‘We found who killed your sister.’ 48 years later, a cold case is solved

It should have been an ordinary errand: a trip to a Mid-Wilshire drug store to buy a hair dryer.

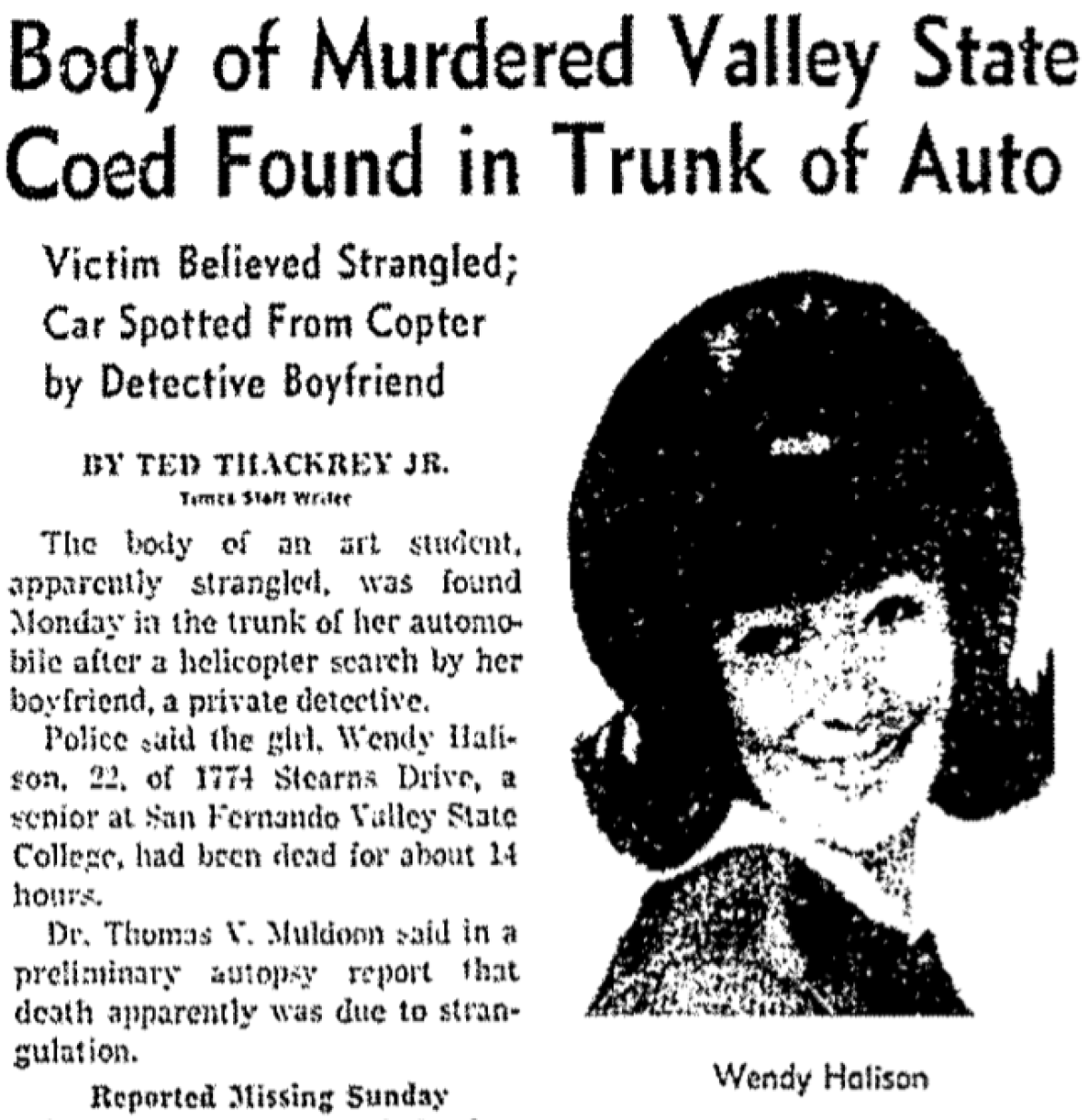

Wendy Jo Halison drove her prized green Thunderbird down Fairfax Avenue on that Sunday afternoon in 1968, stopping at the Thrifty on the corner of Wilshire Boulevard. After shopping, the 22-year-old art student was seen filling up her car at a gas station down the street.

