2 sides at odds over plight of activist-kidnapping suspect in Mexico

Nestora Salgado, a Mexican American woman who returned home to the violent state of Guerrero to run an ad hoc community police force and whose clashes with local authorities landed her in prison, may soon be freed.

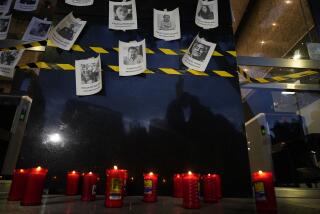

Something of a cause celebre in parts of Mexico and the U.S., Salgado has languished in a Mexican federal prison for a year and a half after her arrest on charges of kidnapping. The accusations, she and her supporters say, stemmed from the community police force’s arrest of six people tied to a violent drug cartel in their hometown of Olinala, high in the Guerrero mountains.

Yet even as Salgado’s liberation appeared nigh, a campaign opposing her release has gained steam, painting a much darker picture of the jailed community leader’s activities.

Was she, as has been widely reported, a courageous and charismatic activist who used her U.S.-honed skills and sense of justice to challenge the corrupt politicians and brutal police, in cahoots with drug traffickers, who were terrorizing her hometown?

Or, was she, as a group of activists claims, one more Guerrero thug, a ruthless abductor of dozens of people from whom she extorted ransom money?

Rogelio Ortega, the recently appointed governor of Guerrero, appears to side with the first version. Last week, he instructed judicial officials to drop the case against Salgado.

The people of Guerrero demand “the immediate freedom of political prisoners and prisoners of conscience,” Ortega said in announcing his decision in the Salgado matter.

He placed his decision in the context of forming a “citizens’ government” that he said would seek peace, harmony and the preservation of human rights in one of Mexico’s most conflict-ridden and impoverished states.

Ortega in October succeeded Gov. Angel Aguirre, who was forced to resign after the kidnapping and apparent massacre of 43 college students on Sept. 26. Aguirre had been one of the movers behind the arrest of Salgado.

Now in her early 40s, Salgado spent 20 years in the United States, mostly in the Seattle area, where she worked, built a life and raised three children after leaving Guerrero. She holds dual U.S.-Mexican citizenship.

After returning to Olinala to stay a few years ago, Salgado helped lead a town rebellion against criminals who were killing taxi drivers, dealing drugs and extorting protection money from local businesses, her supporters say. Soon she formed and took charge of a vigilante squad, which her supporters say was allowed under a special law for Guerrero that permits indigenous community policing.

Salgado ran afoul of powerful local politicians, however, when she arrested three teenage girls accused of peddling drugs and then a well-connected City Hall official and two buddies she accused of stealing a cow. All were sent to an ad hoc detention center in another city.

It is those people, along with several others who also ended up at the detention center, who are now claiming that Salgado kidnapped them, said Isabel Miranda de Wallace, head of an organization called Halt Kidnapping.

“We do not know if Mrs. Salgado is innocent,” Miranda said during a news conference this week, “but what we do know is that there are victims who are asking for justice.”

She said the Guerrero governor is overstepping his authority by seeking Salgado’s release and that the case must be allowed to run its course in Mexico’s haphazard judicial system.

“What Guerrero needs are the [proper] legal channels and for a judge to be the one who determines whether Mrs. Salgado is innocent or guilty,” Miranda added.

Samuel Gonzalez, an attorney and former federal prosecutor who works with the anti-kidnapping group, said the Salgado affair shows the lack of rule of law in Guerrero, and that freeing her without adjudicating the case would only further that vacuum.

“At the very minimum,” Gonzalez said in an interview, “you have to approach and negotiate with the victims.”

“There are no ‘victims!’” responded Salgado’s husband, Jose Luis Avila, speaking in a telephone interview from his home in a suburb outside Seattle. The “victims” were people who had broken laws and were under arrest, Avila said.

“Her actions touched powerful people, and they are who is behind this, people who don’t want her to get out,” Avila said. “She would tell things like they are. She was always the pebble in their shoe.”

A human rights network of mostly female activists on Wednesday denounced what it said was a telephoned threat to Salgado’s daughter, Saira. “Pray to God that your mother stays where she is, or you and your little angels will pay the consequences,” the voice said, according to the organization.

Leonel Rivero, Salgado’s lawyer, who took the case three weeks ago, said he has found six additional pending charges involving kidnapping and robbery that were never included in the original investigation and can be revived now as a way to keep Salgado in prison.

“The case is much more complicated than what had been thought,” he said in a telephone interview from Tlapa, a city in Guerrero.

A hearing for Salgado and several of the people who say they were kidnapped has been scheduled for later this month at the federal prison in the western state of Nayarit where Salgado is being held, Rivero said.

Even some of Salgado’s supporters acknowledged she probably went too far in dispatching detainees off to another city and to a center run by fellow vigilantes, where some spent several months until the army rescued them.

Under the community policing rules, the ad hoc defense squads are supposed to hand suspects over to mainstream police or other authorities. Salgado’s squad members say, however, that each time they did that, the local authorities would immediately free the suspect.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.