This was hardly a fair fight

At 6:30 in the morning Tuesday, Debora Lutz of the U.S. Forest Service got the first sign she was in for a hellacious day in the air war against the Witch.

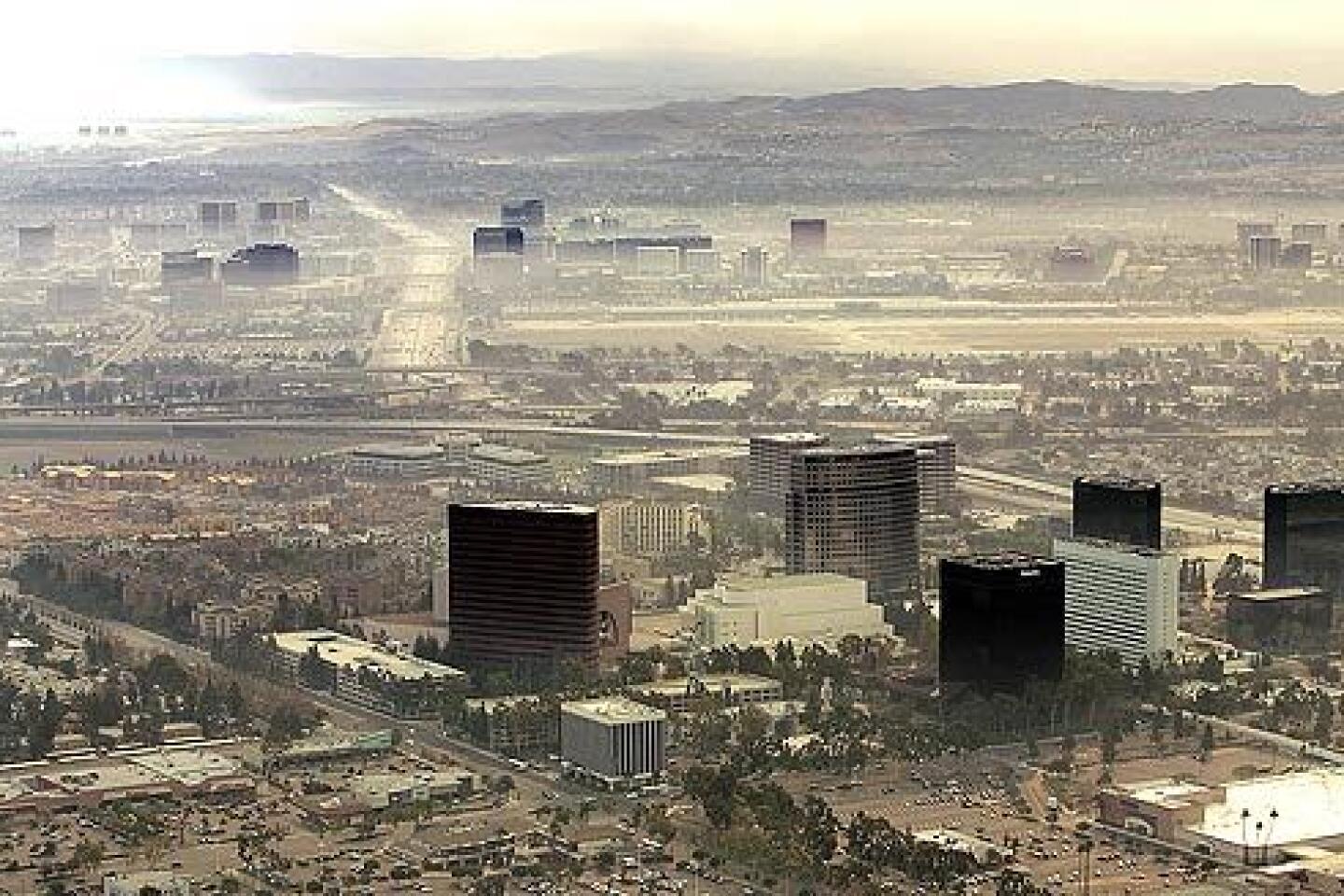

The Witch fire in northern San Diego County had already devoured more than 150,000 acres, and was eating its way down the San Dieguito River Valley, heading straight for the blue-chip seaside real estate of Del Mar and Rancho Santa Fe.

And now -- good morning, Battalion Chief Lutz -- the city of Ramona’s main water pump had died, courtesy of a burning power transmission line.

That could mean no water to fill the bellies of Lutz’s small, ad hoc fleet of air tankers based at Ramona Airport. No water to dilute the blood-red fire retardant to the proper color and consistency of strawberry milk.

