Editorial: Police use-of-force standards in California are inching upward

Modified to attract crucial votes in the state Legislature, a landmark bill to change how police use deadly force in California is moving forward without the support of what were once its most ardent backers, and without objection from its formerly most virulent opponents. Assembly Bill 392 advanced on the power of activism but is now a product of compromise. So is it still worthwhile?

Most definitely.

The bill still makes clear that police may shoot or use other deadly force only when necessary to prevent death or serious bodily injury to the officer or others. It cleared the Assembly earlier this week and now proceeds to the Senate.

The operative word is “necessary.” Under current law and court decisions, officers may use deadly force whenever doing so is “reasonable” under the circumstances.

The new California standard will inevitably recast the definition of “reasonable” use of force by police in the rest of the country.

It’s that switch from “reasonable” to “necessary” that was so controversial, and it remains, to those not steeped in the legalisms of police force, so confounding.

Assemblywoman Shirley Weber (D-San Diego) and Assemblyman Kevin McCarty (D-Sacramento), the bill’s coauthors, were motivated in part by last year’s shooting death of Stephon Clark at the hands of Sacramento police officers, who fired in the apparent belief that Clark was holding or perhaps even firing a handgun. The object in Clark’s hand turned out to be a cellphone.

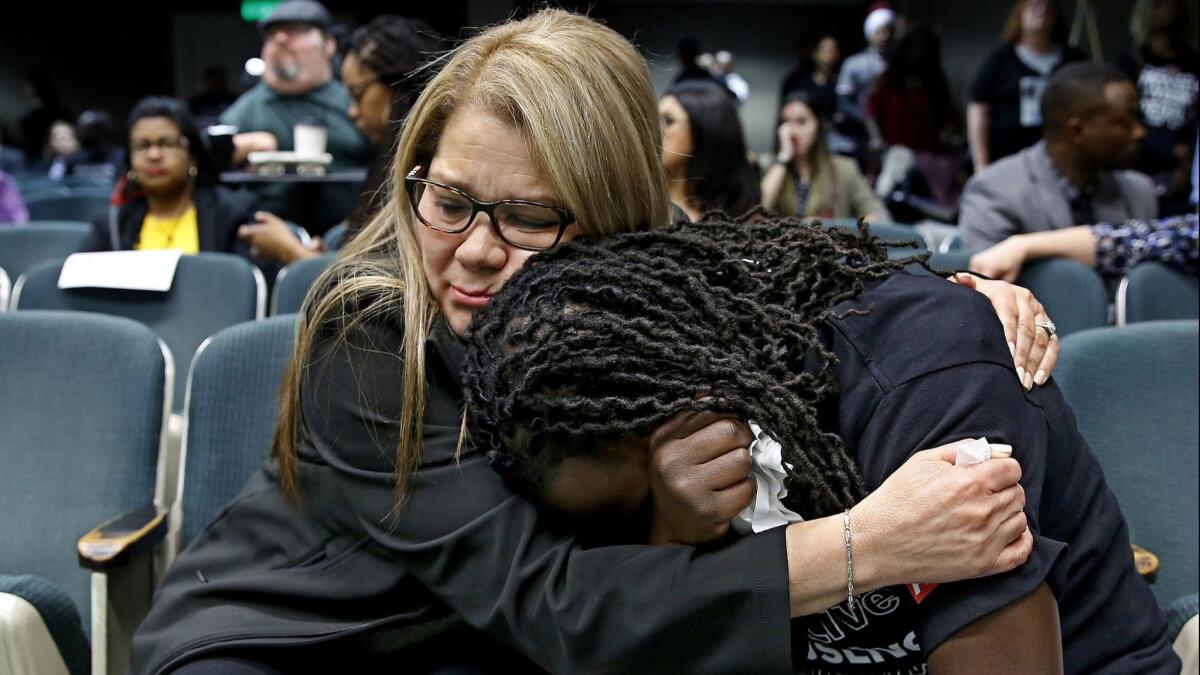

In a larger sense, though, the bill arose from a continuing series of fatal police shootings of unarmed African American men in and outside of California, such as Michael Brown Jr. in Ferguson, Mo., and Ezell Ford in Los Angeles in 2014 — and numerous others, whose deaths drew attention to police tactics and racial injustice.

Certainly there must be a way to prevent officers from needlessly killing people who pose no threat.

But the 1989 U.S. Supreme Court opinion in Graham vs. Connor appeared to set a ceiling on officer accountability by establishing the “objectively reasonable standard.” Under the 4th Amendment, the court held, “the ‘reasonableness’ of a particular use of force must be judged from the perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene, rather than with the 20/20 vision of hindsight.”

That means in essence that the nationwide law enforcement community determines for itself what is or is not a justified police shooting. That standard will necessarily rise over the years, as new tactics and training to reduce unnecessary force are adopted by forward-looking police agencies around the country, in effect redefining what action is “reasonable,” but that process of raising standards is achingly slow.

The California bill imposes a tougher standard — “necessary” instead of “reasonable.” Activists protesting the Clark shooting argued that the “necessary” standard would have allowed the officers to be held criminally liable for their actions. Police claimed that it would punish officers for split-second life-and-death decisions, and consequently endanger themselves and the public.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute »

Both sides were off-base. Any prosecutor or court would still have been required to consider whether it was reasonable for an officer to suspect that the phone in Clark’s hand might have been a weapon and that he was about to fire it.

But police dropped their opposition when AB 392 dropped its definitions of “necessary.” The bill now implicitly — but no longer explicitly — requires officers to exhaust all reasonable non-deadly alternatives before shooting. After all, isn’t that what “necessary” means? Perhaps — but that will now be up to courts to decide, if and when a fatal police shooting becomes the subject of a lawsuit or a criminal prosecution.

In the meantime, though, if the bill proceeds through the Senate and is signed into law, police agencies in California will be on notice of the new standard. Unless they are inordinately foolish, they will try to ensure that officers don’t shoot as a first resort by updating their training, as the Los Angeles Police Department already has done, and their internal disciplinary systems. The standards for police use of deadly force in California will rise — perhaps more slowly than they would have before the amendment that eliminated the definition of “necessary,” but still a bit faster than they would without the bill at all. And the new California standard will inevitably recast the definition of “reasonable” use of force by police in the rest of the country.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.