Review: Yayoi Kusama at the Broad: Lots of mirrors, not so much artistic reflection

Yayoi Kusama turned 16 just a few months before two atomic bombs were dropped on Japan, obliterating first Hiroshima and then Nagasaki. Those horrific events in August 1945 were — and remain — the world’s only episode of nuclear warfare.

Kusama lived with her family in Matsumoto, a little over 400 miles to the east, which might be like living in Los Angeles if San Francisco were to get atomized. The impact, psychological and emotional, would be profound.

Obliteration has been a theme in Kusama’s art since her marvelous abstract “net” paintings, begun in the late 1950s. It also drives the popular mirrored rooms that are among her least significant works. What works for the paintings doesn’t for the sculptures. Six of the 20 rooms she has made since 1965 anchor “Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors,” a new exhibition at the Broad museum.

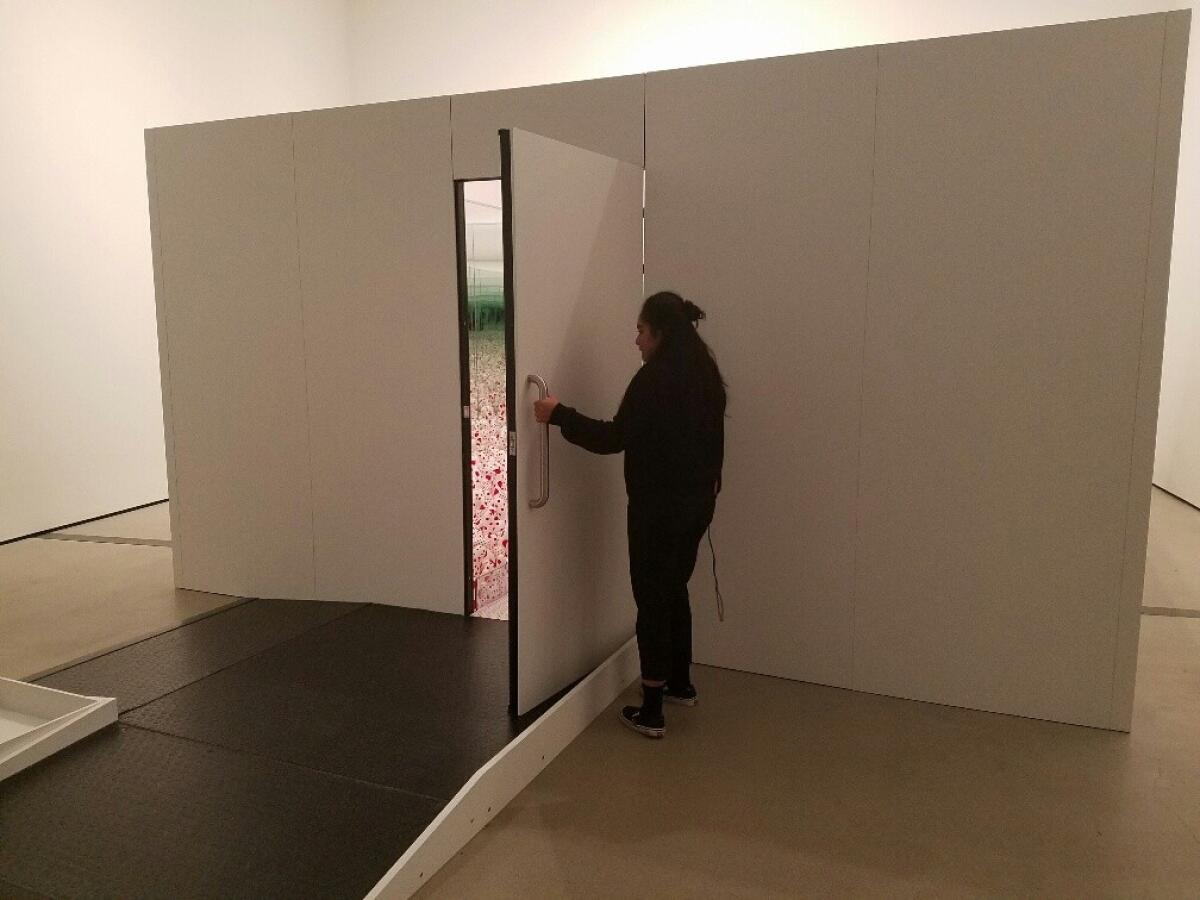

The first room is “Phalli’s Field,” a work no longer extant but re-created last year for the traveling show, which was organized by the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. Fifteen feet square and 8 feet high, the re-created white room is a self-contained gallery for one person at a time.

