Great Read: Activist L.A. priest follows religion of acceptance

Armed with a bottle of water and a baseball cap, Father Richard Estrada made his way slowly to the border in the scorching heat. After a half-hour of hiking up a steep dirt trail, he reached the massive steel fence and bowed his head to pray for the immigrants who dreamed of passing it.

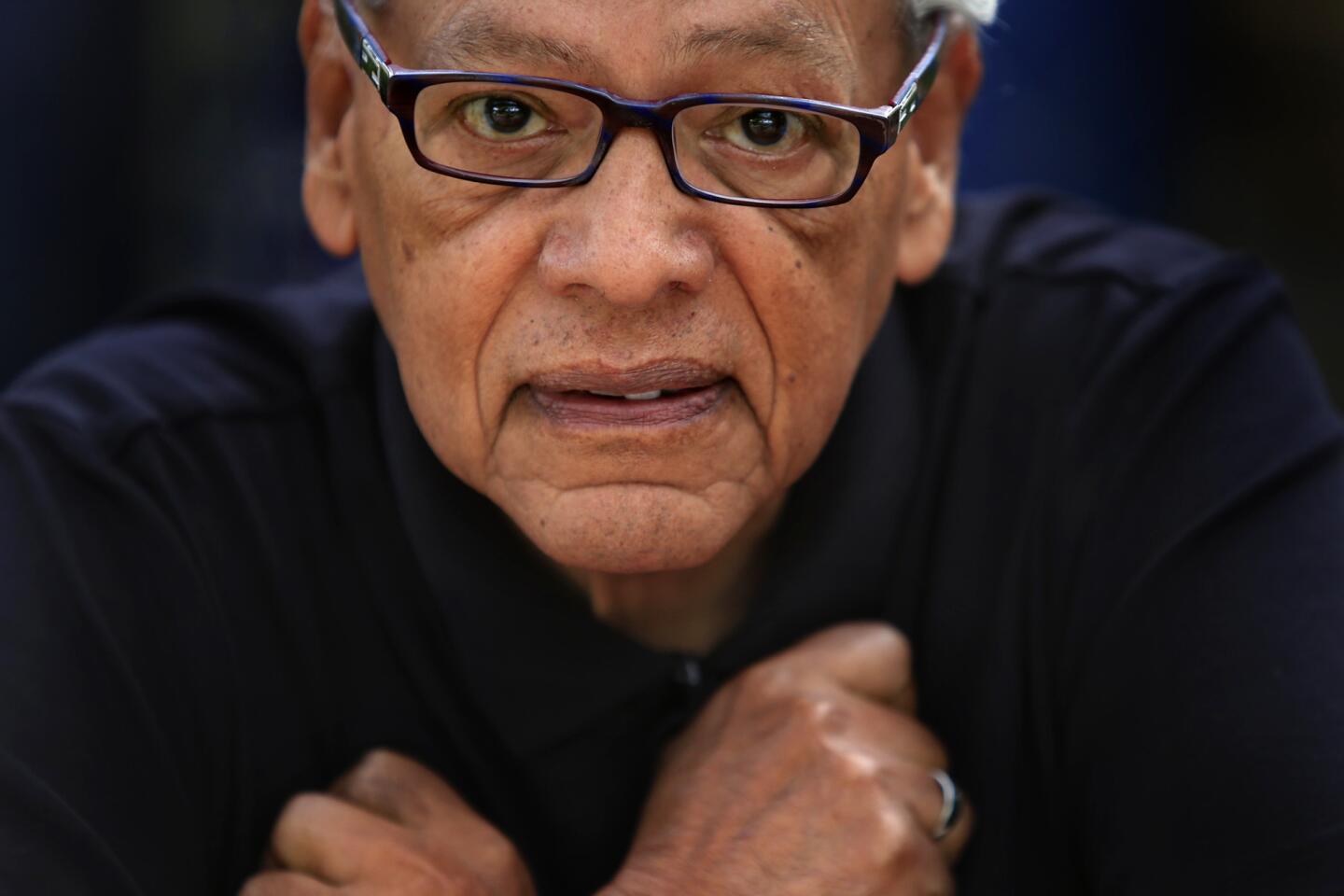

Estrada, 72, had had cataract surgery the day before. Arthritis made his legs ache. But the priest wasn’t one to let anything — not even his aging body— stop him from doing what he felt was spiritually right.

