Vidal Sassoon dies at 84; hair stylist revolutionized the field

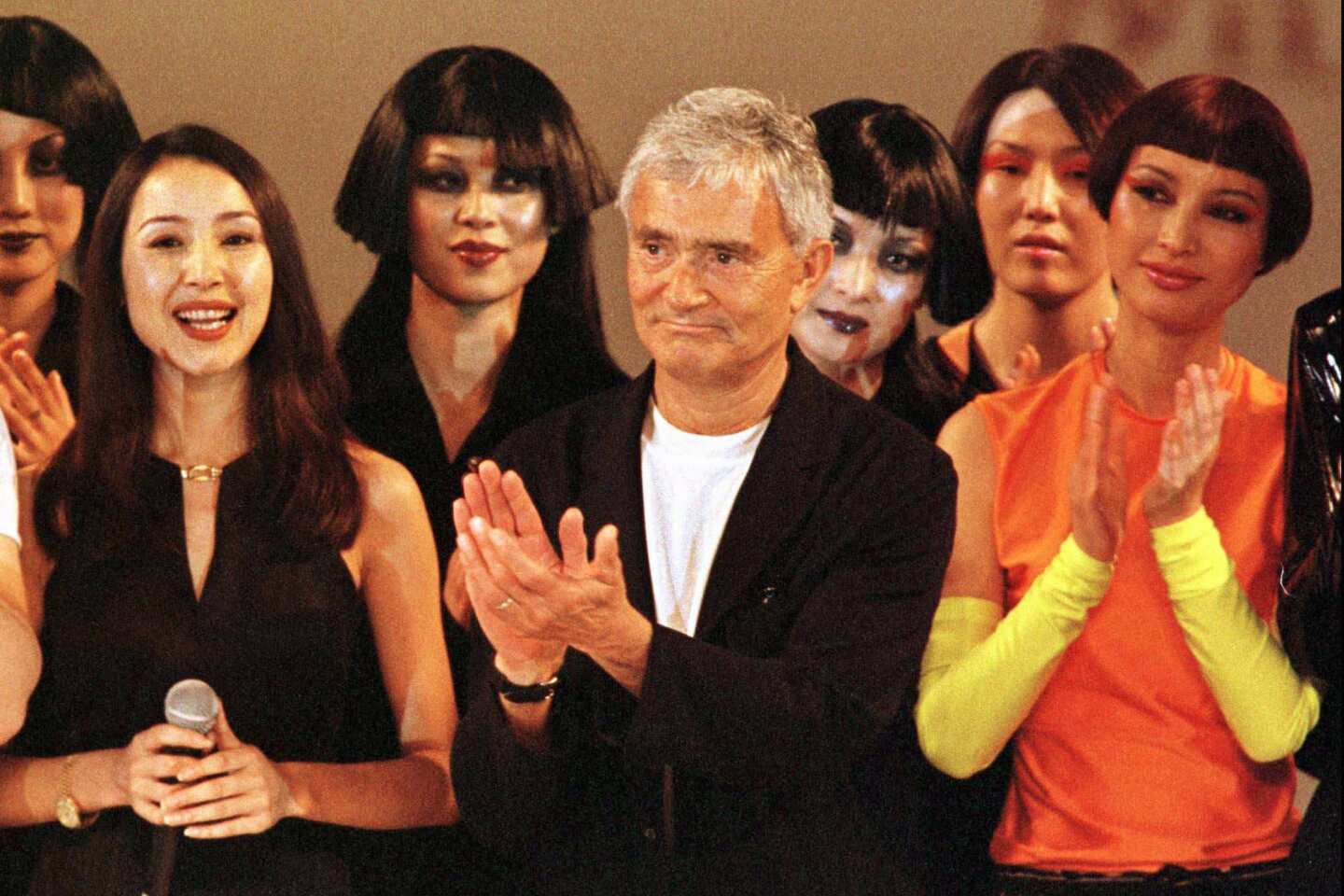

With one high-profile haircut on the Paramount Studios lot, Vidal Sassoon vaulted to fame in Hollywood.

