War Reporting an Issue in Suit Against ABC

If a reporter refuses to go to a war zone, can his employer fire him?

No, say a growing number of codes of practice for journalists worldwide, developed in response to the increasing danger of war reporting. The News Security Group, formed in 2000 to establish guidelines to protect journalists, says clearly that “assignments to war zones or hostile environments must be voluntary.” Networks such as CNN, ABC News, CBS News and NBC News have all agreed to follow the guidelines.

Mindful that 41 journalists have been killed in Iraq alone since 2003, most American news organizations also have voluntary war zone policies.

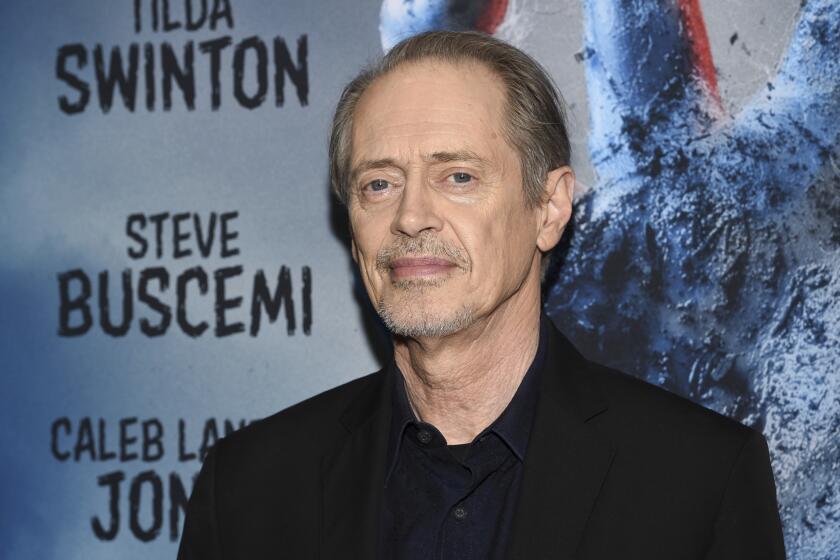

Yet Richard Gizbert, a London-based reporter for ABC News since 1993, believes that his contract with the network was terminated because he turned down assignments in Afghanistan and Iraq.

ABC executives asked Gizbert, who covered the fighting in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Chechnya in the 1990s, to go to Afghanistan in 2002. After he refused, they twice asked him to go to Iraq -- once during the buildup to the invasion in 2003, and a second time after the war had started.

Gizbert says he discovered that he was being fired at a meeting in June 2004 with Marcus Wilford, ABC’s London bureau chief.

“He told me: ‘We’ve decided to terminate you. ABC wants to replace you with a correspondent who will travel to war zones,’ ” Gizbert recalled. “I said, ‘You’re firing me because I won’t go to war zones?’ ‘No,’ he said, ‘we’re terminating you and replacing you with someone who will.’ And I said: ‘Isn’t that the same thing?’ ”

Wilford would not comment on Gizbert’s case for legal reasons. Nor would the news department’s head of communications, Jeffrey W. Schneider. But, he said the company’s policy was that “war zones are always voluntary assignments. We respect the personal decision of anybody who works for us regarding their desire to travel to a war zone.”

Nevertheless, Gizbert is suing ABC News for unfair dismissal at a British employment tribunal, seeking more than $4 million in damages.

He has called numerous network executives to testify, including ABC News President David Westin and Senior Vice President Paul Slavin. They will probably testify by video link from New York, Gizbert said, but Mimi Gurbst, vice president in charge of news assignments, is scheduled to travel to London to give her evidence to the June 14-16 hearing.

“ABC wanted her to testify by video link, but we fought that and won,” he said. “The employment tribunal has ruled that she must testify in person.”

Three years ago, Gizbert, like other seasoned war reporters who marry and have families, decided he had taken enough risks. At age 44, the father of two renegotiated his contract to exclude war reporting.

Gizbert gave up the perks foreign correspondents enjoy: lucrative housing and school-fee allowances and paid home leave. He accepted a more modest 100-day-a-year contract, earning a flat $1,000 per working day for baby-sitting the London bureau -- covering politics and European news -- while reporters were sent on war assignments.

The payoff, for him, was that he would no longer be asked to cover wars. “I’ve done my time on the front line,” he said. “There are very few lifers in news organizations. People have kids and stop hanging out in those areas.”

Still, he said it wasn’t long before the requests to don a flak jacket started coming again.

He said his no-war-zone contract, negotiated in July 2002, expired July 23, 2004, a month after his conversation with Wilford. He said he had offered to move back to the United States, or to go to war zones, after all, until a new job came up, but his offers were rejected. After the attempts to renegotiate failed, he said, he filed his suit Oct. 22.

A growing number of journalists are reluctant to make risky trips to Iraq, which the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists rates as one of the five most dangerous places in the world for reporters.

“I have reporters who’ll go to Afghanistan, or Darfur, but don’t want to go to Iraq,” said Loren Jenkins, a veteran war reporter and now a senior foreign editor at National Public Radio. “Iraq is probably the worst situation any of us have had to face in terms of danger.

“In Vietnam or Beirut, say, you knew where the lines were. If you were a journalist, you were seen as a neutral noncombatant and your immunity was respected. But in Iraq, that line is not only blurred -- it’s just not there. If you are American they go for you because you’re American. You’re fair game for kidnapping, killing, whatever.... Sooner or later you say, ‘My odds are bad. I don’t want more.’ ”

Finding volunteers was relatively easy in the enthusiastic first months of the Iraq coverage. But these days, editors have to try harder to persuade reporters to staff Iraq.

“We still have volunteers, but I would say it’s harder,” said Alan Philps, foreign editor of Britain’s Daily Telegraph newspaper. “If it continues to be as dangerous as this, I can imagine having difficulties in another 12 months -- especially if the story loses its bite and correspondents aren’t getting in the paper three or four times a week, like they are at present. The calculation anyone would make is, why take the risk?”

Ann Cooper, director of CPJ, said: “There’s been a change from the era of macho reporting, when it was not cool to appear frightened. Now there’s much greater sensitivity to safety issues.”

Managing an Iraq correspondent adds significantly to the workload and anxiety levels of an editor. Good editors are solicitous about making sure their team in the field is as safe as possible, checks in regularly several times a day by phone and doesn’t take unnecessary risks.

“Our approach is pretty basic -- no story is worth your life,” said Jenkins of NPR.

“We’d rather not have the story than have a dead correspondent.”

Although there is potential for conflicting interests, with the editors’ need to staff Baghdad and the fall-off in willing reporters, foreign editors are adamant that they put no pressure on their correspondents to travel to Iraq. “It’s totally voluntary,” Jenkins said. “We’re not going to pressure anyone who doesn’t want to go. You can’t put pressure on.”

Asked if he’d heard stories of reporters being fired for refusing, Jenkins said: “None that I know of. I can’t imagine any editor doing that -- and I’ve not heard stories in the major media of anyone pressuring anyone.”

Gizbert disagrees.

“Someone watching Diane Sawyer throw a live question to a correspondent in Baghdad should ask whether that correspondent really wants to be there,” he said. “There are always a few who are there to make their reputation, who are young and keen. But I know there are also people there against their better judgment, who, if they don’t go, are no longer secure in their work.”

The networks are “trying to cover an unending war with a shrinking resource base -- not even what it was 18 months ago -- because a lot of people who would go to the war before don’t want to go now and become the target of kidnappers,” he said.

“I think the greater pressure now is a product of diminished resources, of everybody cutting back with just the same intense competition in coverage.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.