Monstrous tunnel-boring machine makes history at the lowest point in L.A.’s transit system

BREAK THROUGH! The tunnel boring machine sees daylight in Downtown L.A. (Video by Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Below Walt Disney Concert Hall, down the block from the line forming outside the Broad Museum, sits the deepest point in Los Angeles’ subway system.

When it’s completed, the Bunker Hill station will be in a class of its own. At 110 feet below street level, it will be the only station without escalators, instead relying on a bank of elevators to lower passengers to the platform.

For the record:

12:14 p.m. April 26, 2024An earlier version of this article said the new Regional Connector Transit Project would save riders from “money-sucking” transfers. Transfers are free systemwide for the first two hours of travel.

On Thursday, the site became a part of L.A. transit history.

In front of a gaggle of TV cameras and eager spectators, the crews made way for Angeli, the monstrous tunnel-boring machine that has been devouring bedrock beneath downtown Los Angeles since February, as it worked its magic.

At 110 feet below Grand Avenue at 2nd Street, downtown’s chorus of car horns and roaring vehicles is nothing more than a distant gray noise. Instead, the sounds of boots on metal platforms, power generators and a crane winch’s high-pitched squeal create the ambiance. Rows of sealed utility and power lines curve over the top of the cavern like an industrial art installation.

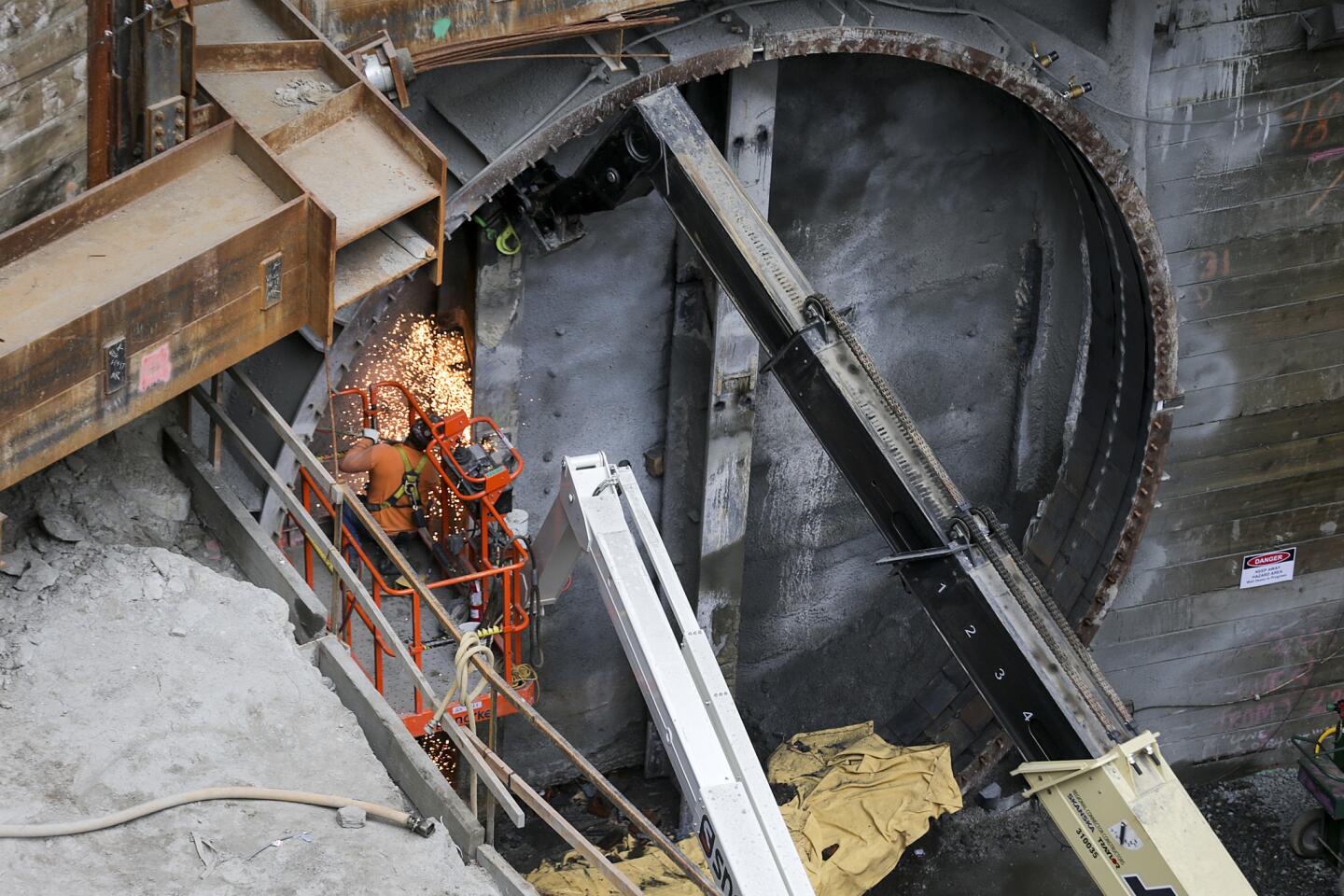

When Angeli approached its final destination for the day on Thursday — the end of a 22-foot-wide tube previously sealed by concrete — a deep thunder akin to cracking ice sheets boomed through the job site.

“It sounds like King Kong behind the gates,” one worker joked.

And minutes later, when the machine’s wide face of scrapers, discs and cutters gnawed through the wall, officials celebrated the event as a milestone in the construction of Metro’s Regional Connector Transit Project.

Chunks of rock, mud and dirt spilled onto the ground while the machine’s mud-caked face continued to twist while swallowing dirt and spitting water to loosen the soil.

“I’m a big proponent of public transportation, most of our guys are. We’re proud to be a part of this,” said project engineer Christophe Bragard.

The 1,000-ton, 400-foot-long machine began its subterranean journey four months ago in Little Tokyo. After breaking through a wall of earth at the planned Grand Avenue Arts/Bunker Hill Station on Thursday morning, the machine will veer left and continue digging through downtown’s Financial District until it reaches 4th and Flower streets in a couple of weeks.

