Annual retainer fee buys patients more time with their doctors

Frustrated with a changing healthcare system that has resulted in longer work days and less time with patients, a growing number of doctors in California and across the nation are turning to a new type of practice — concierge medicine.

The model is simple: Doctors charge their patients an annual fee and in turn, give them more time and attention.

Rising costs and shrinking insurance reimbursements have prompted doctors to search for innovative ways to keep their solo practices afloat. Concierge medicine, practiced by more than 5,000 physicians nationwide, provides them with extra income and allows them to limit their patient rolls.

Michael T. Duffy, a physician in Beverly Hills, recently made the decision to switch from traditional private practice to concierge medicine. He hopes to reduce his patient load from 2,000 to about 400.

“I was just spending more and more hours working and finding that the revenue was decreasing and my overhead was increasing,” he said. “I felt I needed to make a change.”

Concierge medicine started in the 1990s in Seattle and has steadily grown in popularity, according to physician organizations and a medical ethics journal. But critics say it fosters two-tiered medicine, where patients who cannot afford the extra fees are cut off from their doctors. And if too many physicians make the shift, experts say it could exacerbate the existing shortage of primary care doctors — especially when millions more Americans qualify for insurance in 2014 under national health reform.

The practices “raise ethical concerns that warrant careful attention, particularly if retainer practices become so widespread as to threaten access to care,” according to theAmerican Medical Assn.guidelines on concierge medicine, also known as retainer or personalized medicine. The guidelines also say that the physicians shouldn’t abandon their patients.

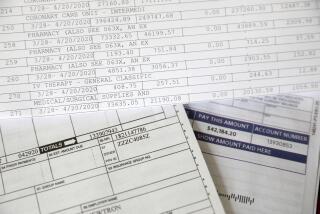

Matt Jacobson, a businessman who started SignatureMD in Marina del Rey in 2006, said doctors who sign on don’t want to practice “production line, seven-minute visit medicine.” Patients who pay an annual fee of from $1,500 to $2,500 receive a variety of perks, such as round-the-clock access to the doctor and on-time appointments for that day or the next. The fee may depend on where the doctor practices and the specialty.

Concierge doctors often provide a comprehensive physical and extra screenings, as well as helping coordinate their patients’ care with specialists or when they go to the hospital. Most doctors continue to take insurance, but others only take cash.

Everyone deserves to be healthy, but healthcare is a business, Jacobson said. Unless they pay for it, everyone doesn’t have the right to choose their provider, he said.

“Some people view going to a private school as the most important thing,” he said. “This is the same thing. Some people view healthcare as very important. They are going to cut their cable bill to see the exact doctor they want.”

One of Duffy’s patients, Sandra Collins, 50, said she was initially reluctant to pay the additional $1,800 since she already pays $380 each month in private insurance premiums. But in the end, Collins, a make-up artist, said she didn’t want to go to another doctor.

“I don’t want to lose Dr. Duffy,” she said.”If something does happen, I know he’s going to be there for me.”

Russell Douthit, 83, said he and his wife dipped into his savings so they could stay with Duffy. Douthit, who is on Medicare, said he wanted a doctor who would closely track his health and wouldn’t rush him through appointments.

“Medical care is certainly our No. 1 thing,” he said. “Things are starting to happen that happen to people my age. I am going to need some attention.”

Duffy said shaking up his practice after more than 20 years has not been easy. He said some of his patients have embraced it and some have questioned it, but everyone understands it. The patients who stay with him will have more direct access, an extensive physical exam, more screening and longer appointments. He said he planned to hire someone to look after the rest of his patients.

“I do not view it as any victory to have to tell them I can’t see them anymore,” he said. But he added, “Going broke is not the solution to serving more patients.”

Another SignatureMD doctor, Robert Saltman, in St. Louis, said he resisted switching for a long time but finally realized that he didn’t have a choice. “My wife said, ‘Your patients are going to live to a ripe old age and you are going to die early,’” he said.

He went from seeing between 20 and 25 patients a day to seeing between eight and 14, and he doubled the length of the appointments. Now, Saltman said he has the time to be proactive with patients and emphasize prevention and lifestyle changes. He hired a younger doctor to care for the primary care patients who chose not to pay the retainer.

Saltman said he didn’t become a concierge doctor to increase his income. “I did it to continue to do something I love without being resentful,” he said.

One of his patients, Mitch Waks, said he had several health issues, including high cholesterol and blood pressure. Nine months later, he said he was 60 pounds lighter and his cholesterol and blood pressure have dropped to normal, and he credits Saltman’s personalized attention for the improvement.

Waks said he can justify the ethical dilemmas of paying his doctor extra for personalized medicine even as so many lack basic healthcare. “Is it bad that I am able to buy a BMW rather than a Chevy?” he said. “I don’t think so.”

The American Academy of Family Physicians doesn’t consider concierge medicine the ideal model for primary care, said President Glen Stream. But Stream said he recognizes why physicians have made the switch.

“It is an adaptation to a dysfunctional healthcare environment,” he said. “We recognize people’s need to adapt, to be able to provide services to their patients. As long as they are providing good-quality care, then it is something we understand.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.