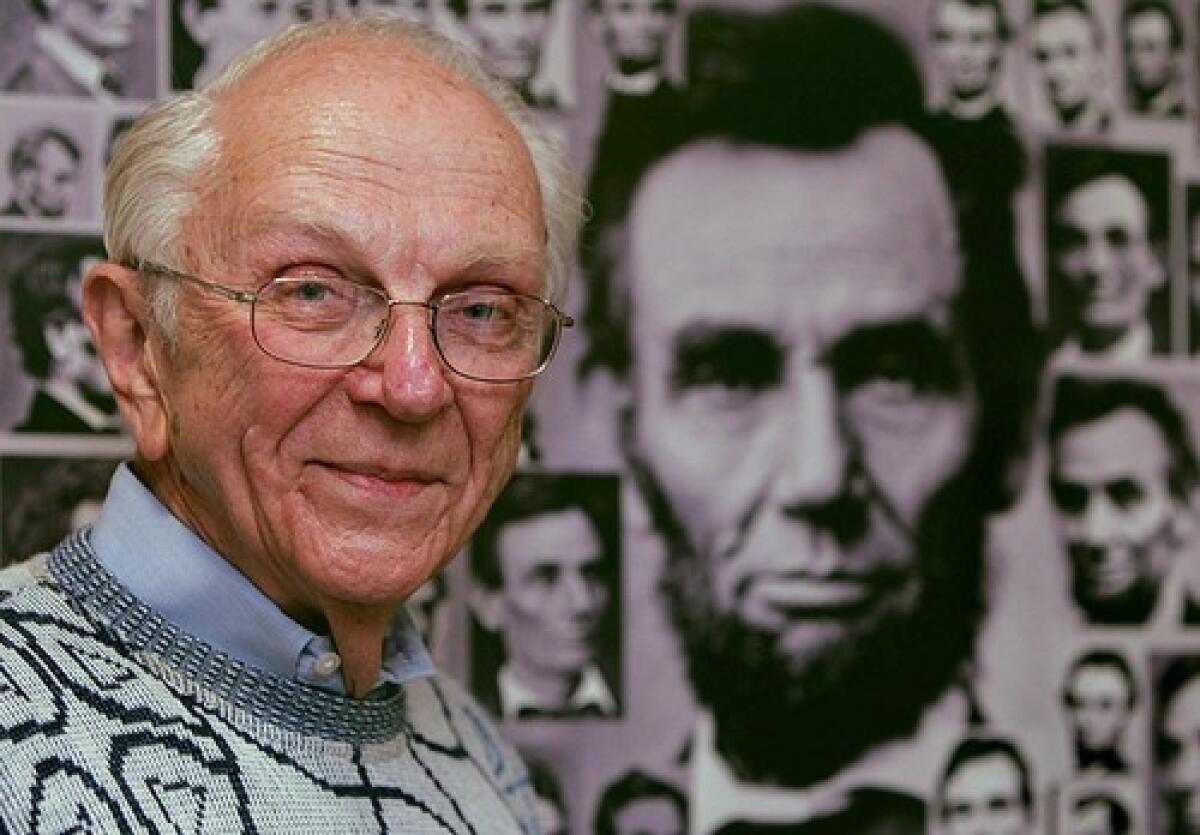

David Herbert Donald dies at 88

David Herbert Donald, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian of the Civil War and American South whose expertise on Abraham Lincoln brought him a wide general audience and reverence from his peers, has died. He was 88.

Donald died of heart failure at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston on Sunday while awaiting heart surgery, said his wife, Aida.

A professor emeritus at Harvard University, Donald won Pulitzers for biographies of abolitionist Charles Sumner and novelist Thomas Wolfe. But his books on Lincoln became his legacy. Presidents from Kennedy to George H.W. Bush summoned him for lectures, and fellow scholars acknowledged his prominence, especially as Lincoln’s bicentennial was celebrated this year.

“He was not only one of the best historians of our era, but he was also one of the classiest and most generous scholars I have ever met,” said Doris Kearns Goodwin, author of “Team of Rivals,” a best-selling Lincoln biography.

Donald’s stature was so high among Lincoln experts that an award was named for him, the David Herbert Donald Prize for “excellence in Lincoln studies” given by the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Museum in Springfield, Ill. In 2005, Donald was the first honoree.

Before his death, he had been working on a “character study” of John Quincy Adams, his wife said.

Donald published his first Lincoln book in the late 1940s and kept at it for more than 50 years. His books included “Lincoln,” a single-volume biography of the president published in 1995; “Lincoln at Home,” a study of his family life; and “We Are Lincoln Men,” essays about Lincoln’s friends and associates.

Donald, the grandson of a Union cavalry officer, was born into a farming family in Goodman, Miss., in 1920. He majored in history and sociology at Millsaps College in Jackson, Miss., then went to the University of Illinois for graduate school.

Having grown up in a segregated town, he was interested in race relations and planned to study the post-Civil War era. But he also needed money and found a job working as a research assistant to a leading Lincoln scholar, James Garfield Randall.

Donald’s mentor encouraged him to write about Lincoln’s law partner, William Herndon. “Lincoln’s Herndon” began as a dissertation and became Donald’s first book, published in 1948.

Donald’s reputation grew throughout the next few decades as he carefully picked apart the Lincoln myths dear to poets, dreamers and politicians. In such classic essays as “Getting Right With Lincoln” and “The Folklore Lincoln,” he noted Lincoln’s transformation from laughingstock to saint upon his assassination and the efforts of both Democrats and Republicans to claim him for their parties.

During a 2005 interview with the Associated Press, Donald acknowledged that his feelings about Lincoln, too, had changed.

“When I started out, I wasn’t interested in Lincoln, and frankly found him a tiresome old fellow who was rather long-winded, told too many stories, was kind of a rough, frontier sort,” said Donald, who dismissed more recent theories that Lincoln was gay or chronically depressed.

“As I grew older, I realized the jokes and stories he told were really very funny and they always had a point to them. And I watched the way he worked with people and what an extraordinarily adept politician he was. . . . He was much more sensitive and human than I had thought before.”

Donald married Aida DiPace in 1955 and had one child, Bruce Randall. The Donalds moved to Lincoln, Mass., in the 1970s, not in homage to the president, but because of good schools and proximity to Boston.

In addition to his wife of 54 years and their son, Donald is survived by two grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.