When the entire $1.75-billion project is completed in 2021, the S-shaped tunnel will allow commuters to use a single train to move from Long Beach to Azusa and from East L.A. to Santa Monica, linking some of the county’s most far-flung residents without time-consuming transfers.

“The dream of connecting the Metro Rail system to the entire region is now becoming a reality,” Metro board chair John Fasana said in a statement.

Angeli journeyed 1,440 feet from Little Tokyo to Bunker Hill, said Metro spokesman Rick Jager.

Crews have already set 18,000 tons of precast concrete in the machine’s wake and sealed the tube with 1,000 gallons of grout.

After Angeli reaches 4th and Flower streets, it will be returned to Little Tokyo, where it will begin digging a second, parallel tunnel. Each tunnel will take about six months to complete, according to Metro.

The light rail tunnels ultimately will connect Metro’s Blue, Expo and Gold Lines. The tunnels also will connect three new stations from Little Tokyo to the Financial District: 1st/Central Station in Little Tokyo; 2nd/Broadway Station near the Civic Center; and 2nd Place/Hope Street Station near Bunker Hill.

The line is expected to serve 88,000 riders daily, including 17,000 new passengers, and cut travel times for some up to 20 minutes.

Los Angeles was once considered an unlikely place for such grand ambitions, the soil deemed too gassy and unpredictable.

A methane explosion in a water tunnel in Sylmar in 1971 killed 17 miners. In 1985, underground gas accumulated in a clothing store at 3rd and Fairfax streets, and when it blew up, nearly two dozen people were injured, leaving many to question the wisdom of building a regional subway system.

Gas wasn’t the only problem for the city’s first underground. In 1994, as Red Line crews burrowed beneath Hollywood, its star-studded boulevard sank 10 inches, and two years later, the 101 Freeway dropped nearly 4 inches.

Not long after, a new style of tunneling machine came on the scene as the Metropolitan Transit Authority built the Gold Line.

By keeping steady pressure on the earth while excavating, operators minimized subsidence and heaving — sinking and bulging — the twin evils of tunneling. And with the miners enclosed in a capsule the diameter of the tunnel, dangerous gases could more easily be vented.

With the old equipment, the ground might move as much as an inch and a half, the project’s chief mechanical engineer, Richard McLane, told The Times. On this project, he said, sensors have picked up movement of no more than 0.16 inch.

For breaking California news, follow @JosephSerna on Twitter.

Staff writer Thomas Curwen contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.