Inside, the floor is chockablock with white phallic pillows covered in red polka-dots. This Surrealist ensemble is reflected in surrounding mirrored walls, extending it into a vast, visually endless field.

When Kusama made the original version, she had been living in New York for about seven years. Second-wave feminism and the sexual revolution were gaining steam. (The U.S. Supreme Court had just struck down the only remaining state law banning the use of contraceptives by married couples.) The mirrored room’s playful sea of erotic forms was far tamer than an audacious work like “Meat Joy,” Carolee Schneemann’s filmed Dionysian celebration of flesh as an artistic material. The phallus-room was in the ballpark of rebelliousness, but today it seems quaint.

So it goes through all of Kusama’s rooms, the most recent from 2016. Her mirrored environments house blinking white and colored lights, inflated pink spheres with black polka dots and orange fiberglass pumpkins lined with more polka dots. Sometimes the mirrors are black, heightening dramatic contrast. The show positions them as her breakthrough, but they feel more like the beginning of the end.

“The Obliteration Room” is one with no mirrors. It’s an all-white interior – an open-concept living and dining room in which visitors are invited to put random, multicolored stickers on every surface. As attendance swells and dot-stickers proliferate, a blank domestic space is essentially transformed into a walk-in bag of Wonder Bread.

There has been some grumbling that visitors are allowed no more than 30 seconds inside each mirrored room. (Pricing is $25 for advance-ticketed admission, already sold out, or $30 for a limited number of tickets at the door.) An attendant with a stopwatch politely scoots you out when your time is up.

Yet, it turns out that 30 seconds is too long, not too brief. Inside, there’s simply not much to see.

That might explain why “Infinity Mirrored Room — Love Forever” (1966/1994) is the strongest work. You cannot go inside it. Small porthole windows open onto a sealed, light-dotted chamber within, so you enter only with your eyes. Linger as long as you like, while tiny colored lights dance in psychedelic patterns.

Peep shows are always mysterious — and doubly so when you can catch a glimpse of another viewer peeping in through a window across the way, infinitely reflected. Being alone peeping while in the presence of another is a strangely giddy experience.

Selfies taken inside the mirrored rooms are all over Instagram and other social media. The most interesting feature of the rooms is that looking at the ubiquitous photos of them is as fulfilling as actually being there — which may be a first for art. (It may also relieve those unable to snare tickets to the show.) Small surprise: Kusama turns out to be an unwitting pioneer of art fabricated to be photographed.

For context, the survey also includes biographical ephemera — posters, show announcements, documentary photographs — plus a few “accumulation” sculptures (furniture covered with more stuffed phalli). Recent abstract paintings and sculptures are brightly colored, child-like doodles enlarged to public scale; loud but empty, they’re among the dullest paintings and sculptures you’re likely to encounter in an art museum this year.

