Salmon are a sign of hope in a long-dry stretch of the San Joaquin

Agriculture and the Friant Dam, built in the 1940s, dried up a 60-mile stretch of the river. After a long, tortuous effort, a chinook spawns 10 miles downstream from the dam.

- Share via

Rene Henery, front, and Matt Bigelow spot a wild spawning chinook salmon in an upper portion of the San Joaquin River. (Bethany Mollenkof/Los Angeles Times) More photos

About 10 miles downstream from Friant Dam, two men gently guided their drift boat toward a spot where the riverbed gravel looked as if it had been swept clean.

There, in about a foot of water, they spied something that had vanished from the San Joaquin River more than 60 years ago: a spawning chinook salmon.

"How sweet," said Matt Bigelow, an environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. "I put in a lot of work to get to this point."

It was a small victory in a tortuous effort: to revive one of California's most abused rivers by restoring a portion of its long-lost water and salmon runs.

The San Joaquin's spring-run chinook once numbered in the hundreds of thousands. The salmon were so plentiful that farmers fed them to hogs. Settlers were kept awake at night by splashing fish as they struggled upstream to their spawning grounds.

The run dwindled as San Joaquin Valley agriculture sucked more and more water from the river system and hydropower dams blocked salmon from upstream passage. Then, in the 1940s, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation erected Friant Dam as part of the Central Valley Project, a massive irrigation system.

Most of the upper river flow was sent into two giant canals that fed irrigation ditches up and down the east side of the San Joaquin Valley. Sixty miles of the San Joaquin — the state's second-biggest river — died, its bed turning to a ribbon of dry sand.

The spring-run chinook disappeared. Hatchery releases sustained a small population of fall-run chinook that spawn in the San Joaquin's major tributaries.

In the late 1980s, environmentalists went to court to get back some of the San Joaquin's water — and its salmon. Their legal arguments focused on an old provision of the state Fish and Game Code that required dam owners to release enough water downstream to sustain healthy fish populations.

Charles Hueth, right, and Shaun Root, center, arrange a net used to trap chinook salmon that will then be released in an upper portion of the river as part of a restoration program. (Bethany Mollenkof/Los Angeles Times) More photos

After a nearly two-decade fight, environmental groups reached a settlement with the federal government and farmers supplied by the Friant operation. The 2006 pact called for irrigators to give up some of their supplies to restore year-round flows, and with them, part of the river's historic salmon runs.

But no one thought that reviving a river as degraded as the San Joaquin would be a matter only of adding water and fish and stirring.

Stretches of the old riverbed were choked with shrubs and trees. In some areas, the channel was hemmed in by flood levees. Farmers accustomed to a half-dead river had for decades grown crops in the old flood plain. When the first test flows were released down the dry riverbed a few years ago, water seeped beneath adjacent fields and damaged crops.

Restoration isn't like a light switch, where you flick it on."— Monty Schmitt.

The problems have pushed back by years the date when salmon will be able to swim all the way upriver to spawning grounds below Friant Dam.

"Restoration isn't like a light switch, where you flick it on and flows are flowing and fish are coming back and birds are flying overhead and people are picnicking by the riverside," said Monty Schmitt of the Natural Resources Defense Council, which led the restoration fight. "It is not something that happens all at once."

