Hotshots’ final radio call: ‘Our escape route has been cut off’

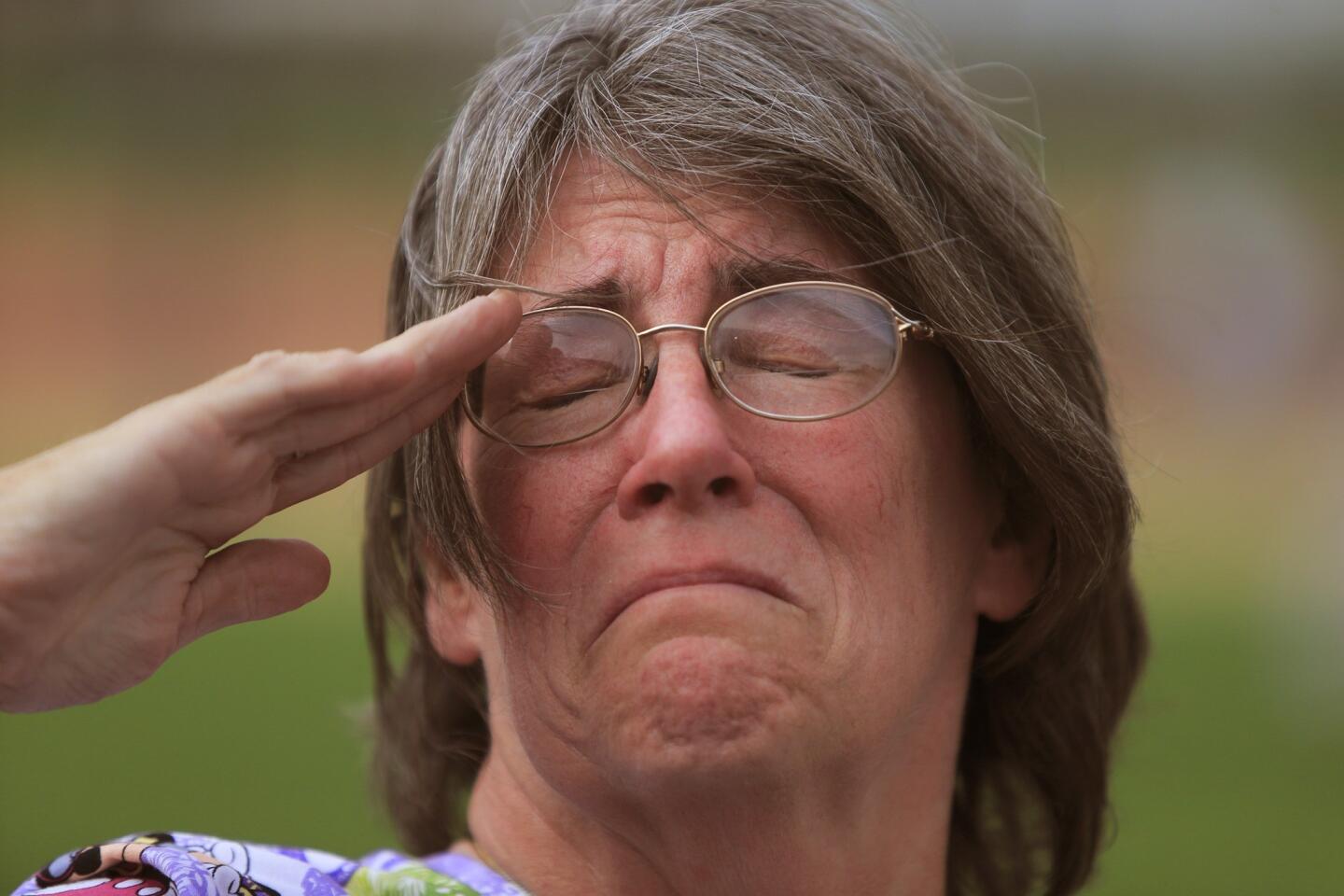

The final radio call from the Granite Mountain Interagency Hotshots came in at 4:39 p.m. as a wall of fire was racing toward Yarnell, Ariz.

