinestones to exhaust the inventory of a crafts store.

“I’m a firm believer that if you’re a figure skater, you should wear a figure skating costume,” he says. “You can’t just wear all black and skate to Beethoven. There needs to be a story, and you’re the storyteller.”

Given their rivalry, you’d expect a clucked tongue from Lysacek when talking about Weir, but he’s surprisingly laudatory. “Johnny is his own person, and you have to admire that,” Lysacek says. “He’s like, ‘This is my style. This is the way I skate. This is my Louis Vuitton, and this is my fur. Deal with it.’ ”

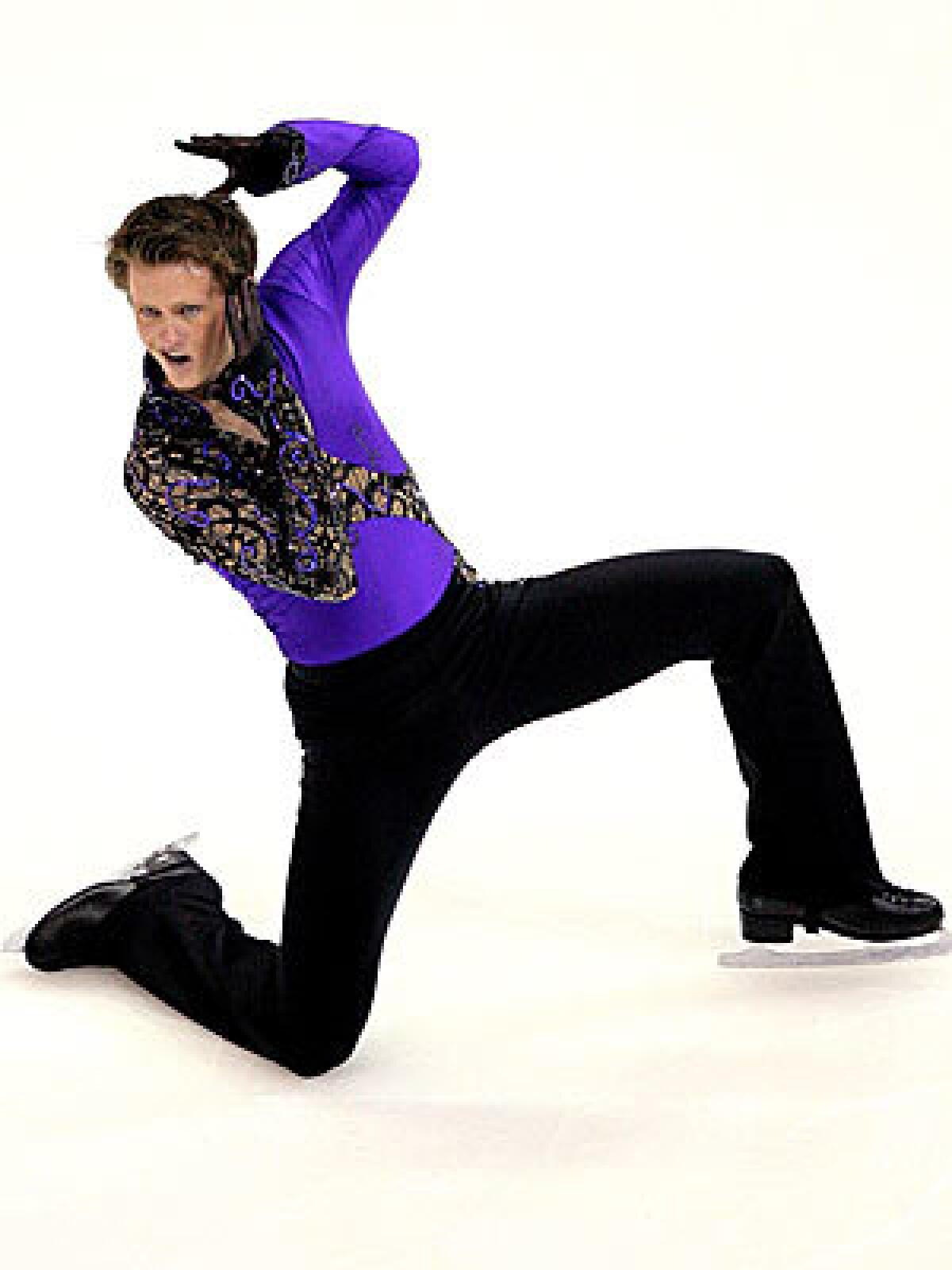

Jeremy Abbott, the reigning U.S. men’s champion and a rising star on the international scene, also has given in to glamour this season. He had asked Denver-based costume designer Joey Santos for a “fairly simple” long-program look. But what he got was something Weir might appreciate. Standing atop the podium in January, Abbott wore a violet Lycra top with black stretch lace that snaked across his torso, entangling his right arm. “I tend to like toned-down looks,” says Abbott, who trains in Colorado Springs, Colo. “So this is definitely the most puff and sparkle I’ve ever had.”

