Serene Hilltop Marks Site of Landmark Disaster

The chirping of birds and the whoops of children frolicking in the grassy hollow give the hilltop a sense of serenity now.

It was different 40 years ago. There was a gurgling sound, a warning scream and finally a whooshing roar as death and destruction swept down a ridge into a Los Angeles neighborhood.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. Dec. 18, 2003 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Thursday December 18, 2003 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 1 inches; 57 words Type of Material: Correction

Baldwin Hills -- A Surroundings article in the California section on Dec. 11 about Baldwin Hills incorrectly said the discovery of oil there garnered Elias “Lucky” Baldwin his nickname. The discovery occurred after Baldwin’s death on land he had owned. But the oil strike came to enhance his reputation as a colorful Los Angeles speculator and pioneer.

The Baldwin Hills Dam collapsed with the fury of a thousand cloudbursts, sending a 50-foot wall of water down Cloverdale Avenue and slamming into homes and cars on Dec. 14, 1963.

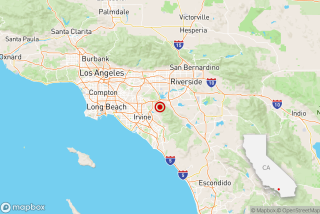

Five people were killed. Sixty-five hillside houses were ripped apart, and 210 homes and apartments were damaged. The flood swept northward in a V-shaped path roughly bounded by La Brea Avenue and Jefferson and La Cienega boulevards.

The earthen dam that created a 19-acre reservoir to supply drinking water for West Los Angeles residents ruptured at 3:38 p.m. As a pencil-thin crack widened to a 75-foot gash, 292 million gallons surged out.

It took 77 minutes for the lake to empty. But it took a generation for the neighborhood below to recover. And two decades passed before the Baldwin Hills ridge top was reborn.

The cascade caused an unexpected ripple effect that is still being felt in Los Angeles and beyond.

It foreshadowed the end of urban-area earthen dams as a major element of the Department of Water and Power’s water storage system. It prompted a tightening of Division of Safety of Dams control over reservoirs throughout the state.

The live telecast of the collapse from a KTLA-TV helicopter is considered the precursor to airborne news coverage that is now routine everywhere.

The dam break was Richard N. Levine’s big break, too.

Levine was a 17-year-old Dorsey High School photography student who was doing homework at his house two miles from the dam when he heard one of the KTLA reports by helicopter pilot Don Sides and cameraman Lou Wolf.

He grabbed his own camera, jumped into his 1948 Plymouth and hurried toward the dam. He parked in what he hoped would remain a dry spot behind the Baldwin Hills Theater. Then he hitched a ride on a firetruck up Punta Alta Drive and soon found himself standing atop the threatened dam.

Nearby, DWP workers were examining the crack in the sloping, paved inside wall of the reservoir. Suddenly a warning was shouted.

“Somebody yelled ‘There she goes!’ and men started scrambling back toward where I was. The dam didn’t go that quickly -- there was a kind of whirlpool at first and then pieces of it started disappearing,” Levine recalls.

The youngster captured a striking record of the dam failure, showing the progression of the collapse in a series of photos. Then he ran down the hill from the dam, documenting the wall of water crashing through homes on Cloverdale Avenue and Terraza Drive.

“Water was rolling and boiling like it was in a Colorado River gorge. Waves were washing away a row of homes. I was thinking these poor people are losing very nice houses. When I ran out of film I ran down the hill to my car. It was axle-deep in muddy water.”

Levine sold eight of his photos -- which were later reprinted worldwide -- to The Times for $200. He used the cash to buy a pair of lenses and an electronic flash for his Miranda T 35-millimeter camera. The incident launched a photojournalism career that included war coverage in Vietnam and newspaper work in the Los Angeles area.

Now 57, Levine turned to digital photo and computer work before relocating to Santa Fe, N.M. There he is a computer-support technician and fine-arts landscape photographer.

Back in Los Angeles last weekend, Levine revisited Baldwin Hills for the first time in years. “It was surreal. It’s changed -- the same fence I shot pictures through is still there. But the top is all grass and trees instead of asphalt and concrete,” he said.

The reservoir was never rebuilt. Instead, county Supervisor Kenneth Hahn proposed in 1968 that it be turned into a park. Fifteen years later, the empty lakebed was partially filled in and the Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area was created.

Many of those whose homes were destroyed never returned to Baldwin Hills. Some remained haunted by the experience -- and the thought that hundreds could have died if the dam had collapsed without warning.

Cheryl Merrill was 3 when the dam failed and her home was destroyed. Her family rebuilt within a year. But recently she has tried to learn who alerted her family and her neighbors in time to run for their lives.

“Though it was a disaster, some person enabled a lot of people to escape in time. That foresight saved my life, as well as a lot of other people. I just want to find out the name of the man or woman who spotted the crack in the dam,” said Merrill, a Web site designer in San Francisco.

The hero, according to a Times report from 1963, was “appropriately a man named Revere” -- Revere G. Wells, a caretaker at the reservoir.

At 11:15 a.m. the day of the collapse Wells heard a gurgling noise and sounded the alarm to his boss. Supervisor Pat Daugherty in turn summoned engineer Richard Hemborg. An hour later, Hemborg was authorized by DWP manager Samuel Nelson to ask Los Angeles Police Chief William H. Parker to evacuate the area beneath the dam. Between 1:30 and 2 p.m. an evacuation zone was mapped out and at 2:20 p.m. the first SigAlert aired.

Sixty motorcycle and patrol car officers were sent to knock on doors in the danger area. When the dam broke, 29 motorcycles were lost as police scrambled to housetops to escape the water. Eighteen residents trapped on rooftops and in debris were rescued by firefighters in helicopters.

Numerous hearings and investigations followed the collapse. Engineers argued over why the dam -- hailed as a $10-million state-of-the-art structure when it was built in 1951 -- failed. Many blamed an earthquake fault beneath the reservoir.

But federal geologists in 1976 concluded “exploitation of the Inglewood oil field” beneath Baldwin Hills caused land under the dam to sink.

Oil had been struck there in 1924 by land developer Elias J. Baldwin, garnering him the nickname “Lucky” Baldwin. In 1963, the lucky streak ended.

*

For a video of the Baldwin Hills Dam disaster see latimes.com/surroundings

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.