That call, described in a report released Saturday about the tragedy that claimed 19 lives, provides further details on the crew’s last moments in the deadly June 30 fire. Until that call, it had appeared the crew was headed for safety.

Then officials heard the voice of Eric Marsh, the crew’s superintendent.

“Yeah, I’m here with Granite Mountain Hotshots. Our escape route has been cut off,” said Marsh, sounding increasingly frantic as he shouted for air support. “We are preparing a deployment site and we are burning out around ourselves in the brush and I’ll give you a call when we are under the sh — the shelters.”

But Marsh never called back.

The course the disaster took is well known: A shift of wind fed the flames’ growth, suddenly changed the blaze’s angry direction and left the men no path to escape.

But the 116-page report commissioned by the state of Arizona – conducted by local, state and federal fire officials, along with independent experts – included new details about the horrors of the conflagration that nearly swallowed Yarnell and became the deadliest wildland fire in the U.S. since 1933.

A torrent of fire moving 10 to 12 mph – faster than a human running a six-minute mile – overran the firefighters from Prescott, Ariz., covering the final 100 yards in 19 seconds. The flames had simply moved too fast for all the men to take cover. Temperatures reached more than 2,000 degrees.

Rescuers found tools with handles simply burned away.

The stark report was most immediately notable for its refusal to assign blame to anyone for the worst firefighter tragedy since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Officials said that all official policies appeared to have been correctly followed, that the Granite Mountain crew was appropriately rested and trained, and that negligence or recklessness did not seem to have occurred.

It also detailed what is known of the crew’s last movements. Instead of choosing other routes that were safer because they’d already been burned, the report states, the Granite Mountain team appeared to take a path back to Yarnell that would have allowed them to rejoin the fight against the fire more quickly.

On the way back to Yarnell, where their vehicles were parked, the crew was headed for a ranch deemed so safe that firefighters had called it “bombproof.”

Unlike other structures in Yarnell that officials would later deem indefensible -- because of how exposed the buildings were to overgrown chaparral -- Boulder Springs Ranch had fire-resistant construction and enough space to fight off a fire.

Yet even the so-called bombproof ranch would suffer its own scare as the inferno started to claim Yarnell.

“The owner of the Boulder Springs Ranch, on the town’s west edge, happens to go outside to check on her dog,” the report narrates.

“As she gets to the door, she realizes the fire has advanced significantly toward her house. She and her husband run outside, put all of their livestock into the barn, and then return to their house just as the fire sweeps over their property. The owners, their animals, and their property are unharmed thanks to fire-resistant construction and defensible space around their buildings.”

By this point, so much smoke had descended on Yarnell in the middle of the afternoon that motorists turned on headlights and security cameras switched to night vision, tricked into thinking daylight had suddenly ended. At least 100 buildings would eventually be destroyed as the wind-driven flames invaded the town.

It would take almost two hours for a helicopter to spot the ranch and, near it, the bodies of the 19 firefighters, to the surprise of rescuers who thought the men had taken a different, safer route out.

The downed crew had huddled together in a 24-by-30-foot area, some of them side by side, as the avalanche of flames, estimated to be 70 feet long and moving almost horizontally along the canyon where they lay, ate away at the foil of their emergency fire shelters.

The fire had raced to them so quickly that not all had time to hide under their shelters; the heat had become so intense that it melted helmets and gloves, even those of firefighters who’d properly set up their gear.

By the time rescuers arrived, there was nothing to be done.

The bombproof ranch -- their island of safety -- sat 600 yards away, perfectly safe.

ALSO:

No negligence in deaths of 19 Arizona firefighters, report says

Krokodil, more dangerous than heroin, possibly surfaces in Arizona

Prison: O.J. Simpson not caught stealing cookies, oatmeal or otherwise

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.