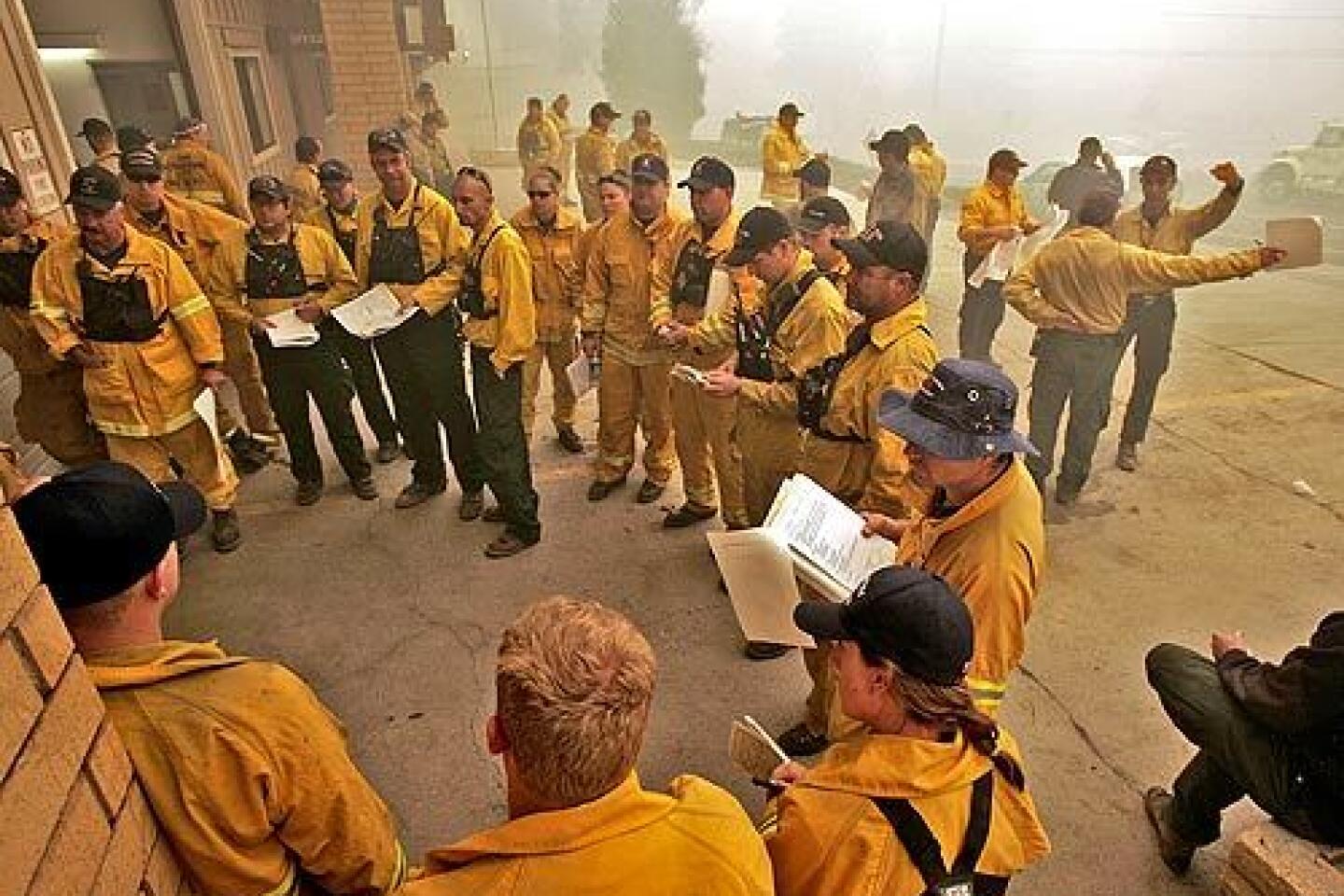

The four tankers, along with three spotter planes, comprised the entire fixed-wing air force deployed against not only the monstrous Witch fire, but also the Harris fire blazing to the southeast of San Diego, and the Rice fire , about 60 miles north. Lutz had been begging her superiors for more planes, dreaming especially of a DC-10 that could carry about 12,000 gallons of liquid, ten times the load of one of her tankers.

It was in operation elsewhere, she was told.

“We’ve told them to give us everything they have,” she said. “None are available.”

In the hushed second-story control room, Lutz, who is 50 and wears her blond hair in a long ponytail, held soft-spoken sway, banishing loud talkers so she and her CalFire colleague Shari Lee could attend to the constant crackle of radio traffic from the planes.

