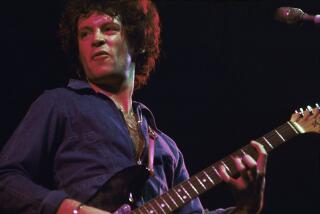

Charlie Louvin dies at 83; country singer

Charlie Louvin, the country singer whose scintillating harmonizing with his brother Ira created a distinctive template for duet singing that strongly influenced the Everly Brothers, the Beatles, the Byrds and successive generations of singers including Gram Parsons, Emmylou Harris, Beck and Jack White, died Wednesday in Nashville of complications from pancreatic cancer. He was 83.

The Louvin Brothers’ sound, with Ira’s pure high tenor typically floating atop Charlie’s strong tenor-baritone melodies but often switching mid-song, derived from church-based “shape-note” singing, an a cappella style they picked up while growing up in their musically inclined family in rural Alabama.

They became arguably the most influential harmony team in the history of country music, and thus made their impact on countless country and bluegrass singers as well as a broad spectrum of rock and pop acts. They were a key influence on the Everly Brothers, the country act that made the biggest pop crossover of all the sibling country groups. By extension, they helped shaped the sound of the Beatles, who were huge fans of the Everlys.

“They influenced everybody by the quality of their music,” Phil Everly said Wednesday through his son, Jason. “Harmony just got a lot better in heaven.”

In addition to their signature harmonizing, the Louvins wrote numerous songs that have become classics in country and bluegrass music, among them “If I Could Only Win Your Love,” which gave Harris her first Top 10 country hit; “When I Stop Dreaming”; “Every Time You Leave”; “The Christian Life,” covered in the ‘60s by the Byrds and more recently by the Raconteurs; and “The Great Atomic Power,” which Jeff Tweedy’s alt-country band Uncle Tupelo recorded in the 1990s.

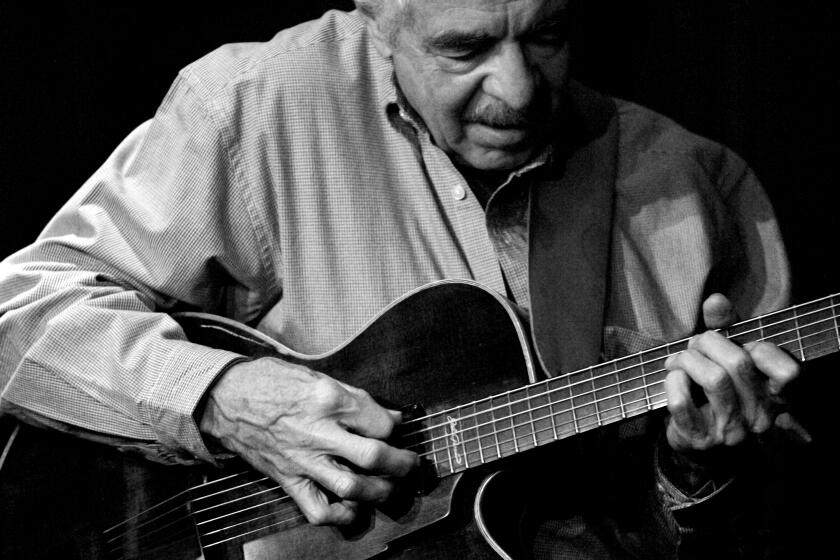

“Whether you’re just a fan or a working artist who was influenced by them, I think we owe them a huge debt — both of them,” Chris Hillman, a founding member of the Byrds and the Flying Burrito Brothers, told The Times on Wednesday. “Charlie did not just fade away into the woodwork after Ira died, even though he was the dominant member of the group. Charlie had hits of his own, and had a great career, and he was vital all the way up until he got this pancreatic cancer. He had plans to do another album, and we wanted to do [the Burrito Brothers’ song] ‘Sin City’ together.”

Said Harris: “He really changed the world of music, Charlie did. I know that, for me, hearing the Louvin Brothers brought me that fierce love of harmony.”

In a statement, Dolly Parton called him “one of my truly good friends, someone I loved like a brother. The Louvin Brothers were my favorite when I was young and growing up in the business.”

Added Garth Brooks, through a spokeswoman: “Charlie Louvin was [one] of the pioneers that not only led the way in traditional music and entertainment, but was influential in lending a hand to the next generation coming up with the dream of continuing the tradition of the [Grand Ole] Opry and what it represents. Truly, a good man.”

Charlie Eizer Loudermilk was born July 7, 1927, one of seven children who grew up on the family’s 23-acre farm in Sand Mountain, Ala.

His brother Lonnie Ira, who was three years older, got a mandolin when he was 19 and urged his 16-year-old brother to learn guitar so they could play music together. Their father played a banjo but believed that music should be properly used for recreation, not as a career.

But after the Louvin boys earned $3 each for playing music all day at a Fourth of July celebration in Flat Rock, Ala. — more than six times the 50 cents their father was paid for laboring from dawn till dusk on the farm — Ira and Charlie started viewing music as an escape route. They changed their name for the stage, and later legally, because “we got tired of being called ‘Ira and Charlie Buttermilk’ or ‘Ira and Charlie Sourmilk,’” Charlie said later.

