Capitol Journal: Brown, Legislature serve up a leaner budget

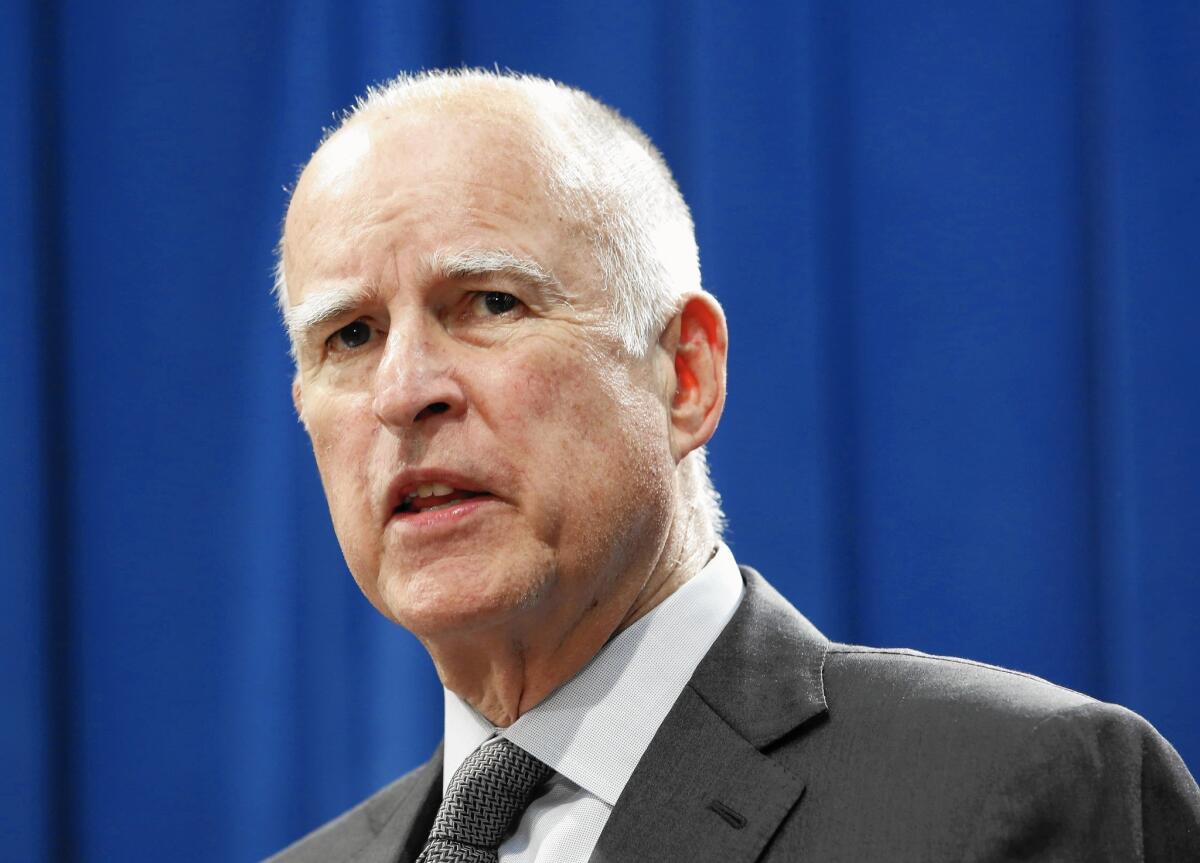

Gov. Jerry Brown was eager to put the budget fight behind him and move on to two nagging dilemmas: raising enough money to repair California’s deteriorating highways and to heal Medi-Cal.

The Legislature sent Gov. Jerry Brown a ham sandwich Monday and it was quickly cooked into a low-fat, full-course meal.

It was much more nourishing than the bologna legislators used to serve up summer after summer.

I’ll need to explain that.

Back in the bad old days, California was one of only three states that required a two-thirds legislative vote to pass a budget. Too often, lawmakers spent much of the summer embarrassing themselves and the state while failing to pass a budget.

In 20 out of 32 summers, a budget wasn’t passed until after the fiscal year began July 1, usually long after. Eight times it didn’t pass until at least August.