A sign on a nearby wall read, “Don’t let these innocent smiles fool you. They are cruel, vicious women.”

Through two large windows they looked out on a broad expanse of ranch homes, horse stalls and palm trees encircled by distant mountains, many of them ablaze.

On the pavement outside, great spills of undiluted fire retardant stained the ground red. Every few minutes, planes landed and refilled, returning from short flights. The smell of smoke blended with that of aircraft fuel. The air was filled with the shouts of refueling and refilling crews straining to be heard above the din of propellers and engines.

With the main city water pump disabled, crews brought on line an electric pump of their own to keep the water flowing. Airport power interruptions kept stalling the pump throughout the morning, and workers had to switch to a gasoline-powered generator to keep it running.

Meanwhile, water pressure throughout Ramona began to drop. The pressure drop, which started at higher elevations, was working its way down to the basin and the airport.

The previous night, a small blaze dubbed the Poomacha fire had broken out near Mount Palomar, and by 8 a.m. had grown to consume 1,000 acres. Just before 12:30 p.m., Pat Kershen, of the state Department of Forestry and Fire Protection and overall commander for the Witch fire, received an e-mail informing him that Poomacha had become a 22,000-acre conflagration and was working its way up Mount Palomar itself.

“We’re approaching biblical proportions,” said Kershen. “I’m waiting for Pestilence next, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.”

Poomacha meant an additional theater of operations for the strapped Ramona fleet.

A little after noon, Battalion Chief Ray Chaney, a spotter in one of the planes, came into the control room to grab a cheeseburger and take a half-hour break. “The whole county is on fire,” he announced.

Chaney’s crew had been busy dousing Mount Woodson, which became a sudden priority. A fire was racing up the mountain toward major communications towers for the San Diego County Sheriff, the California Highway Patrol, the FBI, and numerous other law enforcement and emergency agencies.

That left no planes immediately available for Mount Palomar.

“The perimeter of the fire is huge,” Chaney said. “You’re looking at an entire pillar of fire from the Mexican border to the Palomars. There are literally a hundred places you could target. But you can only do so much at a time.”

Over the radio came the voice of an airborne pilot flying near the Witch fire . “It looks like an atom bomb is going off over there,” it crackled.

John Richardson, the CalFire official in charge of all air operations for the Witch fire -- including fixed-wing aircraft heading to blazes from Hemet and a helicopter base at Gillespie Field in El Cajon -- arrived at the Ramona airport in time for a 1 p.m. conference call with other air operations commanders in Southern California.

For 45 minutes, the participants bemoaned the difficulty of getting additional aircraft and crews. Bad enough that the aircraft in use were pushing half a century in age. Not even designed for fighting fires, some had bullet holes from the Vietnam War.

“When you need a priority aircraft, you can’t get anyone,” said Richardson. “I hate going outside the chain of command, but it might be 20 minutes before you can get anyone on the phone.”

At about that time, another crisis emerged. The Ramona Airport itself -- at least a section at the end of the runway -- was ablaze. And there were no firefighting crews around to put it out.

Airport officials called for help, and waited. The airport manager wanted to shut the place down.

Firefighters arrived just in time, however, and flight operations were not interrupted.

Finally, at 2 p.m., a spotter plane and crew from Paso Robles arrived, a harbinger of other out-of-area aircraft headed for San Diego County to augment Ramona’s fleet.

But at 2:30, before it could be deployed against the Witch fire , the Paso Robles plane was diverted to a new fire that had broken out on the Camp Pendleton Marine base.

By 3 p.m., the airport’s water problems had coalesced into a full-blown crisis.

City water pressure had dropped so low the airport pumps couldn’t coax any water from the system. Worse, tanker trucks sent to the water district’s main pumping site were turned away.

Only a 90-minute supply of water to dilute the fire retardant remained on hand.

Lutz and half a dozen tanker truck drivers stood racking their brains for a solution.

One trucker suggested they drain the Ramona High School swimming pool; there was not a great deal of water for firefighting purposes there, but what existed might help.

Another trucker said he knew of someone with a well.

So as Lutz dispatched some truckers to the high school, Richardson got on the phone, trying to get permission to procure water from private wells.

The good news at 4:15 was that five additional planes, including a DC-10, had arrived from out of the area.

The bad news 20 minutes later was that water for diluting retardant had run out.

Ramona’s air war was over.

The planes were sent to Hemet, to operate from there today.

