With only one left, iconic yellow road sign showing running immigrants now borders on the extinct

So many immigrants crossing illegally into the United States through California were killed by cars and trucks along the 5 Freeway that John Hood was given an assignment.

In the early 1990s, the Caltrans worker was tasked with creating a road sign to alert drivers to the possible danger.

Silhouetted against a yellow background and the word “CAUTION,” the sign featured a father, waist bent, head down, running hard. Behind him, a mother in a knee-length dress pulls on the slight wrist of a girl — her pigtails flying, her feet barely touching the ground.

Ten signs once dotted the shoulders of the 5 Freeway, just north of the Mexican border. They became iconic markers of the perils of the immigrant journey north. But they began to disappear — victims of crashes, storms, vandalism and the fame conferred on them by popular culture.

Today, one sign remains. And when it’s gone, it won’t be replaced — the result of California’s diminished role as a crossing point for immigrants striving to make it to America.

For all the often vitriolic talk about illegal immigration, debates about sanctuary cities and President Trump’s promise to build a massive — and “beautiful” — wall along the southern border, few places have seen the generational decline in illegal crossings like California.

In 1986, the San Diego sector recorded its highest number of border crossing apprehensions in a year: 628,000, according to Department of Homeland Security statistics. The area — geographically the smallest for Border Patrol — was once the busiest sector for illegal immigration in the U.S., accounting for more than 40% of nationwide apprehensions in the early ’90s.

In fiscal year 2016, Border Patrol agents apprehended 31,891 people in the San Diego sector suspected of crossing the U.S.-Mexico border illegally.

And so the famous border crossing sign, Caltrans officials say, has become largely obsolete.

Over the years, the signs took on a fame and meaning that belied the utility that inspired them — popping up in TV shows and movies, in street art and T-shirts.

In 2011, British street artist

Student immigrant rights activists adopted the sign as their logo, adding graduation caps, gowns and diplomas to the characters. Other parodies depict the characters wearing Pilgrim hats — a message intended to convey that

Those opposed to illegal immigration re-imagined the signs, depicting the family as a threat, with the man brandishing a rifle.

A photograph of the sign hangs at the National Museum of American History, part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

A generation after they were installed, the last of the “running immigrants” signs stands on two wooden posts in a concrete median of northbound Interstate 5, just before a “Welcome to California” sign.

Remnants of a broken taillight, a tattered ice cream wrapper and a couple of resilient weeds speckled the ground around it on a recent day. Cars and trucks whizzed by on the windy freeway. Motorists quickly accelerated after hours of waiting in congested traffic to cross into the United States.

In the 1980s, more than 100 people were killed as they tried to cross freeway lanes in the San Ysidro area and between San Clemente and Oceanside. Caltrans wanted to do something about the problem and asked Hood, a California Department of Transportation employee and Vietnam War veteran who grew up on a Navajo reservation in New Mexico, to come up with a sign that would alert drivers and could reduce the number of deaths.

He eventually settled on using the image of a family in an effort to tug at the heart in a way a typical road sign might not. A little girl with pigtails, he thought, would convey the idea of motion, of running.