But Halison would never return home to her family.

Her body was found the next morning, stuffed in the trunk of her car, a few blocks from where she was last seen alive.

The mystery of her murder lingered for nearly half a century, outlasting several detectives and potential suspects. New forensic techniques sometimes revealed tantalizing clues, but investigators failed to identify her killer.

Halison’s family was haunted by her death. Her parents died without learning who killed their daughter. Her sister wondered if she would too.

When an unexpected break came 48 years later, the revelations were chilling.

The man who strangled Halison had already been convicted of murdering two other women — and was suspected of killing more.

Halison grew up in Los Angeles with her parents and older sister, Linda. The daughters of a real estate salesman and a bookkeeper-turned-homemaker, the girls painted and played the piano. Halison was gregarious, with a big smile that still beams through the black-and-white photos hanging on her sister’s wall.

She took classes at San Fernando Valley State College — known as Cal State Northridge today — and lived in a Mid-City home with her parents and her beloved poodle, Pierre.

“She had everything going for her,” recalled Gil Kort, who was then married to Halison’s sister.

Halison called her sister that Sunday about a newspaper ad for a hair dryer on sale at Thrifty and asked if she wanted to go buy one.

Linda Kort Trocino told her sister no — she had two young sons at home and wanted to spend the day with her family. Decades later, her eyes welled with tears as she recalled the conversation.

“That still haunts me,” she said.

When Halison didn’t return home later that day, her family began to worry. It was unusual for her not to check in.

Halison’s mother called police that night to report her missing, but was told they couldn’t launch a missing persons case so quickly. Rather than wait, the family began to search on their own.

Gil Kort was a private investigator and rallied friends to help. He also hired a helicopter to scour the neighborhood from above.

Less than an hour after the search began the next morning, Halison’s boyfriend spotted her Thunderbird parked on Fairfax Avenue. Kort found her keys on the floor of the back seat and went to open the trunk.

Halison’s body was inside.

“It was the worst day of my life,” Kort, now 77, recalled.

Investigators later determined Halison was sexually assaulted, then strangled, said Richard Bengtson, an LAPD detective now handling her case. Her fingernails were broken — detectives think she tried to fight her attacker.

The rope used to kill her was found at the scene. She still wore her jewelry and watch, causing detectives to rule out robbery as the motive. The only thing missing was the hair dryer.

Trocino was waiting at her parents’ house when her husband walked in. It was the first time Trocino had seen him cry, she recalled.

“We found her,” Kort told them. “She’s gone.”

Police quickly zeroed in on four men who knew Halison well: her boyfriend, an ex-boyfriend, her brother-in-law and another friend. They guessed that she might have known her attacker, someone who knew she was shopping alone.

The boyfriends, however, especially stood out to investigators, Bengtson said. The one who had spotted Halison’s car from the helicopter had seemingly picked a needle out of a haystack. Even the pilot wondered how he was able to see the car from where they were flying.

He also failed a lie detector test, raising more eyebrows.

Kort said he took a polygraph test right away, so police could eliminate him as a suspect and move on with their search. He said he understood why detectives initially focused on the men close to Halison.

“I thought it was somebody that knew her,” he said. “Strangling somebody is very personal.”

But the weeks turned into months and the months into years without much progress. Detectives were able to glean some clues — a white man was seen near Halison at the drug store and again at the gas station — but the case ultimately stalled.

Harry Klann Jr., a criminalist for the LAPD, got involved three decades later when storied detective Frank Bolan asked him to look at evidence collected in Halison’s case.