“We’re still rolling along with no end in sight,” Battation Commander Perry Hall, a spotter based at Hemet, said late Tuesday. “With Ramona closed, we’re about to become very busy.”

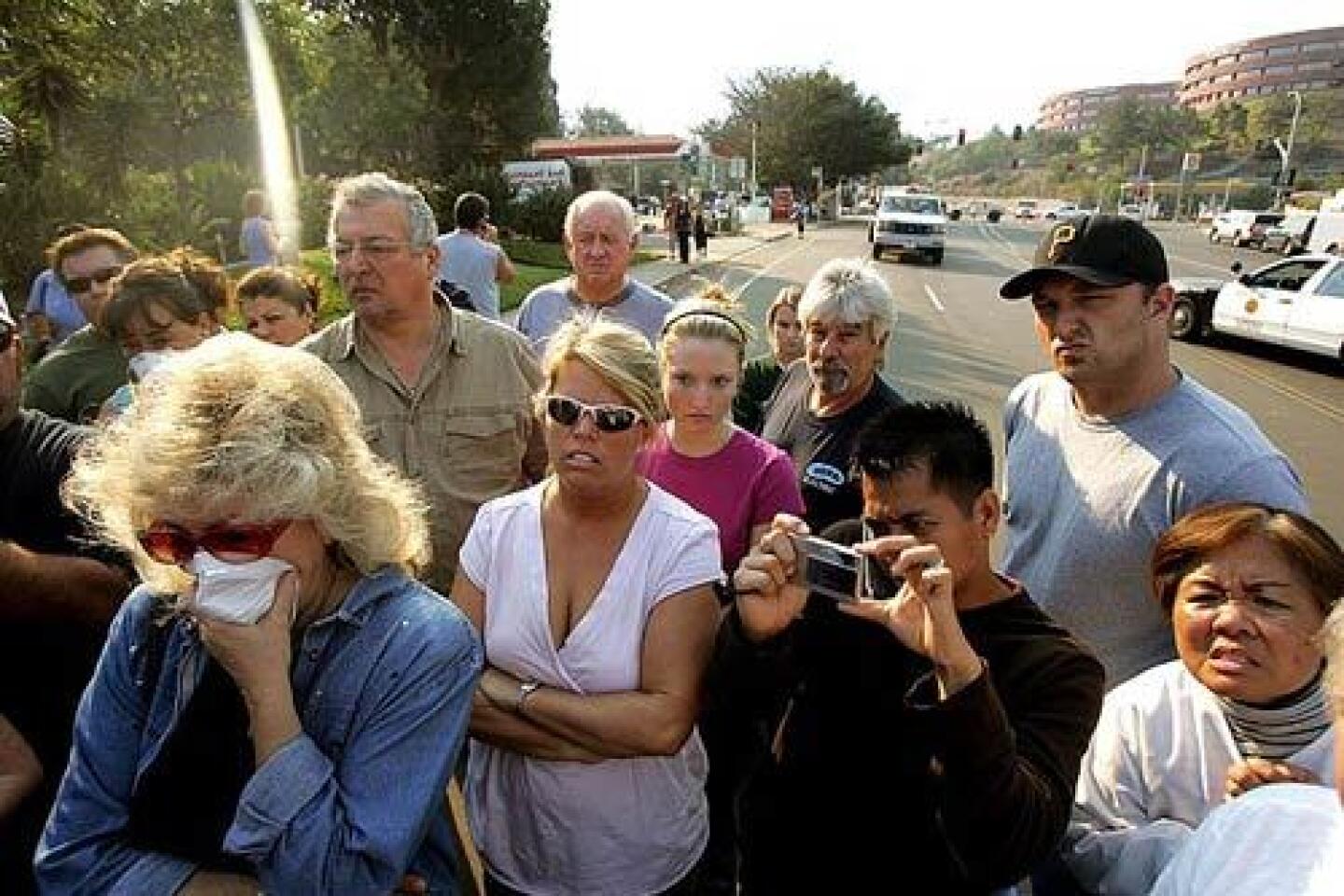

Tuesday evening, the Witch fire had hesitated on its march to the sea, nibbling at the original settlement of Rancho Santa Fe but not crossing the 5 Freeway. Numerous homes were still under attack in neighboring communities to the east, and firefighters concentrated on the ones they deemed saveable.

Overall, winds had subsided. At Mount Woodson, officials scrambled to get ground crews on the mountain before the wind could pick up speed. The strategy was to break the fire up and limit the damage to communications towers at the top of the mountain if the blaze resumed its upward trek.

