Remembering the reign of Griffith Park’s king

Sol Shankman always said that what he did was easy: Set his alarm for 5 a.m., wake up five minutes before it goes off, walk out the front door and into the hills of Los Angeles, hope for nice weather and make a few friends along the way. And maybe that was true, in the beginning. Maybe even after a few years.

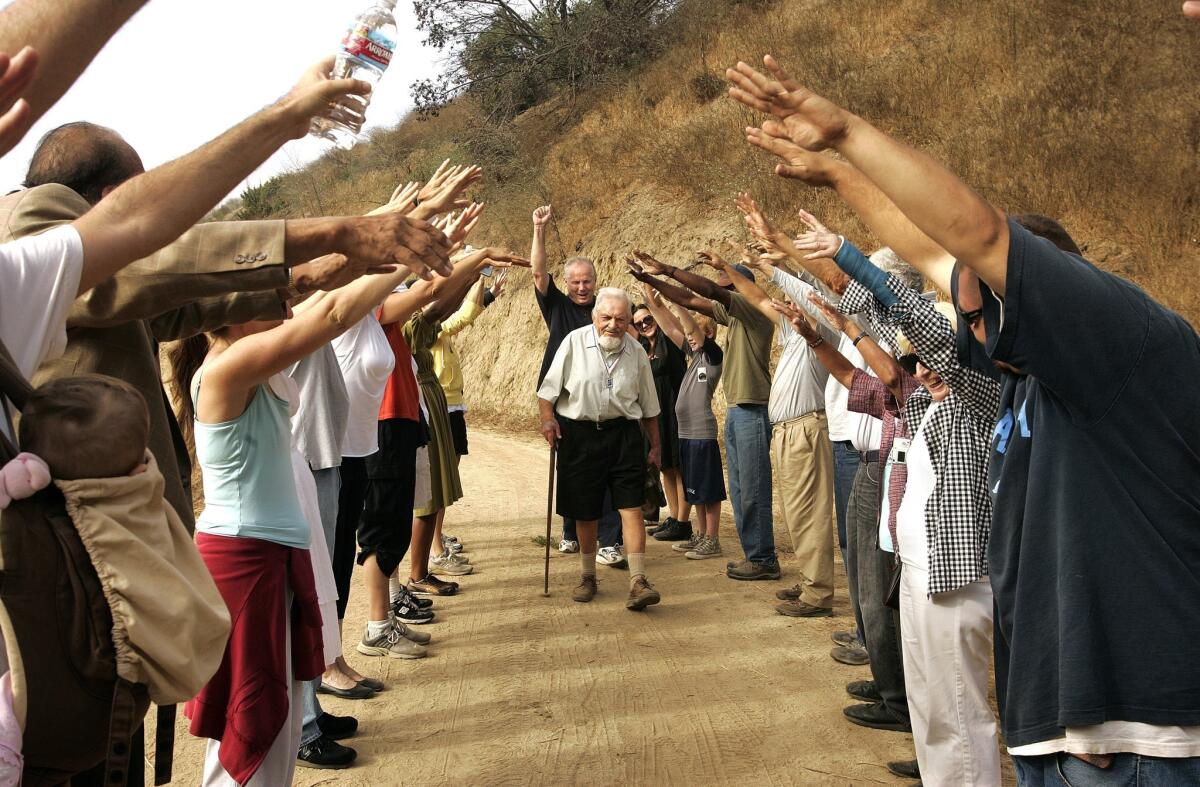

But you do that every day for 3.5 decades, and you walk the equivalent of the circumference of the Earth, all in Griffith Park, and then you make a good dent on round two, it starts to mean something. You do it rain or shine, in good health and poor, until just about everybody knows your name, well after your stride has become a shuffle, long after your eyes fail and you start asking strangers to count the birds in a tree for you, you become known as the King of the Park.

Shankman, who was celebrated on Saturday at a memorial service in the park, died last month, shortly before his 99th birthday. He was not a celebrity. He was something more — a civic institution, a status he did not seek, and sometimes shunned, but acquired anyway, one step at a time.

