Island-owning college may decide to sell

Rabbit Island, British Columbia — At the tip-top of an archipelago that stretches down to Washington state, where dozens of tiny, forested islands are traded like rare coins among the rich and impetuous, this 36-acre isle stands as a testament to infatuation.

Its newest owner, Orange Coast College, bragged — at first — about the island unexpectedly donated to the Costa Mesa community college in 2002. Small-time school snags world-class treasure! Community college gets mini-Galapagos!

Indeed, Rabbit Island’s splendor prompted gasps. Towering cedars, bald eagles and, oh, what cliffs: steep and gray and parting to the Strait of Georgia. Plus, the island had its own adventure-novel narrative: rumrunners, gold seekers and sheep rustlers once navigated nearby channels, as did men seeking refuge from slavery and the Vietnam War.

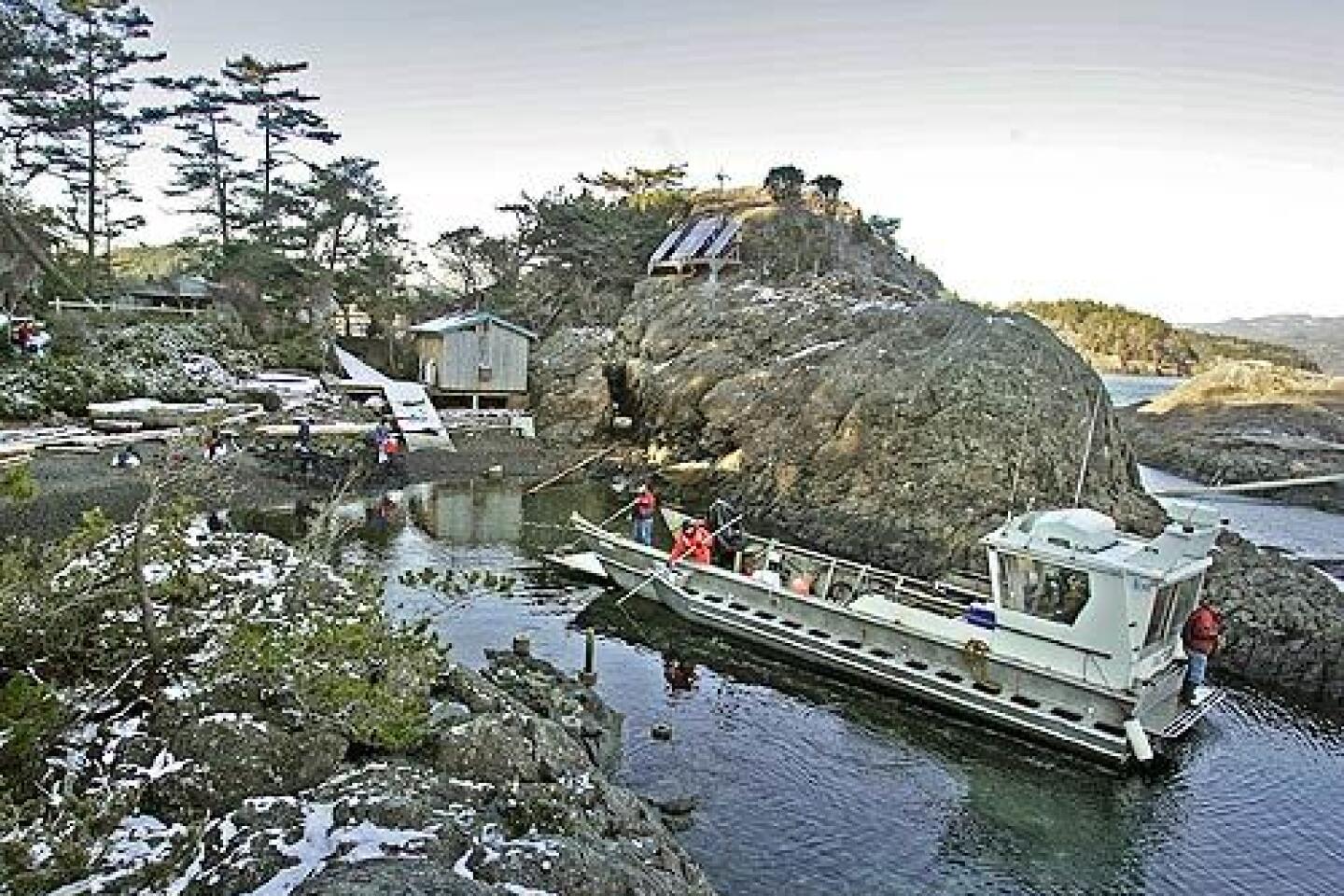

But what the college first envisioned as its own ecological diamond, a place where neophyte marine scientists could undertake first-rate research, has instead vexed officials with its harsh temperament. It’s too costly to maintain, too far north — and only 25 or so students, out of 24,000 at the school, can trek there each summer.