At Ramona Airport, with operations ended, Debora Lutz began the long task of assessing costs.

Her day had started at 5:30 a.m. and looked to be courting a midnight finish.

She said that although her calm demeanor might have belied it, adrenaline had been rushing through her all day.

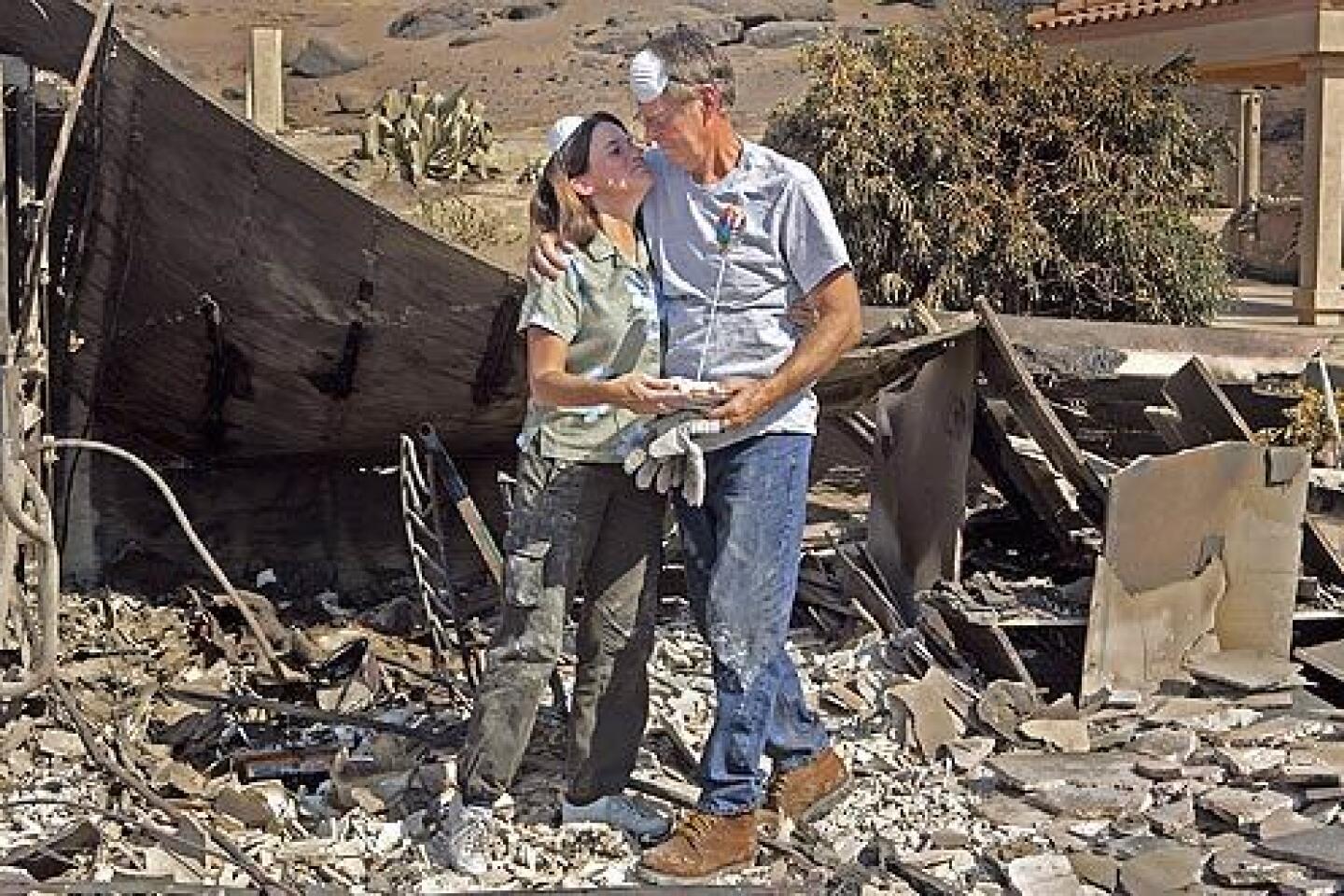

Lutz was not entirely a stranger to what hundreds of owners of burned houses in her area of operations were enduring. She’d lost part of her home to the Cedar fire of 2003.

“One guy here loading the tankers with retardant lost his home. He was here working that day and he came back to work the next day,” she said. A tear leaked through a small crack in her composure. “We try to save everyone’s home, and we just can’t do it. We don’t have the resources.”

Times staff writer Richard Marosi contributed to this story.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.