Firms oppose California bill to disclose policing of labor practices

California companies say they won’t deal with suppliers who use forced labor to dig out gems for jewelry or sew buttons on clothes. But they won’t support legislation that would force them to divulge what they’re doing to monitor their suppliers’ workforce practices.

A bill by Senate President Pro Tem Darrell Steinberg (D- Sacramento) would require retailers and manufacturers with annual revenue of at least $100 million to post on the Internet what they’re doing — or not doing — to ensure that no one in their supply chain violates human rights.

The idea is to give shoppers and investors who want to support companies taking anti-slavery stands an opportunity to spend their money in a socially conscious way, proponents such as British actress Julia Ormond have argued.

Many companies, such as Gap Inc. and Nike Inc., voluntarily police suppliers’ labor practices such as mining rare metals in Africa or sewing dresses in East Los Angeles, they said.

But major statewide business groups oppose any state mandate that could make them the target of government enforcement actions and resulting bad press.

“These are the kinds of issues that create great consternation for my companies, which spend a lot of time worrying about their image,” said Dorothy Rothrock, a vice president of the California Manufacturers and Technology Assn.

The bill would require companies to reveal publicly whether they hire outside experts to check suppliers’ labor practices, whether they conduct independent and unannounced audits of suppliers and whether suppliers certify that raw materials are processed in accordance with local and international labor and safety laws.

There’s nothing onerous about the bill, said Steinberg, noting that it would affect only about 3.2% of California businesses. “These requirements seem relatively simple and very doable,” he said.

What’s more, he said, “it’s good business to ensure that workers who make your products are treated with respect and dignity.”

The bill, SB 657, passed the state Assembly and is awaiting a final vote in the Senate this month.

“Business has a vital role to play in using their supply chains as the road map to tackling strategically and impactfully the worst forms of poverty on the planet,” Ormond testified at a recent legislative hearing. “Consumers need to know their level of engagement so they can make informed choices.”

More than 12 million people are subjected to forced labor worldwide, said Ormond, who appeared in the 2008 film “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” and founded the Alliance to Stop Slavery and End Trafficking.

But learning what companies might be doing specifically to combat widespread human rights violations is not easy, activists contend.

“It’s difficult for consumers to find out what’s going on. It’s not transparent,” said Lisette Arsuaga, communications director for the Coalition to Abolish Slavery and Trafficking. “This bill is a start to having a clear understanding of the entire supply chain.”

Getting that clear picture could be nearly impossible for many companies, said Marc Burgat, vice president of the California Chamber of Commerce.

Most California companies, he said, are being asked “to do things they are simply unable to do — to assure everything in the product chain down to raw materials is free from slave labor.”

Any retailer or manufacturer that states on its home page that it’s doing little or nothing to check on its suppliers could expect to get bad press, Burgat warned, while companies that fail to report at all could be hit with an injunction from the state attorney general’s office.

“There’s no defense in the eye of the public for being investigated by the AG for slavery and human trafficking in the 21st century,” he said.

Business groups are hoping to alter Steinberg’s bill substantially to make its provisions voluntary or at least to define more specifically which companies would be affected.

If that doesn’t work, they will seek a veto from Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. The governor, who met with Ormond on June 29 after she testified in favor of the bill, has not taken a public position on the proposal, said spokeswoman Rachel Arrezola.

However, Arrezola said, Schwarzenegger “has long been committed to eliminating the practice of human trafficking and providing protections for victims.” In previous years, he signed into law a number of bills that increase anti-slavery enforcement.

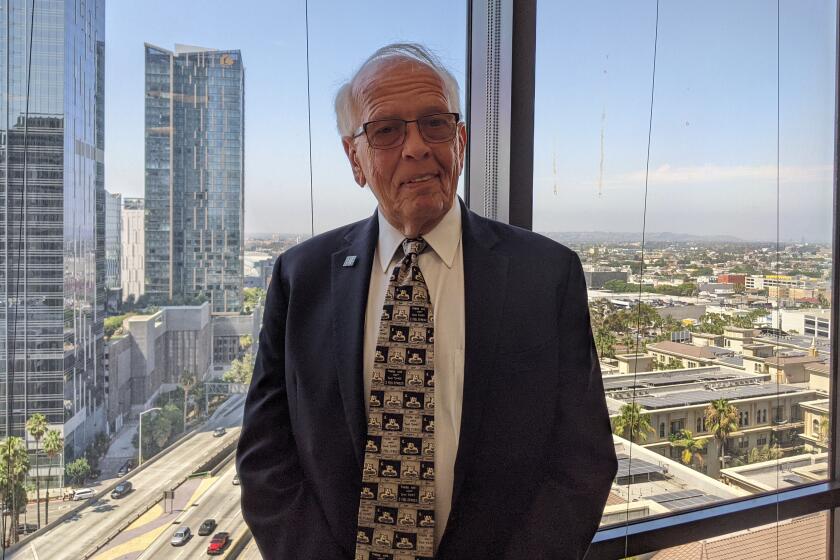

Businesses would be smart “to get ahead” of growing consumer interest in buying slavery-free products, even if it drives up costs, said Al Osborne, senior associate dean at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management. Such interest is similar to shoppers’ wanting to buy environmentally friendly goods and organic food.

Ideally, Osborne said, businesses should voluntarily tackle forced-labor issues and be subjected to government regulation only if the problem isn’t addressed.

“It seems to me that companies that large would know whether or not they have challenges in their supply chain,” Osborne said. “They’d be incented to try to correct them from a public relations point of view.”

marc.lifsher@latimes.com

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.