Now college foundation board members are pondering what would have been unthinkable just a few years ago: Should they sell their slice of paradise?

Henry Wheeler, a Long Beach sailor who runs private water companies, sometimes perused “For Sale: Island” ads in the Robb Report, a shopping guide for people with bank accounts flush enough to buy an island.

One day in 1993, decades after a sailing trip to Tahiti inspired him to own land surrounded by water, Wheeler spotted an ad for Rabbit Island at what seemed a ridiculously low price.

He flew to Vancouver, rented a small boat and cruised to Bull Passage to size up the site. The sailor was smitten.

“It wasn’t vulnerable, it was secure, there weren’t any people, there were no complications,” he wistfully recalled.

Wheeler immediately called the island’s real estate agent, who accepted his offer of $319,000 Canadian. Now Wheeler had to build his utopia on this serrated parcel, thought to be named after its resemblance to a crouching bunny.

At first, Wheeler trekked here annually and his daughter chose the island for her honeymoon. But his infatuation began to wane, along with his children’s visits to this desolate land.

“After walking the island a hundred times, you know every rock and tree and it’s not as mysterious anymore,” Wheeler said.

Wheeler also had to cope with his oddball neighbors from Lasqueti Island. Its reputation: a pot-growing hippie kibbutz.

Residents had voted down electricity and some are now battling wireless Internet in fear that radio waves could sear their brains.

His enchantment dimming, Wheeler focused on another place to escape: an upscale log cabin he had built in Missoula, Mont., near Rattlesnake Creek.

“Some guys like blonds and some guys like brunets — they’re both pretty, but no one needs to collect them both,” Wheeler said.

After almost a decade of ownership, the least Wheeler could do was play matchmaker. He had previously donated a boat to Orange Coast College, so he asked whether it wanted an island.

Gordon and Bruce Jones, de facto historians for the channel coursing past Rabbit Island, could have predicted that Wheeler and now the college would someday regret that the island didn’t come with a return policy.

The brothers, who live on Lasqueti Island, are Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary members, shellfish hatchery operators and Rabbit Island’s security team. They also restock toilet paper at a nearby island’s public restrooms — their most lucrative gig.

Rabbit Island’s history, the brothers said, didn’t deviate much from what has happened when the affluent have purchased other swaths in the Gulf Islands: Most just plain give up.

Several decades ago, the brothers said, a couple were squatting on the island until a mysterious man landed in a seaplane and told them he had bought the island. The couple skedaddled, but the brothers never again spotted the man. Their guess: He had landed on the wrong island.

The island’s next residents: a couple of men who told locals they were opening a sailing school or a retreat for burned-out corporate folks. Property records describe the dozen-year venture only as North Shore Sailing School. A few cabins were built, but nothing opened.

“Strange people buy islands,” Gordon Jones reasoned, “and things get stranger after they buy them.”

Still, the college couldn’t help falling for this rugged coast.

Some 1,300 miles south, nearly hidden amid strip malls and housing tracts, Orange Coast College has amassed an $11-million endowment and its sailing school boasts an armada of donated boats, including Roy Disney’s racing yacht, Pyewacket.

OCC officials promised to take the British Columbia property for at least two years. The ownership agreement states that if the island is sold, the college’s renowned School of Sailing & Seamanship pockets the earnings.

The college’s president later told a local paper that when he took his post, “I thought, ‘Wow, I’m not only president of a college, I’m president of a college that owns an island.’ ”

The romance between the college and the island is best described as whirlwind.