Flown in from London, he trimmed the tresses of Mia Farrow for her role in the film “Rosemary’s Baby” — a $30 haircut that he calculated cost $5,000, including airfare.

The 1967 event was staged inside a makeshift “salon” in a boxing ring. The film’s director, Roman Polanski, looked on as Sassoon gave the actress a pixie cut that would be copied by women the world over.

As a celebrity hairstylist, Sassoon helped launch the age of the signature hair salon, complete with designer-label prices. He also revolutionized women’s hair styling with his signature sleek, geometric cuts. But his most enduring contribution was perhaps a simple one — he popularized the hand-held blow dryer.

Sassoon, who had leukemia, died Wednesday at his home on Mulholland Drive in Los Angeles, a family spokesman said. He was 84.

When Sassoon opened a hair salon in 1970 in Beverly Hills, the opening-night party also took on a theatrical flair when hundreds of celebrities, fashion and otherwise, “roamed up and down three levels in a merry melee,” The Times reported.

He moved his corporate headquarters to Los Angeles in 1974 and built a beauty business with global reach made up of hair-care products, signature salons and training academies that included one in Westwood.

When Sassoon used a blow dryer to create his innovative hairstyles, what had been a novelty item turned into a standard appliance in salons and homes. Hair rollers and helmet-style dryers became all but obsolete as a result.

“His designs have shaped the late 20th Century,” Richard Martin and Harold Korda, then curators at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, wrote in the introduction to the 1993 book “Vidal Sassoon, Fifty Years Ahead.” He brought “modernism to the medium of hair,” they wrote.

Television viewers across the country saw the man behind the name when he purred the memorable and satirized line in a 1976 commercial: “If you don’t look good, we don’t look good,” he said.

The London native said he never wanted to be a “crimper,” slang for a hairdresser. Yet he became the most influential crimper of his generation.

At 14, he had dropped out of school and, at his mother’s urging, took his first job in a hair salon.

“I kept thinking I would be spending my life up to my elbows in shampoo,” Sassoon wrote in his 1968 autobiography, “Sorry I Kept You Waiting, Madam.”

When he was about 20, he served as a volunteer soldier in Israel’s 1948 War of Independence and found that it gave him “a sense of dignity and the confidence that helped structure my future,” he later said.

After a decade laboring as a stylist in London, Sassoon finally captured fashion’s main stage in 1963 when he crafted an architectural haircut for fashion designer Mary Quant, then one of London’s bright young talents who is credited with inventing the miniskirt.

She wanted a new look for her, and her models, to wear in a fashion show. In sharp contrast to the reigning pouf of the day, he cut a blunt-edged bob that angled down toward her chin.

Fashion editors took note of the models’ haircuts, and Sassoon’s name quickly became associated with top fashion models, notably British cover girl Jean Shrimpton, and with young British pop musicians starting with the Beatles, whose blunt cut bangs, done at the Sassoon salon, launched a unisex hair trend.

He followed his “Mary Quant bob” with two other looks that confirmed his taste and style. The first was a “five point” cut that resembled a bowl with peaks at the nape of the neck and in front of the ears. The following year he introduced an “asymmetric bob,” cut longer on one side than the other.

To get the flat, shaped effect he wanted, he phased out the hair curlers and stationary dryers typical of the day. His portable blow dryer and a styling brush became his main tools, along with his scissors.

“To me hair dressing means shape. It’s very important that the foundations should be right,” he wrote in his autobiography.

In interviews, he said his low-maintenance hairstyles gave women greater freedom and independence, buzzwords for the social revolution breaking loose in Europe and the U.S.

“In the ‘60s, everyone let their hair down and I was there to cut it in very straight, geometric lines,” he later recalled.

His maverick marketing of his product was apparent soon after he opened his first salon on London’s Bond Street in 1954. He arranged an unusual publicity tour to demonstrate his techniques across Europe, including staging a show at the zoo in Stockholm.

Other leading designers, including Andre Courreges and Paco Rabanne in Paris and Rudi Gernreich in Los Angeles, asked him to create hairstyles to complement their geometric fashion designs. Magazine editors dotted their trend reports with photos of Sassoon’s latest looks.