The brothers played whatever shows they could, performing on radio when the opportunity arose, and, after each brother’s brief military service, started making records in the late 1940s for a succession of labels, without great success.

After being dropped by MGM Records, Hank Williams’ label, they landed a contract with Capitol Records, singing gospel music.

“They didn’t need us as a country duet,” Charlie recalled later, “but they would hire us as gospel duet. They had Jim and Jess [McReynolds] and, in the old days, a label wouldn’t have more than one country duet. We said, ‘OK, we’ll take that. Anything.’”

But their gospel records didn’t connect in a big way either. In 1955, they decided to try their luck with a secular song they’d written, “When I Stop Dreaming.”

It became their first top 10 hit, thanks to their harmonies that used unconventional intervals drawn from the shape-note tradition and poetically bittersweet lyrics of a broken love affair.

You can teach the flowers to bloom in the snow

You may take a pebble and teach it to grow

You can teach all the raindrops to return to the clouds

But you can’t teach my heart to forget

That was followed quickly by their only No. 1 single, “I Don’t Believe You’ve Met My Baby.”

“What’s so impressive to me,” said John Rumble, senior historian at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville, “is that they broke through with a style that was essentially a throwback to the 1930s brother duet style in an era in which honky-tonk and country pop were the sound of the day, and their biggest hits came in 1955 and ‘56, just as rock ‘n’ roll was exploding. That was no mean feat.”

Ira’s erratic, alcohol-fueled behavior made him an increasingly unpredictable quantity that rattled nervous concert promoters, and the Louvins’ bookings began tailing off in the early ‘60s. It also affected the brothers’ creative partnership.

“I gave ideas and helped on lines,” Charlie once said. “He definitely was the stronger part of the writing team. But he was a drinking man. He’d get to drinking and write something and just bring the words over and say ‘Get your guitar. I want to try this song.’ I was supposed to know what tune he had in mind just looking at the words. A lot of times the tune was made up as we went. But if I screwed up, he’d wad it up and throw it in the trash can, saying it probably wasn’t worth a damn anyway.”

Charlie decided to go it alone and proceeded to score hits through the late ‘60s and into the ‘70s. Barely two years after the brothers parted ways professionally, Ira was killed in 1965 while on his way home from a solo show in Kansas City, Mo., when his car was struck by a drunk driver.

Years later, although Charlie never sounded as though he regretted his decision, he did believe that had Ira lived, “We would’ve gotten back together, I’m sure,” he told the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 2007. “But it wasn’t meant to be. I didn’t know if I could make it as a solo artist, but music was the only thing I knew. So I gave it a try. Thanks goodness, it worked.”

Louvin continued appearing regularly at the Grand Ole Opry, which had inducted the Louvins in 1955, and in 2003 began a career renaissance that led to accolades from younger audiences and bookings at major outdoor festivals including Stagecoach in Indio and Bonnaroo in Tennessee.

A 2003 multi-artist tribute album, “Livin’, Lovin’, Losin’ — The Music of the Louvin Brothers,” featuring new versions of their songs by Parton, Merle Haggard, Vince Gill, Rodney Crowell, Marty Stuart and others, won the Grammy Award for best country album in 2004.

“A lot of people probably don’t realize that he and Ira probably were the reason there was an Everly Brothers, an Emmy and Gram, and all the other great family acts,” Gill said Wednesday. “It was all so Louvin-inspired.”

In 2003 Louvin signed with the Tompkins Square label and subsequently released five albums, most of which drew critical praise and earned two Grammy nominations.

Marty Stuart, who first met Louvin when Stuart was a teenage member of bluegrass musician Lester Flatt’s band, said, “Growing up in the South, the Louvin Brothers were part of the atmosphere, like the scent of magnolias, they were part of the breeze .... I once heard a statement about Hank Williams: His songs could sometimes go where he couldn’t. That’s pretty profound, and I think the Louvins’ songs were that way too. They went beyond anything they could dream of as kids coming off of Sand Mountain, Alabama. They’re country music royalty, no doubt.”

Of his late-career renaissance, Louvin noted, “Mostly I’m singing to grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the people Ira and I played to 60 years ago. It’s a real thrill to be able to stay around that long.”

Lucinda Williams, who invited Louvin to tour with her in recent years, said Wednesday that “Losing Charlie means that we have lost one of the last of the founding fathers of honest-to-god country music.”

“Charlie was eternally youthful, full of spitfire, vim and vigor and, like Hank Williams, was a true punk, in the best sense of the word. We will miss Charlie, but like he said shortly before he left us, ‘I’m ready to go home.’”

Robert Hilburn, The Times’ former pop music critic, said Wednesday, “Charlie Louvin’s voice echoed the heart and defining spirit of country music for more than a half century. Every time he stepped on a stage or into a recording studio, he inspired other singers to reach for those same qualities in their own work. He never gained a mass following, but he couldn’t have been more respected within the musical family of country music itself.”

Louvin is survived by his wife of 61 years, Betty; three sons, five grandchildren and three sisters.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.