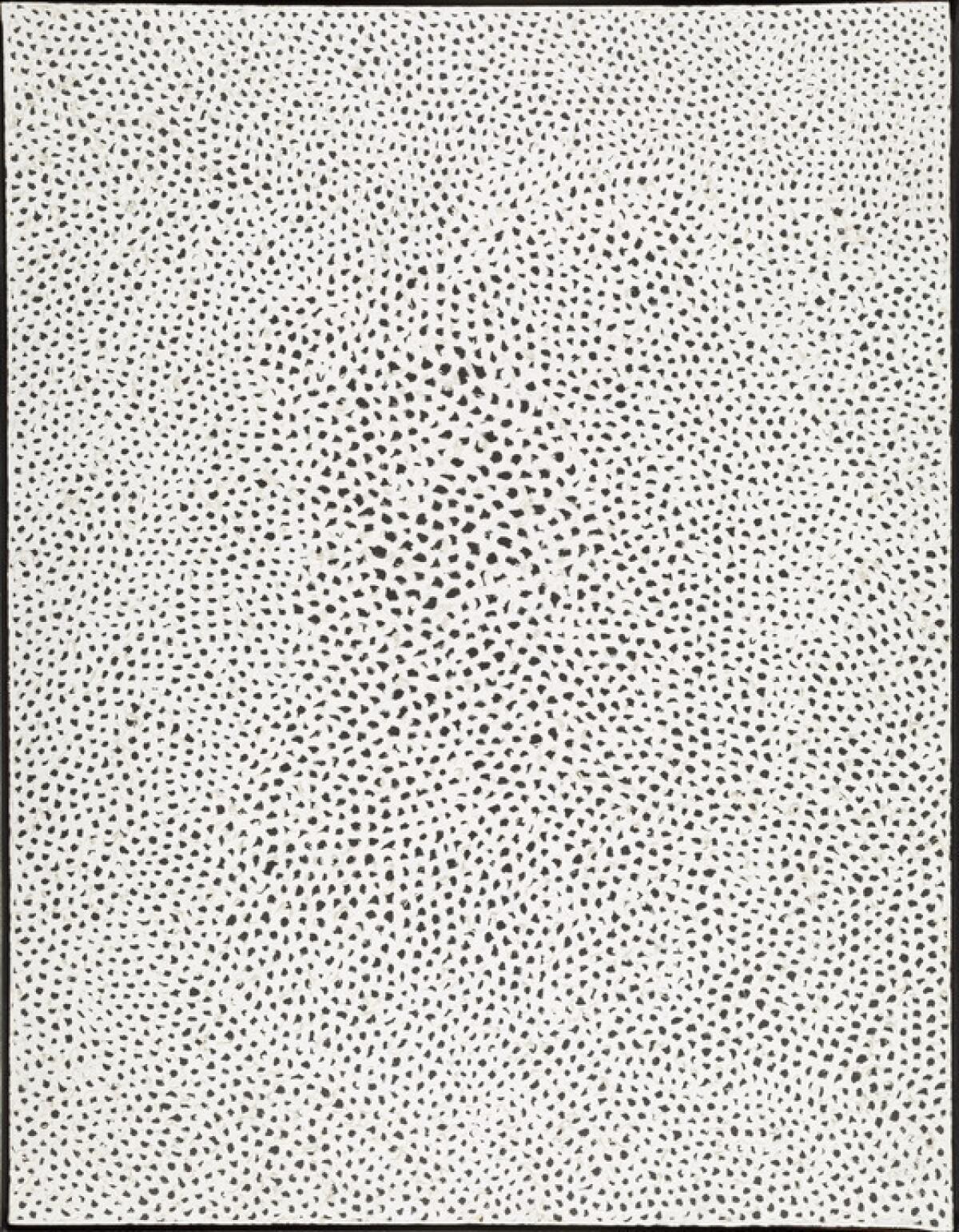

For Kusama, obliteration means eradicating an individualistic sense of self, allowing it to be absorbed into an amorphous, universal infinity. It’s the opposite of an insistent, expressive self, which characterized male-dominated Abstract Expressionism.

The sentiment is most compelling in her 12 meditative “net” paintings, evolving in a dozen drawings from the late 1950s and early 1960s. (The “nets” also stood out in a 1998 Kusama retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; she still makes them, although only one from after 1961 is here.) Row upon row of linked brushstrokes create textured, monochrome comma-shapes atop a flat, contrasting monochrome surface. The handmade pattern resembles the scales of a fish.

Painterly gesture is often a uniquely dramatic sign of inner emotion, but ritual repetition lets the steam out. And unlike Abstract Expressionism, painted with the big motion of an artist’s arm and wrist, the nets are painted intimately, using fingers and knuckles.

Your eye is propelled along, your mind grouping optically unexpected shapes from clusters of linear loops; the shifting shapes constantly fall away and then regroup, only to fall away again. Phantom colors emerge, then disappear. Obliteration is perceptually enacted in experiencing the paintings; in the mirrored rooms, you merely witness its depiction.

At the busy preview when I saw the show, the two galleries of net-paintings and drawings were mostly devoid of other people. Their potential as a selfie backdrop is limited. You’ll have plenty of time to experience the great net paintings — and not just because there’s no 30-second rule.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors’

Where: The Broad museum, 221 S. Grand Ave., L.A.

When: Through Jan. 1; closed Mondays

Tickets: Admission to the museum is free but requires a timed ticket; admission to the Kusama exhibition is $30. Read the Kusama ticket FAQ.

Info: (213) 232-6200, www.thebroad.org

christopher.knight@latimes.com

MORE ART NEWS AND REVIEWS:

Video: Inside Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms

Explainer: How the mirrored rooms work

Alejandro Iñárritu's virtual reality art installation wins a special Oscar

Can 11th-hour updates save Renzo Piano's design for troubled Academy Museum?

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.