In 1998, DNA analysis was in its infancy and the LAPD had been working with the forensic technique for only about four years, Klann said.

But when a colleague found semen on Halison’s capri pants and underwear, Klann said, they decided to analyze it in hopes that DNA would yield a fresh lead. Sure enough, he said, they found a sample from the suspect.

I thought it was somebody that knew her.

— Gil Kort, Wendy Jo Halison's brother-in-law

Investigators went to work, drawing blood from each of the four men they had originally questioned in connection with Halison’s death. They eliminated all four as suspects.

“Now you can move on,” Bengtson said. “It closes one door, but opens up others to look at.”

But the investigation stalled yet again. The DNA samples were too meager to test against collections in state and national databases.

“It just wasn’t going anywhere,” Klann said.

He recalled talking to Bolan about the case late one night as the detective smoked a cigarette outside Tom Bergin’s, a bar just down the street from where Halison’s body was found.

“This case will be solved long after I’m gone,” Bolan told Klann.

Halison’s death — and not knowing who was responsible — devastated her family.

Her parents left her room intact. For years, Kort avoided driving down Fairfax, and felt sick when he saw Thunderbirds on the road.

Halison’s father, Lee, diligently stopped by their neighborhood police station, asking if there were any new leads. He offered rewards looking for anyone who might have seen Halison that day.

The family thought of the milestones Halison was robbed of: a wedding, birthdays, watching her nephews grow up, having children of her own.

Halison’s death seemed to hit her father the hardest. She was born on his birthday, and her absence hung over every celebration.

“If something happens to me, I want you to promise, don’t forget your sister,” he once told Trocino. “And you do what you think you can do to find out who did this.”

By 2016, three LAPD investigators had been working Halison’s case for years: Klann, the criminalist; Bengtson, the cold-case detective; and Peter Berman, a former head deputy district attorney who now helps detectives look over old cases for new clues.

Bengtson was assigned to the department’s Robbery-Homicide Division, a group of detectives who handle some of the toughest cases in the city. He was among the original eight detectives assigned to the cold case unit when it was created in 2001, and the only one of those still working there.

Bengtson is of the classic detective mold, with a deep voice, sharp eye for detail and a determination to find answers. He doesn’t like the word “closure,” he said, because he’s not sure families of those killed will truly gain it.

At his desk inside the division, thick binders line the cubicle behind him. Halison’s files — what detectives call the “murder book” — are neatly arranged on his desk.

The investigators frequently flipped through those files, looking for the clues that could lead them to Halison’s killer.

Last summer, they asked Klann to run the DNA again, hoping improved technology would finally help them identify enough markers to upload the sample in the state’s system.

When Klann got the results, he said, he immediately sent Bengtson a text message.

“Are you sitting down?” he wrote.