After nearly a decade in his first shop, he moved in 1965 to a ground-floor location nearby. Sassoon was after a young, hip clientele, and he gave his salon the sleek black-and-white modern look that signaled the change.

A year later, Sassoon joined forces with Lanvin-Charles of the Ritz as the featured hairstylist at a salon on Madison Avenue in New York City. It was his launch in the United States.

He moved his corporate headquarters from London to Century City in 1974 and made his home in Beverly Hills for many years.

It was a long way from his beginnings in Shepherds Bush outside London.

He was born Jan. 17, 1928, to a carpet salesman, Vidal Sassoon, who abandoned his family. His mother, Betty, worked in a dress shop but could not support her sons, so 5-year-old Vidal and his younger brother, Ivor, were sent to an orphanage.

“Like most ghetto kids I knew it was important to be ‘somebody’ so I became a good soccer player, because excelling at a sport seemed to make you special,” he said in “Vidal Sassoon, Fifty Years Ahead.” Soccer turned him into a lifelong fitness buff.

His remarried mother retrieved her sons from the orphanage after six years, and Sassoon got on well with his stepfather, Nathan Goldberg.

During World War II, when the children of London were evacuated to the country, Sassoon and his brother lived with foster parents for about a year. Back home in London, Sassoon left school.

Trying to break into the beauty business, Sassoon interviewed at Cohen’s Beauty and Barber Shop. When shop owner Adolph Cohen said he charged apprentices a fee of 100 pounds, Sassoon tipped his hat and said “Thank you, sir” on his way out of the shop. Cohen liked his courteous manner and let Sassoon stay without paying tuition.

He soon discovered that his cockney accent was a handicap for a young man with higher aspirations. “You couldn’t get a job outside the East End with a Cockney voice like mine,” Sassoon later said. To correct it, he took elocution lessons and went to the theater to listen to the trained diction of actors.

To practice cutting hair, he went to London’s skid row once a week and gave free cuts to the homeless.

In post-World War II London, anti-Semitism flared. Sassoon, who was Jewish and whose mother was a devoted Zionist, became involved in an anti-Fascist group and attended Zionist meetings.

When Israel declared its War of Independence, Sassoon joined an international group of volunteers to fight in the war. He spent the year in Israel’s Negev desert, where his unit took heavy casualties. A scurvy epidemic added to their troubles. But the experience gave him a strong sense of his own identity.

“It was the year that gave me the most confidence about the future,” Sassoon told The Times in 1985. “I came home after a year and although my profession was only hairdressing, I knew I could change it.”

He remained an active supporter of Israel. In the early 1980s he co-founded the Vidal Sassoon Center for the Study of Anti-Semitism with professor Yehuda Bauer at Hebrew University in Jerusalem and regularly traveled there.

After his year in combat, he worked at a number of hair salons until he opened his first shop.

Through the 1960s and 1970s, Sassoon expanded his empire with salons in European and U.S. cities. He also launched product lines in England and the U.S.

He wrote a book, “A Year of Beauty and Health,” with his then-wife, actress Beverly Adams, in 1975. Combining his passion for health and fitness with his knowledge of the beauty business, he broke new ground. The book remained a No. 1 bestseller for months.

After years of 60-hour workweeks, Sassoon said he was ready for a change. He sold his European salons and teaching academies to several of his colleagues in 1979, and the U.S. salons and schools in 1983.

When he sold his hair-care product line to Richardson-Vicks in 1983, his company’s annual revenues were a reported $110 million.

Procter & Gamble purchased the business in 1985, and Sassoon remained a consultant and spokesman until 2004. He had sued the company for failing to promote the product line to his standards, and the suit was settled out of court.

His first marriage, to a receptionist at his London salon, ended in divorce.

With his second wife, Adams, whom he married in 1967, he had four children, Catya, Elan, Eden and David. After the couple divorced in 1980, he was briefly married to Jeanette Hartford Davis. His daughter Catya died of a drug overdose in 2002.

Sassoon is survived by his wife of 20 years, Ronnie, three children and seven grandchildren.

