Another route to same-sex marriage: Congress

Monday marks the 42nd anniversary of the 26th Amendment to the Constitution, which says: “The right of citizens of the United States, who are eighteen years of age or older, to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of age.” As President Obama noted on its 40th anniversary, “once proposed in Congress in 1971, the 26th Amendment was ratified in the shortest time span of any constitutional amendment in American history.”

But he didn’t explain why approval was so fast. The explanation is interesting in its own terms but also suggests a way that, if it is so inclined, Congress might accelerate the legalization of same-sex marriage.

It was actually in 1970 that Congress first tried to lower the voting age to 18 in state and federal elections alike as part of an extension of the Voting Rights Act. But in Oregon vs. Mitchell, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress had the power to lower the voting age only in federal elections.

That decision, handed down on Dec. 21, 1970, confronted states that wanted to retain a 21-year-old voting age for state elections with an administrative nightmare. They would have to keep two sets of registration records, one for state elections, another for federal elections. An unwillingness to engage in such double bookkeeping played a significant part in the swift ratification of the 26th Amendment.

Last week, the Supreme Court struck down a portion of the Defense of Marriage Act that defined marriage for federal purposes as the union of one man and one woman. Henceforth same-same couples married under state law will be entitled to federal benefits provided to married couples, though it is unclear how that will apply to couples married in a state that allows gay marriage who then move to a state that doesn’t.

As a result of the ruling, Congress may not refuse to treat a couple as married if their home state considers them married. But can Congress go in the other direction and provide tax, immigration and Social Security benefits to committed same-sex couples in states that don’t recognize same-sex marriage?

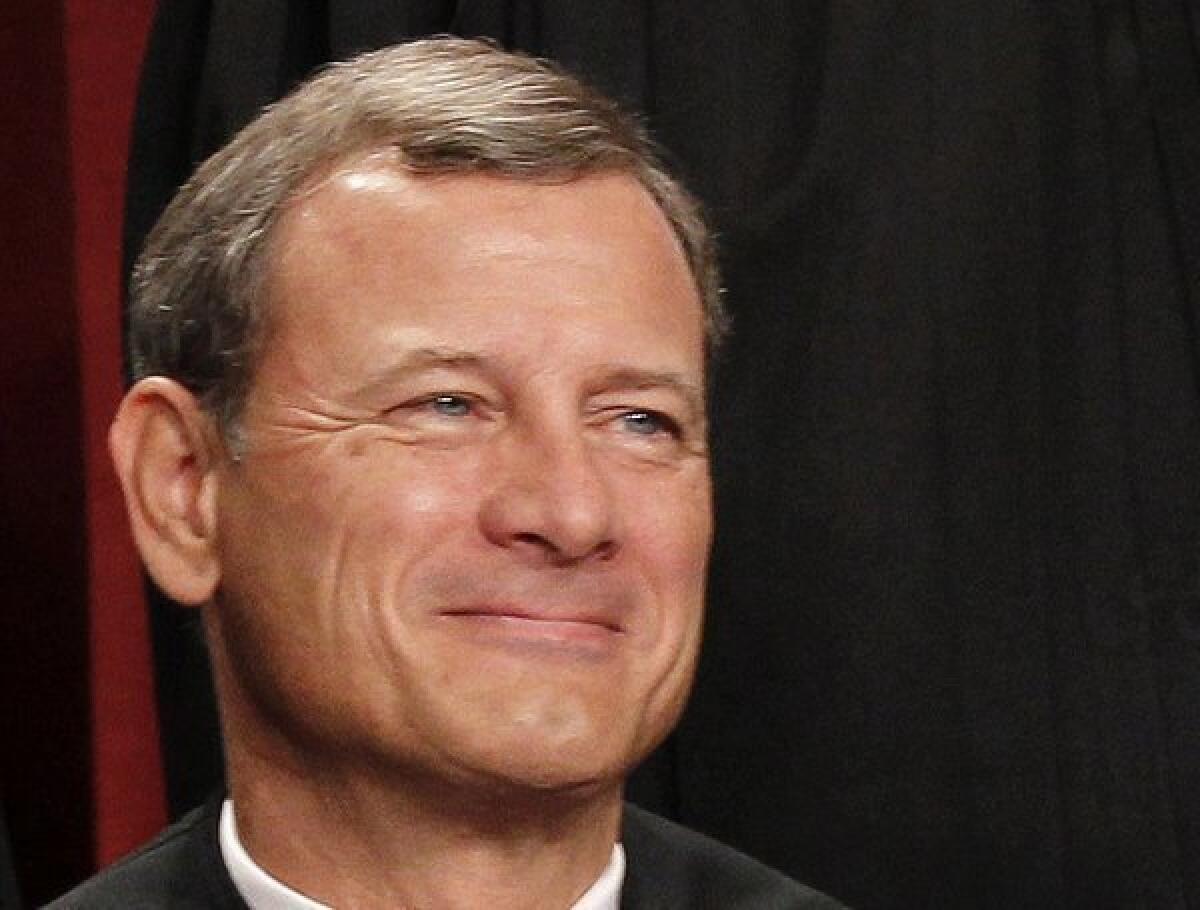

It may seem like a far-fetched idea, but it surfaced in oral arguments in the DOMA case. Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. asked Solicitor General Donald Verrilli Jr. if the Obama administration believed Congress could “pass a new law today that says, ‘We will give federal benefits. When we say marriage in federal law, we mean committed same-sex couples as well, and that could apply across the board.’” After some fencing, Verrilli essentially agreed that Congress could do that without creating a “federalism problem.”

Flash forward to last week and Justice Anthony M. Kennedy’s majority opinion striking down Section 3 of DOMA. Although Kennedy discussed the fact that states traditionally have been responsible for defining marriage, he didn’t ground the decision in states’ rights, as many court watchers had expected. Nothing in Kennedy’s opinion prevents Congress from doing what Roberts hypothesized: adopting a federal definition of marriage that would benefit same-sex couples even in states that don’t allow gay marriage.

That’s not going to happen tomorrow. It’s not even clear that there are enough votes in Congress to repeal a section of DOMA not at issue in last week’s decision: a provision allowing states to refuse to recognize same-sex unions from other states. But Congress is more receptive to changes in public attitudes about gays than some state legislatures are.

If Congress did create a sort of federal “marriage,” you would have a situation not unlike the one created by the Supreme Court in Oregon vs. Mitchell. A couple in, say, Texas, could be married for federal purposes but not for state purposes. The existence of dual definitions could provide some additional pressure on states to simplify matters by allowing same-sex marriage.

It might even, at some point, lead to a constitutional amendment mandating the acceptance of same-sex marriage by all of the states -- assuming that the Supreme Court hadn’t by then allowed what Justice Antonin Scalia called “the other shoe” to drop by striking down state laws against same-sex marriage.

ALSO:

Photo gallery: Ted Rall cartoons

An African epidemic of homophobia

Seize the mortgages, save the neighborhood

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.