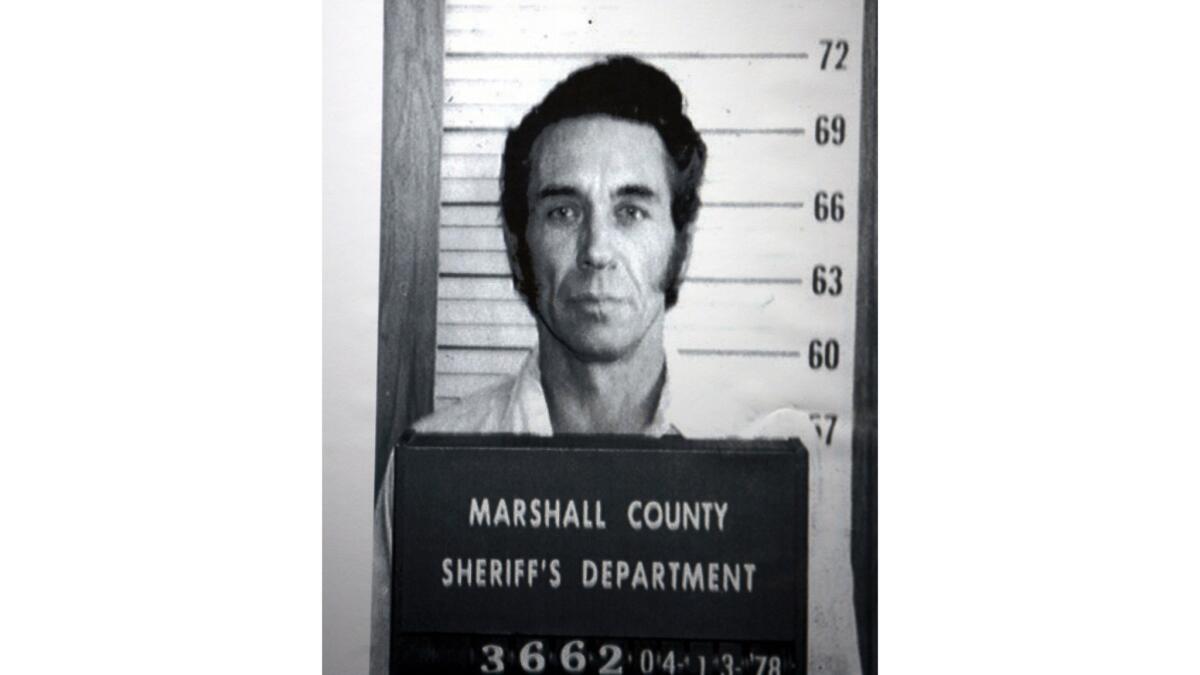

Edwin Dean Richardson’s criminal record stretched to his childhood, escalating from burglaries and thefts to more violent crimes scattered across the country. He was a drifter, working odd jobs as he moved from state to state.

In 1960, he was convicted of attempted robbery and kidnapping in San Diego and spent eight years behind bars. He was paroled in April 1968 — five months before Halison was killed.

Richardson landed in an Ohio prison in 1981, after being convicted of killing 21-year-old Jo Anna Boughner in Belmont County, a steel-and-coal community on the state’s eastern border. Richardson was also convicted of kidnapping two girls across the river in West Virginia.

Tom McCort, now 76, was Belmont County’s sheriff for two decades. Before that, when he was an investigator for the prosecutor’s office, he spent more than three years looking for Richardson, who skipped town after Boughner’s body was found.

McCort eventually used a phone bill tossed in the trash to track Richardson to a trailer park in Mesa, Ariz., where he was arrested for Boughner’s murder. On the flight back to Ohio, the retired lawman said, Richardson bragged about killing another woman, wrapping her body in a blanket and tossing it over a cliff.

“He was almost boasting about what he had done and what he had gotten away with,” McCort recalled.