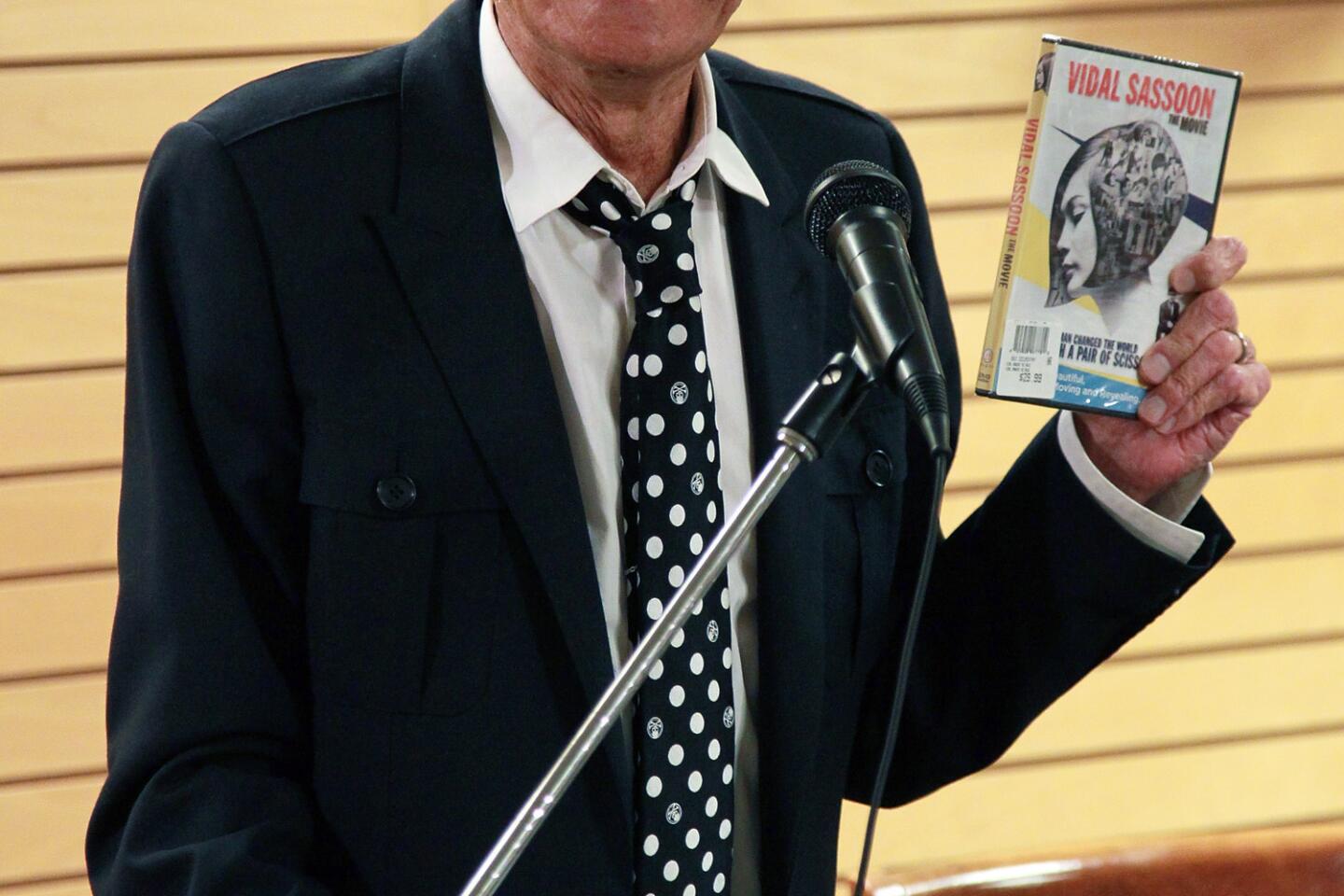

In the 2011 documentary “Vidal Sassoon: The Movie,” the stylist said: When “the doubters tell you it can’t be done, nonsense. If you can get to the root of who you are, and make something happen from it ... you are going to surprise yourself.”

Rourke is a former Times staff writer.

Times staff writer Valerie J. Nelson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.