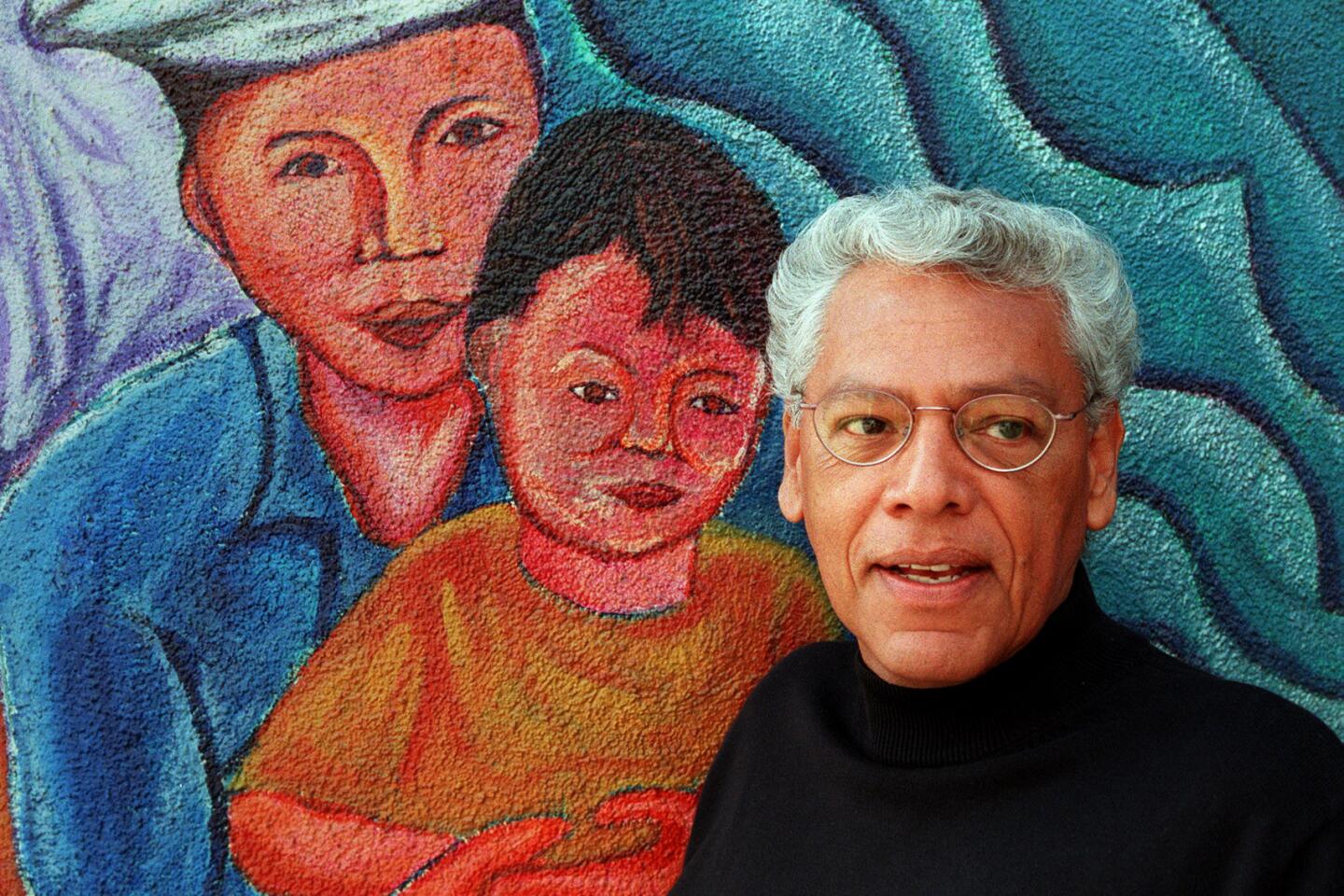

On this day, he wore his snow-white hair tied back into a ponytail, and a colorful stole around his shoulders. When he became a Catholic priest in 1978, he sported a handlebar mustache and combed his wiry black hair into an afro. Cesar Chavez, whom Estrada had befriended while leading grape boycotts in East Los Angeles, was a guest at his ordination ceremony.

It was an apt start for an activist priest who would become a fixture of the L.A. liberal scene and a fierce advocate for immigrants.

At La Placita, the little downtown church where he ministered for years, he helped plan the historic immigration march of 2006, which drew hundreds of thousands of people to the streets.

He founded the city’s first homeless shelter geared toward immigrant youth, and was long at the forefront of the sanctuary movement, sometimes angering immigration authorities by offering his church as a refuge for those facing deportation.

Central to his spiritual outlook is the concept of la posada — the Spanish word for inn, or lodging.

“I’m into giving shelter,” he said in an East L.A. accent.

In recent years, Estrada struggled to square that ethic with elements of Catholic doctrine that he felt were unwelcoming, particularly attitudes toward gays and lesbians, and limits on leadership roles for women.

So on this hot August morning, as Estrada headed to the border with a group of religious leaders from the U.S. and Mexico, he shared some news:

“I’ve moved to the Episcopal Church.”

::

These days, Estrada’s base is the small stucco home near Montebello that he inherited from his parents. A fountain bubbles in the flower-filled courtyard. Inside, a television tuned to CNN often plays in the background.

In his bedroom, a poster that says, “Proud member of the religious left,” looms next to a portrait of the Virgin of Guadalupe. On a recent morning, his 2-year-old pit bull, Honey, was quietly gnawing on a Bible on the bed.