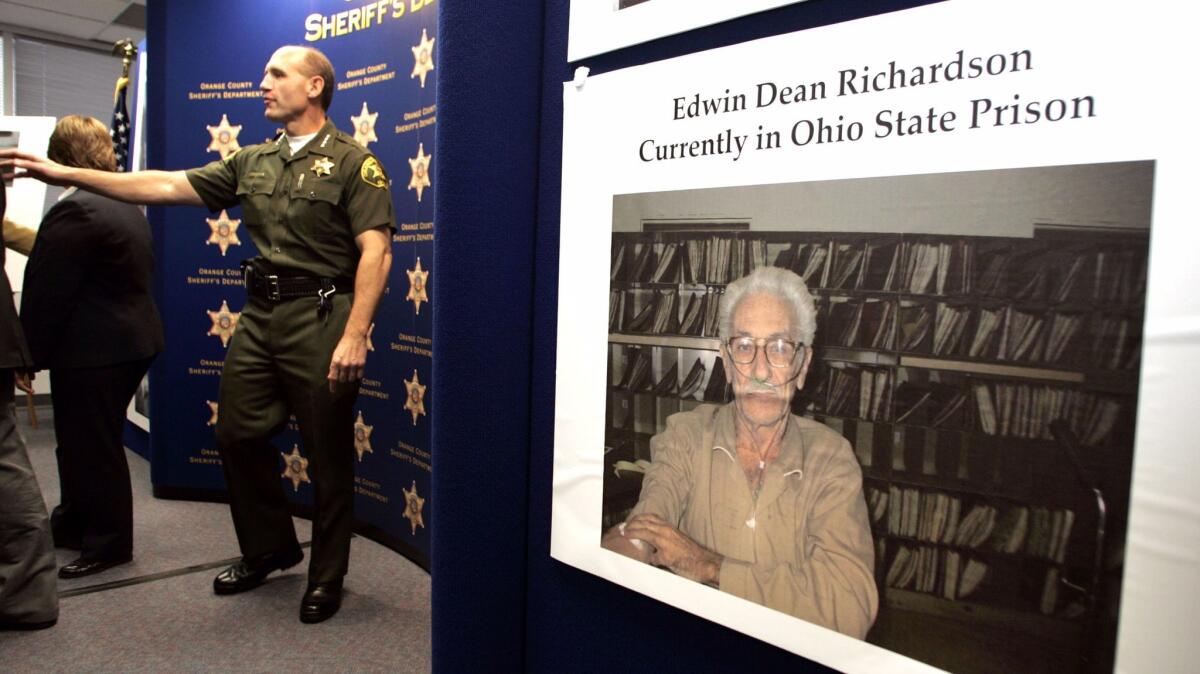

About 20 years later, authorities used DNA to link the still-imprisoned Richardson to a cold-case killing in Orange County.

Richardson was flown to California to face trial, where he pleaded guilty to raping and strangling Marla Jean Hires in 1972. The 23-year-old’s battered body was wrapped in cloth and dumped down an embankment not far from the Yorba Linda Country Club — just as he told McCort on the plane.

Richardson, then 70 and suffering from emphysema, was sentenced in 2006 to life in prison, all but ensuring he would die behind bars.

“He was a little sniveling coward,” McCort said. “The only people that I could think of that I had to deal with that were of a more sickening nature were pedophiles.”

“To me, he fit right in the same category — preying on the weak and defenseless,” he added.

By the time the investigators in L.A. used the DNA to identify Richardson as the man who strangled Wendy Jo Halison, the convicted killer had been dead about four years.

Bengtson cursed at the news.

“Even alive and in prison is better than dead,” the detective lamented. “Because then I get to go to him and say: ‘Guess what? I’m going to put another charge on you.’”

Because Richardson was dead, investigators couldn’t interview him in prison or, more importantly, take a sample of his DNA to confirm their initial hit. Instead, they matched a blood sample identified as Richardson’s in the Orange County investigation to the DNA from Halison’s case. They also combed through his background, to see if his habits matched those of Halison’s killer.

As they did, Bengtson said, they noticed disturbing similarities.

Halison, Hires and Boughner were all young, attractive brunettes who were alone when they were abducted. Each was assaulted and strangled. Their cars were abandoned.

Bengtson thinks Richardson was an opportunist, targeting women who were about to get in their cars. The detective believes he used some type of weapon to force them to slide into the passenger’s seat.

There are gaps on his rap sheet that worry Bengtson and the others. A killer like Richardson — a serial killer — doesn’t typically take a break, they said.

“This guy didn’t stop at one or two or three,” Bengtson said. “There’s no chance in hell.”