Black-tie skating

Men’s figure skating style hasn’t always been creative fodder for snarky screenwriters (think “Blades of Glory”). A century ago, competitors skated as if on their way to a black-tie gala. Forget rhinestones: If you wanted to express yourself, you did so with a superb flying sit spin, not a garish get-up.

Dick Button, the dapper, two-time Olympic gold medalist, performed Russian split jumps and flying camel spins in a waist-length white mess jacket for the 1947 World Championships in Stockholm. The color choice created a furor, he recalls. “Everyone said I looked like a waiter. Of course, all the skaters were wearing white jackets the following year.”

In the 1970s, stiff wool gave way to synthetic fabrics such as spandex, which made increasingly difficult jumps and intricate footwork possible. Perhaps spurred by growing television audiences and the popularity of exhibition tours such as the Ice Capades, many amateur skaters adopted a Vegas show mentality. By the 1980s, both the men’s and women’s competitions had become spectacles of jeweled décolletage and bedazzled unitards.

Not everyone approved of the excess. Scott Hamilton preferred athletic racing suits reminiscent of the ones worn by speed skaters. But judging by the fancy costumes in 1988’s “Battle of the Brians” between American Brian Boitano and Canada’s Brian Orser, Hamilton’s sporty uniforms failed to inspire other competitors.

By 1992, the U.S. Figure Skating Assn. had had enough. Judges threatened mandatory deductions for costumes that were “theatrical in nature” or featured exposed chests and “excessive decoration, such as beads, sequins and the like,” in the words of the organization’s rule book. Some male skaters summarily toned down their looks, and champions with subdued style, such as Paul Wylie and Todd Eldredge, ruled the American ranks.

The women held onto much of their sparkle, though some athletes tapped fashion designers for costumes that were runway statements, not rink extravaganzas. Nancy Kerrigan wore a gold, hand-beaded dress by Vera Wang, herself a former skater and a recent inductee into the U.S. Figure Skating Hall of Fame for costume design. Michelle Kwan, also a Wang muse, wore peach or royal purple sleeveless numbers with knotted backs for her performances to Puccini or Peter Gabriel.

‘Inner glitter bomb’

And then, little more than a decade after excess was labeled verboten, Weir let loose what he terms his “inner glitter bomb.” He’d long heeded the judges’ advice: Don’t go over the top, avoid theatrics. But after a disastrous national championships in 2003, he wrote off the American establishment, donned a Soviet warmup jacket and studied Russian. “At that point, I decided to do exactly what I wanted to do. So, next season, I came in like a firecracker,” he says.

And the formula has worked, he’s convinced, especially with international judges. Weir won a bronze medal at the world championships last year, though a poor performance this year at the U.S. nationals left him in fifth place. “A lot of these judges come from more culturally rich countries and understand the use of costumes to portray a mood, as in any opera, ballet or play.”

Today’s prevailing tastes often reflect the Russian coaches who now work stateside, says Tania Bass, a New York costume designer who has worked with Sarah Hughes, Irina Slutskaya and Abbott. “These are coaches who come from the real old world of costume making, and they don’t lose their flamboyancy in the U.S.,” Bass says. “For a while, it was turning into a fashion show. Now it’s strictly costume. I don’t know which is best -- I just love to see an elegant skater.”

Button is also ambivalent. “I love the freedom in the sport. You can do almost anything today,” he says. “But yes, I’ve got to tell you that some costumes are just overboard. And I’m not sure why there are crosses on everything these days.”

He may be referring to Lysacek’s costume for the short program Wednesday. Though the skater is tux-clad for his free program, Lysacek trained in St. Petersburg over the summer with a Russian choreographer, who chose a costume with a glittery cross adorning the front. Lycasek knows to pick his battles. “It’s part of her vision, and it’s definitely pushed my comfort zone,” he says with a hint of amusement. “But the long[-program] costume she sent was originally head-to-toe sequins, giant billowy sleeves with pure black crystal. That I had to change.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.