For decades, Estrada saw the pain of gay and lesbian parishioners who were ashamed of their sexuality, and of women who he felt were treated as second-class citizens. He saw the Catholic Church evolving on those issues, but the changes felt too slow.

“I saw a lot of people who were struggling,” he said. “I just felt like I don’t fit anymore. Maybe I’ve grown, or shrunk or whatever, but I just don’t fit. And I haven’t fit. So let’s be honest.”

In 2013, he told his superiors of the Claretian Missionaries that he was leaving, and last year he joined the Episcopal Church, in part because it allows women, gays and lesbians to serve as priests and bishops.

“I should be retiring, not starting a new career,” he said, smiling as he puttered around the kitchen. “But I had to be true to myself. God is putting me places. He or She is in charge.”

Last year, Estrada had planned to take a sabbatical, a time for reflection as he waited for news on whether the Episcopal Church would give him a congregation. But then tens of thousands of children started showing up at the border fleeing an increase in violence in Central America. Estrada kicked into gear.

He traveled to Tapachula, Mexico, along the Guatemala border, where he marched to raise awareness about the plight of young immigrants. Back in L.A., he attended meetings at City Hall and with the heads of local nonprofits to map a plan to provide social services for the children.

In the fall, a woman he had met at a homeless shelter in Mexico called and said she and her three sons had made it across the border and to a shelter in Long Beach. He picked the family up and took them to the barber for haircuts and to Target for new clothes.

That evening, they drove to a Mexican restaurant near downtown, where Estrada was hosting a “Holy Happy Hour” fundraiser for the Tapachula shelter. It was one of the boys’ birthdays, and a crowd cheered as he blew out candles on a cake.

The recent flood of young immigrants feels “like deja vu,” Estrada said.

In the 1980s, he and the other priests at La Placita, the nickname given to Our Lady Queen of Angels church, opened the chapel to hundreds of Central American refugees fleeing civil war.

It was a heated time in the immigration debate, with federal authorities accusing the priests of encouraging illegal behavior. Estrada responded by doubling down, handcuffing himself to a federal immigration building to call for the release of those in detention. He was arrested — the first of four times that he would be detained for civil disobedience.

Maria Elena Durazo, the former head of the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, who has appeared alongside Estrada at countless demonstrations, said the priest has always identified with those without power.

“He doesn’t see himself as the face of the establishment,” Durazo said. “He sees himself as the face and the voice of the believers.”

::

For all his bold activism, Estrada is a gentle presence, more comfortable listening to others than talking about himself.

Listening is a skill he acquired during his first career as a hairstylist in East L.A., where he would sometimes hear female clients recount stories of hardship and abuse.

It was, in part, out of a desire to help them that he decided to take a cousin’s advice and join the seminary. Estrada said his cousin, a nun, had something that appealed to him. “She was so at peace,” he said. “I wanted that.”

While performing Mass, marriages and other priestly rituals, Estrada helped lead an effort to deliver thousands of gallons of water to the desert along the border, where immigrants crossing illegally into the U.S. sometimes die from thirst and fatigue. He marched alongside labor union leaders, advocated for farmworkers and said prayers at AIDS awareness events.

“The support of a Catholic priest in a Roman collar was very powerful,” said Eastside AIDS activist Richard Zaldivar. “Just by his participation, he was able to open many doors for conversations around the community.”

In 1989 Estrada started a nonprofit, Jovenes, which provides counseling, job training and beds to hundreds of homeless young people each year, with a focus on Mexican and Central American immigrants.

Estrada says he relates to those fleeing violence — and to those who have experienced loss.

His father came from a landowning family in Durango, Mexico, and fled the Mexican Revolution on horseback, ending up in El Paso, where he met Estrada’s mother. The couple moved to Los Angeles, where he worked as a welder and she cleaned office buildings.

Estrada’s two older brothers were involved for a time with gangs, and both died when they were young — one of complications related to alcoholism and the other of a heroin overdose.

Johny Figueroa, 30, who ended up at Jovenes as a teenager after coming to the U.S. from Honduras, remembers Estrada as a father figure who took a stern stance on alcohol and drug use.

“He has a big heart,” said Figueroa, who decided to become a social worker after his experience with the priest. “But he’s not afraid to tell you if you’re doing something wrong.”

::

One recent night, Estrada stood before a small group gathered in the first few rows of pews at the Church of the Epiphany, an Episcopal church in Lincoln Heights. He was leading a small prayer vigil to honor several dozen college students who recently disappeared and are presumed dead in Mexico.

The audience included relatives of others who are missing. Mercedes Moreno, 66, stood and said her son had been seized by Mexican federal police in 1988 while crossing from El Salvador to the United States and was never heard from again.

Estrada, dressed in an L.A. County Federation of Labor sweatshirt, talked about Jesus — an early immigrant, he said, who fled Bethlehem for Egypt to escape persecution. And then he told his own story.

“My mom lost two kids,” he said. “After that, her life was different.

“But God is with us in our suffering,” he continued. “You are not alone.”

kate.linthicum@latimes.com

Twitter: @katelinthicum

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.