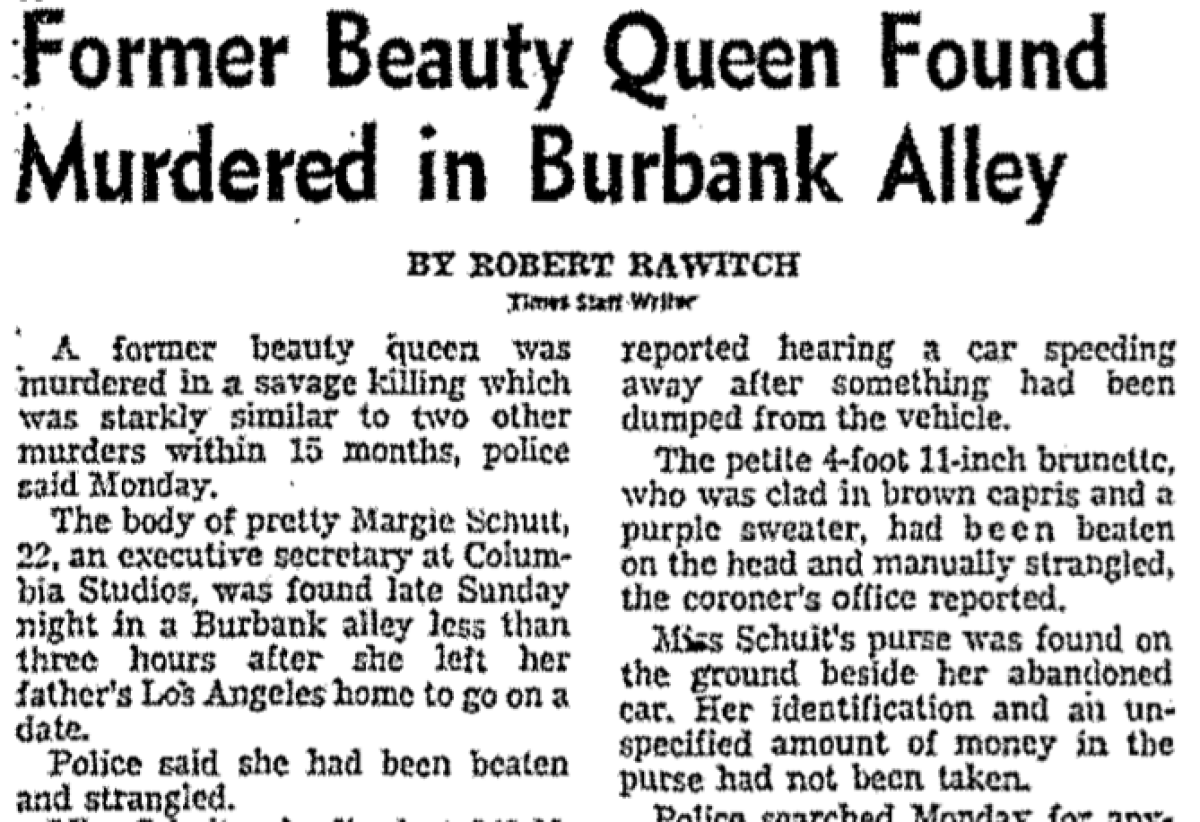

There was another woman, another pretty 22-year-old killed a year after Halison. Margie Schuit’s beaten and strangled body was found in Burbank, but her car was found in Los Angeles — in the parking lot of the same Thrifty drug store where Halison shopped.

It’s too much of a coincidence for Bengtson and Berman. They think there’s a chance Richardson killed Schuit too.

The problem, they said: The evidence from Schuit’s 1969 killing was lost. There is no DNA to test.

When Bengtson was confident Richardson was the man who killed Halison, he picked up the phone to call her sister. Those calls are “a little nerve-wracking,” the detective admitted, because he knows they bring a wave of mixed emotions to the victim’s relatives.

“All at once, it’s just a hurricane hitting them,” he said.

Trocino was eating brunch with her husband when she got the call.

She didn’t answer at first, assuming it was a telemarketer, and let the call go to voicemail. When she listened to the message, she said, she immediately felt sick.

“We found who killed your sister,” Bengtson said.

Earlier this month, Trocino and her husband, Tony, drove to the LAPD’s glass headquarters in downtown L.A. to meet the investigators for the first time. A necklace that once belonged to her sister hung around her neck.

