Serial rapist’s search for housing underscores challenges of release

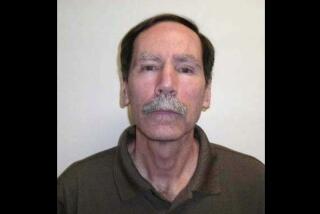

Ending a 13-month ordeal to reintroduce him to society, a man who admitted sexually assaulting more than 40 women over about 12 years is scheduled to move this month into a small, white house in the blustery desert east of Palmdale.

On a dirt road near Palmdale Boulevard, the isolated 800-square-foot house is surrounded by more snake holes than trees and there is barely a footprint in the soft sand.

Serial rapist Christopher Hubbart’s move there from a mental health hospital in Coalinga came after Santa Clara County Judge Gilbert Brown found in May that the so-called pillowcase rapist no longer posed a risk of committing more offenses and could be released with a GPS bracelet to his county of last residence.

Despite protests from neighbors and politicians fighting to keep him away, Hubbart, 63, is set to become the 28th sexually violent predator to be released under similar circumstances. State-sponsored housing searches for the offenders have been arduous because of restrictions on where they can live. But the decade-old, uproar-filled process has remained the same.

Limited housing options have pushed predators into crime-infested motels, trailers next to prisons, RVs and, in one case, a tent beside a river.

These situations, the predators and their advocates say, are more dangerous for people and more expensive than keeping the offenders in housing close to the health services they need.

Mental health officials said supportive neighbors rather than ones vilifying him would better serve Hubbart, who was prosecuted before the state passed the three-strikes law.

“There’s not much out there for destitute people, let alone destitute people convicted of crimes that society despises them for,” said Laurie Mont, a Contra Costa County public defender.

The housing searches have lasted an average of about 10 months, ranging from half a month in sparsely populated Tehama County to nearly three years in densely packed San Francisco, according to interviews, court records and media reports. One judge who was frustrated by the long process threatened to hold in contempt the state contractor searching for housing, saying that he would demand that the state either buy the sexually violent predator a house or release him as homeless.

“The whole thing is ‘Alice in Wonderland’ upside down,” Santa Barbara County Dist. Atty. Joyce Dudley said. “These are the people that need the most amount of stability and support. You have to release them to where they can succeed.”

Since 1996, California civil court judges have been able to order that violent sexual offenders with mental disorders indefinitely move to a mental hospital after leaving prison. Last year, about 40 people were institutionalized, five successfully petitioned to get out and another handful died while institutionalized.

All told, courts have released 200 offenders from hospital care. Most had to find housing on their own, and 79 of them remained in California as of the beginning of 2014, according to an analysis of the state’s sexual offender registry. But courts have let 28 of the offenders, including Hubbart, leave through an outpatient treatment program in which the state covers the housing search and rent.

Under a state contract, worth up to $2.1 million in 2014, Liberty Healthcare Corp. does what a regular house hunter would do — scan Craigslist, talk to real estate agents and drive through neighborhoods in search of “For Rent” signs. But most inquiries go unanswered, or landlords hang up when they hear that they might receive death threats.

John Posthuma, who offered a Palmdale home for Hubbart last year, was among those who backed out. He said he ends relationships “when I find I’m dealing with someone not upfront and honest.”

Another landlord offered his Lake Los Angeles property, and despite public outcry, Brown ordered Hubbart moved there in May. The owner, Martyn Haggett, did not respond to requests for comment.

Community members are considering opening a child-care center down the street to trigger restrictions that bar sex offenders from living closer than a quarter-mile from schools and parks. Sharon Duvernay said that having Hubbart become her closest neighbor makes her “sick,” and she said she hopes such a plan works.

“When the opportunity arises, someone who is a serial rapist is going to take it,” she said.

The restrictions and community resistance produce a difficult search, state officials said. Public defenders and other critics of the sexually violent predator program say that the state has let the program’s cost rise — $200,012 a year for those on conditional release — without evaluating its effectiveness or improving the search.

“If there is no housing found, he can’t stay locked up forever,” Hubbart’s public defender, Jeff Dunn, said earlier this year.

In 2004, it took two lawyers meeting at a softball game to secure permanent housing for Cary Verse after Liberty struck out for more than a year. Verse, who was convicted of sexually victimizing three boys and a man, first bounced between motels as protesters pilloried him from one neighborhood to the next. At the game, a defense attorney offered a cottage behind his office.

Worried that the plan would be scuttled like the others, Verse said recently, he took it with “a grain of salt.” It worked out though, and among other jobs, he now drives a streetsweeper.

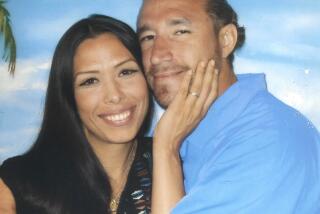

Verse said he has talked to Hubbart, who was nicknamed the pillowcase rapist because he shrouded victims’ heads with a pillowcase before raping them.

“When you have a situation like that where you have your own label, it’s a tough sell,” Verse said ahead of Hubbart’s release. “I’ve told him, ‘Hang in there. Stay as optimistic as you can,’ because he knows it’s going to happen eventually.”

Anthony Ashe said he and his wife reconsidered accepting Verse. They went forward after asking themselves, “If not us, then who would provide this service?”

“A pain to do,” Ashe said, “but one of the better things I’ve done.”

Of the offenders conditionally released before Hubbart, Verse and eight others are free from supervision. Six are in a mental hospital or prison for violating program rules.

No one has victimized anyone while on conditional release, said Kristin Spieler, a San Diego County assistant district attorney. She and other prosecutors credited that to GPS monitoring and daily visits by Liberty officials.

But Spieler said the hundreds of people who protest each release might feel safer if the program could have a continuous location in each county.

“We need to find a more global way of handling these, so there isn’t community upheaval every time one of these cases comes,” she said.

Times data analyst Ryan Menezes contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.