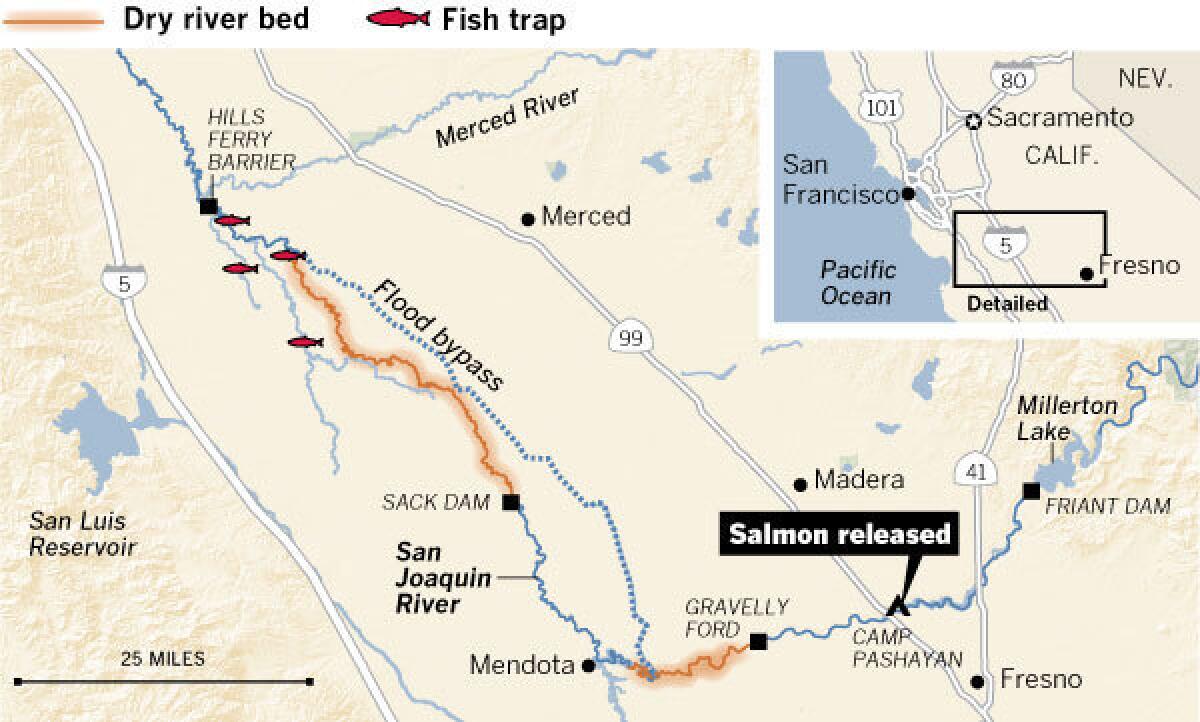

The salmon that Bigelow and Rene Henery of Trout Unlimited saw didn't get within 10 miles of the dam on its own. It was one of 104 fall-run chinook trapped over a period of weeks late last year and hauled in tank trucks down California 99 — around dry riverbed not yet restored — for release in the upper river at Camp Pashayan on the outskirts of Fresno.

Biologists wanted to know what the salmon would do in a part of the river inaccessible to them since Harry Truman was in the White House. Would they find suitable places to spawn, or swim around in futility?

On a gray day in early December, the two scientists were scanning the San Joaquin for answers.

When they spotted the lone chinook lingering in shallow water, they turned on a portable receiver to see if they could pick up a signal from one of the acoustic tags that had been inserted in some of the trapped fish.

The receiver started clicking. The number 7379 popped up on the instrument screen. A check of the trapping log the next day revealed the fish was a 3-foot-long female, caught in mid-November.

Now she was guarding the gravel bed where she had laid several thousand eggs and covered them with swishes of her tail, leaving behind signs of her nest, or redd, as salmon nests are called.

Studying her, the men could see that she was in bad shape. Her fins were deteriorating. Fungus was growing on her. Soon she would die, her biological role fulfilled.

No. 7379 wasn't the only female to find a gravel bed to her liking. Biologists counted 11 redds upstream of the release point.

Charles Hueth releases a salmon into the San Joaquin River at Camp Pashayan as part of a program to restore flows to dry stretches of the river and revive some of its historic chinook salmon runs. (Bethany Mollenkof/Los Angeles Times) More photos

Their presence proved that after more than a half-century absence, chinook would spawn in the wild in the upper San Joaquin.

But because water is still not flowing down the river's longest dry stretch, the hatching salmon have nowhere to go. The juveniles will hang out in the upper river until they become a meal for other fish.

"The system is not ready," said Cannon Michael, vice president of an agricultural company that farms 11,000 acres near the river. "You get some photo ops by trapping fish."

He and other farmers who are not parties to the settlement have nonetheless been drawn into the program because their agricultural operations lie along the 153-mile length of the project, which extends upstream to Friant Dam from the confluence of the San Joaquin and the Merced rivers.

They fret that there won't be enough government funding to fully implement all the elements of the program, which is likely to cost more than $1 billion. They worry that if spring-run chinook — protected under the federal Endangered Species Act — are reintroduced and don't survive, they will be blamed. And they don't want to lose cropland to the project.

"I don't think it's realistic. It's hard to re-create that," Jim Nickel said of the settlement goals. Like Michael, Nickel is a direct descendant of Henry Miller, who with Charles Lux built a cattle empire along the San Joaquin in the 1800s.

Nickel's family owns 8,000 acres, some of it along a portion of the river, below Sack Dam, that has been dry since the 1950s. In 2009, the first year the restoration program released test flows down that stretch, he was driving past a field of tomatoes with a farm manager.

"I'm sure having trouble getting those tomatoes to grow," the manager told him. They saw water in a field drain, even though the crop hadn't been recently irrigated. When they tested soil samples, they found salts.

Sources: San Joaquin River Restoration Program, ESRI, TeleAtlas. Graphics reporting by Bettina Boxall. (Lorena Iniguez Elebee / Los Angeles Times)

Nickel concluded that water was seeping beneath his fields from the newly wet riverbed, elevating the area's already high water table and pushing harmful salts into the crops' root zone. He installed a $250,000 interceptor drain to collect the seepage and filed a claim with the project, which reimbursed him and paid damages.

Nickel's problem was solved, but it was evidence of a troublesome issue that has stalled the release of flows down miles of riverbed. The narrowness of the old channel is another obstacle.

As the San Joaquin flowed across the Central Valley, it historically divided into a braid of smaller channels during flood years. In some places, what remains is too overgrown and small to accommodate the full volume of flows called for under the settlement.

In response, the project has installed more than 150 groundwater monitoring wells near the river. There are plans for more interceptor drains. And the program hopes to purchase easements — or even land — from farmers who own property next to the problem stretches.

"We're doing seepage projects, building levees, water control infrastructure," said Ali Forsythe, who is overseeing the program for the reclamation bureau. "It definitely goes beyond what I think a lot of people typically think of as a river restoration project."

It's her job to get the program past its many hurdles and balance the conflicting interests of landowners and environmentalists. "It's difficult," she said. "Sometimes it's emotionally taxing."

Still, Forsythe is confident the river one day will have enough water to ferry thousands of spring-run chinook upstream all the way to Friant Dam in an ancient rite of birth and death. "It will just take more time and more work and more money than originally anticipated."

PHOTOS: Trying to revive spring-run chinook salmon

Deaths of endangered fish curtail water exports