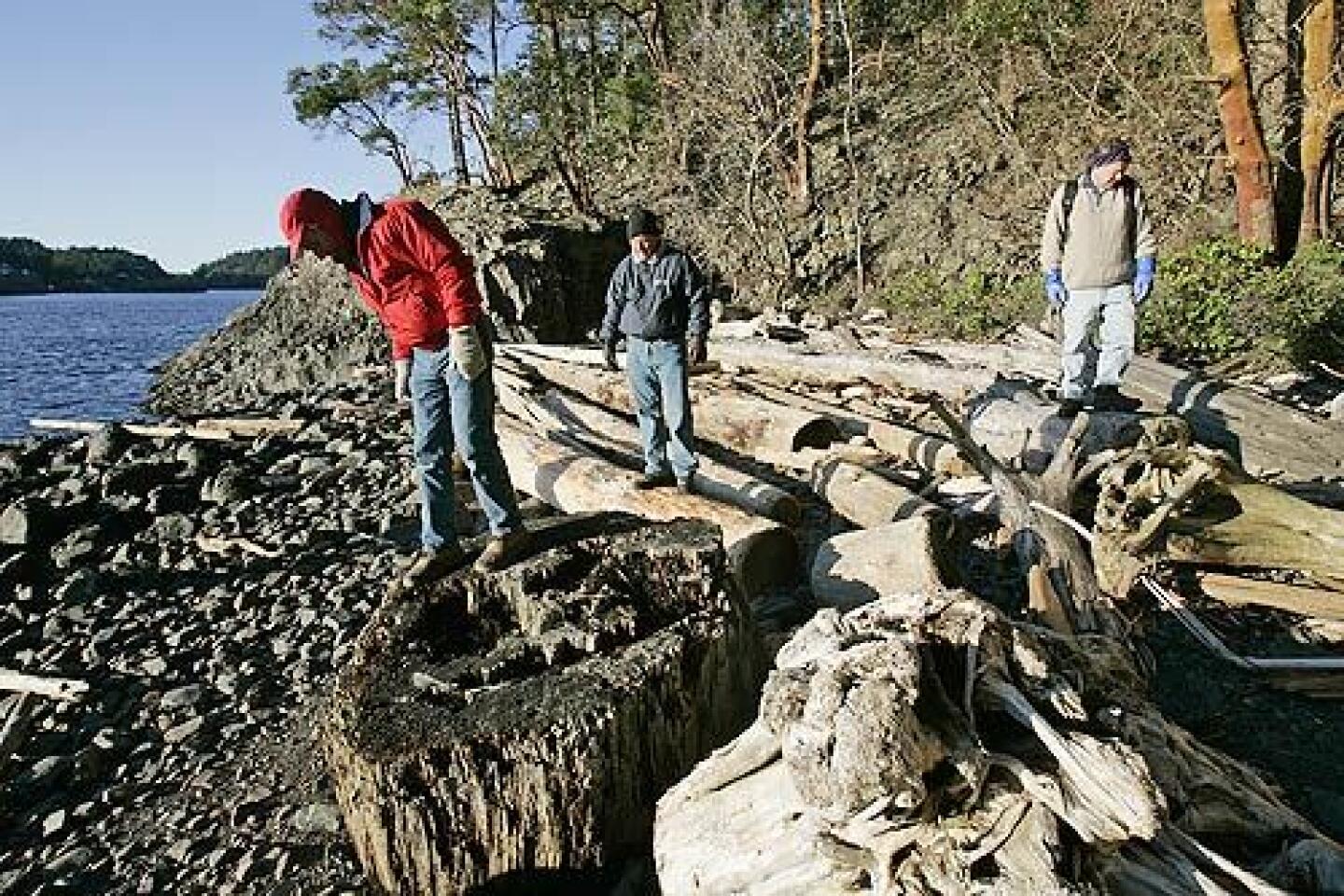

There’s little question that Rabbit Island enraptured the city-slicker students who trekked there each summer to catalog its otters, snakes, lichen, cacti and black-tailed deer. And the school was recently awarded nearly $20,000 from the National Science Foundation to figure out Rabbit Island’s best use.

Kelli Elliott, a biology instructor, was happy that Rabbit Island inspired her students to get passports, to venture outside California for the first time, to discover a place without Starbucks and traffic jams. The island is so far removed that inside the main lodge, a note above the phone gives the island’s location in coordinates — 49 degrees latitude, 124 degrees longitude — in case paramedics are needed.

“I don’t see us ever getting another island,” Elliott said.

But problems washed ashore. The island’s distance made it as hard to maintain as a relationship. Because students needed to pay for their own transportation, money ended up as a barrier between some students and the island. And it was just too expensive to tend.

The time-consuming repairs to the islands’ four cabins and solar generator, among other things, topped $200,000. The island’s annual budget has climbed to $75,000 and stretched higher as the U.S. dollar weakened.

The college foundation board now is considering whether the gift, worth $1 million, the college estimates, is an unreasonable financial drain.

But talk of selling has riled island-infatuated students. There was a tentative offer from the student government to chip in for costs. The foundation board considered other options: Local groups could rent it. Parcels could be auctioned to preservationists. A campus petition circulated: “To sell the island for quick cash boon would be a hasty and unwise use of a generous gift.”

As the college’s top fundraising official, Doug Bennett, observed one morning, pushing through the island’s snow-draped firs: “It’s complicated to own an island.”

He and the island’s caretakers were shoring up the main lodge at their recent visit’s end. Clouds hung low and dark, the kind that in children’s books foreshadow ominous things. The men damped down the fireplace and wiped down the stove’s burners. A caretaker dried a teapot painted with a rabbit.

The sole clock’s hands had halted at 5:40 — fitting, since everything here seemed stuck in limbo.

*

ashley.powers@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.