Trocino sat quietly, her hands folded and her eyes wide, as the investigators patiently answered her questions. At 48 years, it was the oldest cold case they had solved, they told her.

When Bengtson walked through Richardson’s criminal history, Trocino shook her head.

“You OK?” her husband asked, rubbing her back.

“Unbelievable,” she said.

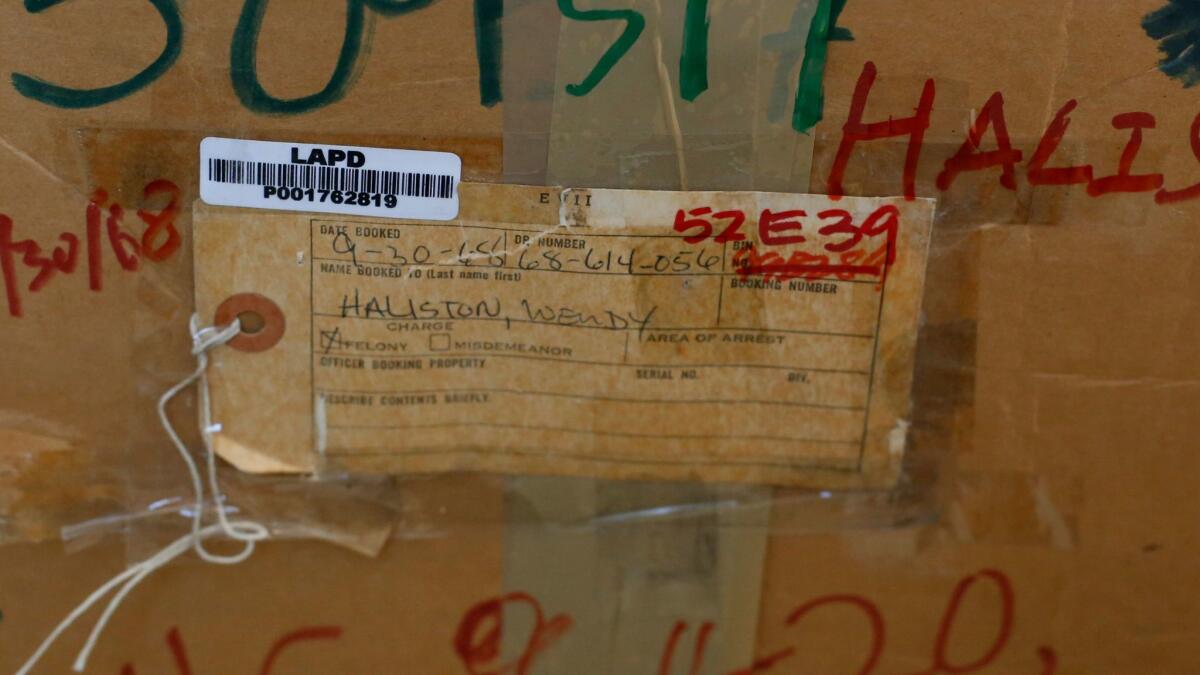

Bengtson turned to two cardboard boxes that held items police found in Halison’s car: school papers, some letters, her driver’s license. One box still had the original evidence tag detectives filled out in 1968; the paper used then to wrap her belongings was disintegrating inside.

“I wish there was some way I could thank you,” Trocino said. “It just means so much.”

When the hourlong meeting ended, the investigators helped carry the boxes to the couple’s SUV, where they chatted a few minutes more.

“The LAPD did its job and the case is closed,” Trocino’s husband told the detective. “But the case will never really be closed, because we’ll never forget Wendy.”

Twitter: @katemather

ALSO

'Money fell from the sky': At the doughnut shop across from the Americana, the mall workers rest and dream big

Jailed woman says she livestreamed aftermath of deadly crash to raise funds for sister's funeral

Naked, filthy and strapped to a chair for 46 hours: a mentally ill inmate's last days

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.