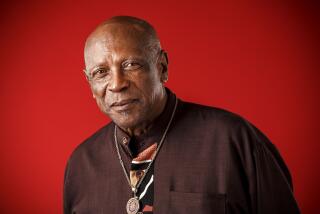

Dickie Moore dies at 89; leading child actor of movies’ golden age

Child actor Dickie Moore, who was in “Our Gang” comedies and numerous notable films, was so used to the limelight by the time he was 6 that when he got a birthday card for his mother, he signed it, “Your friend, Dickie Moore.”

But like many child actors, his transition to adulthood was difficult.

“People don’t want to see you as you are now, but as you were then,” he said in a 1984 Associated Press interview, “because that’s what they remember, and enjoyed, and made money off of.”

Moore, 89, who eventually became successful apart from acting and had a long marriage with actress Jane Powell, died Sept. 7 in a Connecticut hospital.

He had been suffering from dementia and died of natural causes, said Helaine Feldman, president of Dick Moore & Associates, a New York public relations firm he founded.

Born John Richard Moore Jr. on Sept 12, 1925, in Los Angeles, he was known for his big brown eyes, mop of dark hair and cherubic face. Even as a baby, his looks got him a job — a casting director spotted him at 11 months and wanted him for a scene in the film “The Beloved Rogue” starring John Barrymore.

At first, Moore’s mother resisted having her baby in the movies, but with his father out of work, the income was needed.

Moore quickly became a steadily working actor. By the time he was in the “Our Gang” short “Hook and Ladder” (1932), he had appeared in more than 30 features and shorts.

From the start, he was a standout in the kiddie comedy shorts. “He became a most endearing leading man,” according to the book “The Little Rascals: The Life and Times of Our Gang” by Leonard Maltin and Richard Bann.

Moore’s success made it even more difficult for his father to find work because employers assumed the family was swimming in money. Moore was the de facto breadwinner, which was not unusual for child actors of the era.

“All of us shared common lives, huge responsibilities and salaries that shriveled fathers’ egos,” he wrote in his 1984 book about child actors, “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star (and Don’t Have Sex or Take the Car.)”

Even while appearing in the shorts, Moore was getting feature exposure, most prominently in Josef von Sternberg’s “Blonde Venus” (1932) in which he played the son of Marlene Dietrich, and “So Big!” (1932) starring Barbara Stanwyck, one of his favorites to work with.

“Affectionate and demonstrative, she was easy to understand,” he wrote in his book. “She was a direct and gracious woman, who seemed extremely interested in whatever interested me.”

After only about a year of being in the “Our Gang” comedies, he left for more work in features, starring in a 1933 production of “Oliver Twist.” Among his other credits: “The Story of Louis Pasteur” (1936) with Paul Muni; “The Bride Wore Red” (1937) with Joan Crawford; the highly regarded film noir “Out of the Past” (1947) with Robert Mitchum and Kirk Douglas (he played the small but key part of a boy who was deaf and couldn’t speak); and his favorite film, “Sergeant York” (1941) with Gary Cooper.

Moore caused a sensation in the 1942 “Miss Annie Rooney,” when he gave Shirley Temple her first on-screen romantic kiss. (She was 13 when the film debuted, he was 16). Even though it was just a peck on the cheek, it made headlines.

Prolific as he was, Moore found the work to be nearly torturous.

“Every time I got in front of the cameras, I felt like it was an X-ray machine,” he said in the AP interview, “like I was ashamed of or embarrassed about what was revealed to everyone who was watching me.” As he grew out of his teenage years, his popularity ebbed.

Moore served in the Army during World War II, writing for the Stars and Stripes newspaper from the Pacific theater. After the war, he used the G.I. Bill to study journalism at Los Angeles City College.

“I had learned how to do something,” he told the Washington Post in 1984. “I could edit a magazine, work on a newspaper.” The child stars who had particularly difficult times adjusting to adulthood “were never encouraged to do anything else.”

Moore’s last feature film was “The Member of the Wedding” (1952).

His path to a non-celebrity life was not entirely smooth. He spoke in interviews of substance abuse, a suicide attempt and failed relationships.

But moving to New York, he appeared in some plays and became involved in actors’ unions, eventually opening his agency to represent them. Moore became known as a show-business insider, so much so that he had a regular, prominent booth at Sardi’s.

He found that writing his book, for which he interviewed numerous former child stars, was cathartic. One of his most memorable reunions was with the biggest child star of them all, Shirley Temple.

“I was afraid she’d barely remember me,” he told AP. “But when she opened the door, the first thing she did was point to her cheek and say, ‘Kiss me there, like last time.’ ”

In addition to his wife, Moore is survived by his son Kevin Moore and sister Pat Kingsley.

david.colker@latimes.com

Twitter @davidcolker

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.