“The thing about a mountain is that it goes uphill. And Sol Shankman never missed a step,” said Los Angeles City Councilman Tom LaBonge, an avid park hiker and a longtime friend. “He was a beautiful man.”

Shankman suffered from Parkinson’s disease before his death, but his daughter, Janet Williamson, attributed his death to old-fashioned “old age.”

“He realized that it was time to move on to his next thing,” she said. “He’s on to his next adventure.”

Saturday was Shankman’s kind of day, warm and sunny, comfortable under the noble boughs of an oak tree. Shankman liked to call Griffith Park the city’s “lungs,” and he would have been in his glory, friends said — holding court, a cap on his head, an apple in his pocket, chewing on fresh mustard, looking ahead to the next rain, to the turn of another season.

Solomon Shankman was born in Toronto in 1915 and moved to Los Angeles in 1939. He would live in Los Feliz for the next 75 years. Armed with a doctorate in chemistry, he founded Shankman Laboratories, analyzing food and vitamin products.

He was a progressive business owner, giving his employees significant sway over the operation of the company, granting paid medical insurance and maternity leave before such things were done routinely and sometimes offering employment in the interior of Los Angeles to people who just wandered in off the street.

Around the time he arrived in California, he began courting a young cancer researcher named Elizabeth Stern. At the time, she had been dating a man who was an avid fisherman, and Shankman was not. He went to the fish market, bought a fish and asked the fishmonger to throw it to him. He then told Bess, as she was known, that he had caught a fish.

“That was the beginning of a 43-year relationship,” Williamson told the crowd on Saturday.

Shankman was never much of an athlete, and walking came late; friends suggested that he start hiking in the late 1970s when he began suffering from angina. After his wife passed away in 1980, he walked in increments from Tijuana to San Francisco. When that project was complete, he started walking up the hill from his house, into Griffith Park, and never stopped.

He is believed to have walked roughly 38,000 miles in the park, though Shankman — who could, after all, do complex math in his head and sometimes quoted actuarial tables — put the number at about 42,000.

Mike Shankman, one of his grandchildren, told the crowd Saturday that he began joining his grandfather on morning walks when he was 10. The younger Shankman remembered being woken up at the “crack of dawn,” and his grandfather “pointing out lizards and wildflowers before I was even fully awake.” Over time, he watched age set in. “His loafers would miraculously shuffle up the steep, sandy grade,” Mike Shankman said. Every time they set out, he started to wonder how long it could last.

“Little did I know that this would go on for 20 more years,” he said.

Over time, Sol Shankman became a fixture at the park, a member of a motley bunch of regulars who served as a sort of board of directors. He carried a walking stick, not to help him walk, really, but to illustrate a point during a conversation, and sometimes to write a little poem in the dirt for someone else to find. He greeted most everyone with a “howdy” and a firm handshake. His love affair with Griffith Park was real and true; he carried up water to nurture struggling matilija poppies, and he carried up seeds from a golden rain tree that grew in his backyard to sprinkle about on barren hillsides.

“Above all, Sol was a mensch,” his daughter said.

Shankman kept walking long after he was legally blind, long after his 98th birthday. He had an insatiable thirst for knowledge and conversation, and recruited people he met on the trails to come home and read to him after his eyes began to fail. Several of them could not stay away, and returned weekly for years on end. Shankman loved Edith Wharton and Melville; not so long ago, a friend finished reading him Melville’s “Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street.” It’s about a legal secretary who resists the orders of his boss with the phrase: “I would prefer not to.” Shankman loved this act of liberating defiance.

“He was always on the side of the downtrodden, the worker, the oppressed,” said Brian Strause, who read the story to Shankman.

Strause said he asked Shankman not long before his death if it had been “worth it to live this long.”

“Getting this old is the best thing I’ve ever done,” Shankman replied. “I’m like most Americans. I want more.”

“He loved life and threw himself into it,” Strause told the crowd on Saturday.

“He thirsted for new ideas. He dared to have his perceptions challenged. At an age when most people think they have it all figured out, Sol was still asking questions. He was still growing. I think this is one of the great gifts of his life. It may seem that as we age, we become set in stone. But that’s not the way it has to be.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.