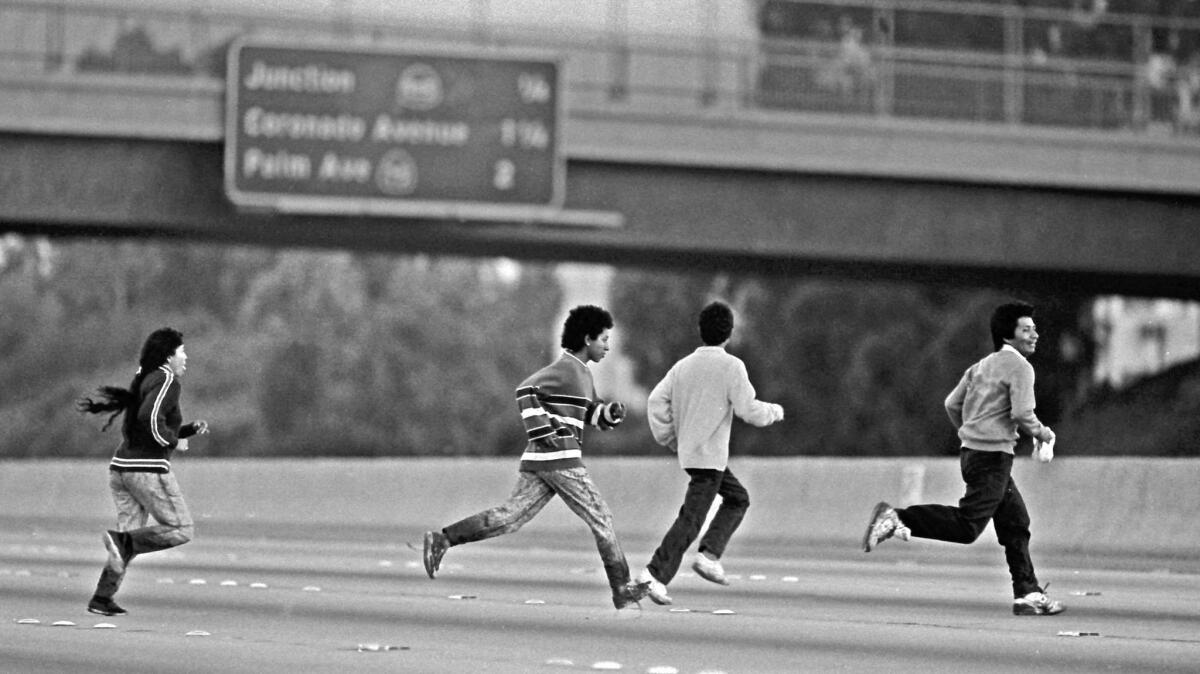

The sign was inspired by photographs of people crossing at the time, including those taken by former Los Angeles Times staff photographer Don Bartletti.

Caltrans first installed the signs in late 1990 and early 1991. After workers erected a median fence along the freeway’s trouble spots in 1994, officials decided not to replace any future signs that were lost. Around that time, federal officials launched Operation Gatekeeper, which fenced off the U.S.-Mexico border in San Diego — pushing illegal immigration east, toward Arizona and Texas. That helped reduce the number of freeway-crossing deaths, Caltrans officials said.

“You create your work, and that’s the extent of it. You never envision something like that to happen,” Hood said about the sign’s evolution. “It’s become an iconic element. It lives on.”

Estela Dutra, a hairstylist at Selena Estetica Unisex on West San Ysidro Boulevard, said she always found the signs offensive. The image is akin to a cattle crossing, she said.

“It’s sort of humiliating, dehumanizing. It makes us look like animals ... primitive people,” she said.

The 72-year-old, a naturalized U.S. citizen, illegally crossed the border 40 years ago. She entered with ease as a car passenger along the San Ysidro crossing, she said.

“I wasn’t asked for a passport or a visa,” she said. “Can you believe it? Those were different times.”

Dutra said she gets teary-eyed when she sees the remaining sign on her way north from a day trip to Mexico. Her sadness doesn’t stem from her journey so long ago, but for those who continue to make the trip — which has become increasingly treacherous.

“I just feel so much sadness for all the families that have to go through that. Can you imagine how much they suffer?” she said. “The families that cross leave everything behind — the little they have — and risk it all.”

So many immigrants and smugglers once illegally crossed the border here that Obdulia Morales tried to bar their passage along her Mexican restaurant with an iron gate.

Don Felix Café’s narrow-bricked alleyway, a little over a mile north of the southern U.S. border along West San Ysidro Boulevard, had become a perfect hiding spot for smugglers and the smuggled.

Morales, who dished up mole and menudo on a recent day, said it was a complicated time and business was booming. Back then, many shop owners knew who dabbled in human smuggling even as they served immigration enforcement agents who packed the border region.

“Border Patrol agents would come and eat here all the time,” she said, noting that smugglers did too.

As for the yellow caution sign, Morales said she almost had forgotten about it, even though the last one is not far from her diner.

At the time he drafted the sign, Hood said he didn’t imagine his creation would take on a life of its own.

“I think that I was more amazed by it,” he said. “I’ve seen it in so many places.”

Hood recently spotted the sign in an episode of the AMC zombie series “Fear the Walking Dead” — which takes place on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. “Wow,” he thought.

Although the warning sign won’t be replaced, it will live on as a symbol of California’s not-too-distant past, when the front lines of the country’s battles over illegal immigration lay in the Golden State.

Hood, who still lives in San Diego after retiring from Caltrans, said he took his son and daughter to visit the last sign about three months ago after realizing it was the only one left. They snapped photographs.

Turning to his son, Hood said, “It’s served its purpose.”

Follow Cindy Carcamo on Twitter @thecindycarcamo

ALSO

Trump, in meeting with Mexican president, again insists Mexico will pay for the wall

Malnourished 5-year-old found in chains in Mexico may be returned to U.S.

Months after deportation, they do what the Mexican government will not

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.