Finally, in 2010, voters passed a ballot initiative allowing a budget to be OKd by a simple majority. It included a sweetener for voters: Legislators would lose their pay if they didn’t approve a balanced budget by June 15.

The next year, legislators passed a gimmicky spending plan by the deadline. Brown quickly vetoed it, calling the proposal unbalanced. And state Controller John Chiang refused to pay them.

The Legislature sued. Chiang’s lawyer told the judge that “you could take a piece of paper and write [some numbers] and you could wrap it around a ham sandwich and you could send it over to the governor, and you could call it a budget.... But it’s still a ham sandwich.”

But the judge sided with the Legislature, essentially ruling that the constitutional separation of powers allows it to call even a ham sandwich a balanced budget.

So that’s legally where legislators stood Monday, the deadline. Any “budget” they passed would keep their pay flowing.

Truthfully, it wasn’t a bad budget. But it had too much fat for the governor. With Brown controlling the kitchen, the two sides turned out a compromise within 24 hours.

Why couldn’t they have agreed last week? A reporter asked Brown that question Tuesday and he answered: “Well, why things are the way they are is a very philosophical question that I think you should ponder.”

OK, my pondering tells me that legislative leaders wanted to show they couldn’t be pushed around. “This is not rule by fiat,” Senate leader Kevin de León (D-Los Angeles) declared during the Monday budget debate. “This is not a monarchy.”

And Brown again wanted to look like the tough guy on spending. “At the end of the day,” he told reporters, “it’s my job to keep this budget on an even keel.”

Brown, of course, is focused far beyond this budget to the one he’ll leave his predecessor in 2019. “When governors leave town with big deficits,” he observed last month, “they’re more scorned than praised.” Brown knows; he left a fiscal mess when he was governor the first time.

Brown was asked exactly when the budget deal was cut and what were the key elements. He replied with a typical Brownism: “It’s not like a moment in time. It’s a gradual unfolding of deeper understanding.... It’s an iterative process.”

The real answer: After midnight on Tuesday. And the governor tossed in some sops to Democrats on child care and preschool, state universities, in-home services and dental care for the poor.

Both sides wanted to provide healthcare for immigrant children in the country illegally, and did. Same with the state’s first earned-income tax credit for the working poor.

Brown insisted on using his own revenue projections, which were about $3 billion under the Legislature’s. The $115-billion general fund spending compromise was roughly $2 billion below what the Legislature had passed and only $61 million more than the governor had proposed.

Brown rejected the Democrats’ attempts to raise welfare payments for mothers when they have another child, allow home child-care workers to unionize and to boost grants for the aged, blind and disabled who are drawing the federal minimum.

“That’s a heartbreaker,” De León told me concerning the failure — again — to provide more money for the politically weak aged and disabled. “I’m going to fight for that next year.”

Brown was eager to put the budget fight behind him and move on to two nagging dilemmas: raising enough money to repair California’s deteriorating highways and to heal Medi-Cal, the healthcare program for the poor.

To his credit, the governor has decided to prioritize fixing roads and bridges. Congress should act too, he said. “The federal government has its collective head in the sand.”

Problem is, automobiles have become so fuel-efficient that motorists are burning less gasoline. So the gas tax isn’t paying off as envisioned. Brown says it’s generating $2.3 billion annually for maintenance and repairs, but an additional $5.7 billion of work is needed.

Highway upkeep “has been bedeviling this state for the last three governors,” Brown said. “So we’ve got to get at it.... Hopefully we’ll get something fairly quickly.”

One of the problems facing Medi-Cal is that more people are eligible because of Obamacare. But state provider rates, already the lowest in the nation, were chopped further during the recession. So there aren’t enough doctors willing to serve patients.

Fortunately, because of the budget vote reform, legislators can spend the summer debating highway and Medi-Cal funding. Democratic leaders won’t need to grovel to Republicans, trying to buy their budget votes by offering to fund pet projects.

That often produced worse than ham sandwiches. It cooked up rancid pork.

Twitter: @LATimesSkelton

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.