Community profiling’s long, sad history

As a Los Angeles County resident, a scholar and a Jew with a good memory, I was shocked and horrified to read of the Los Angeles Police Department’s antiterrorism bureau program to map Muslim communities. The debate over security versus individual rights that was popularized in the wake of the USA Patriot Act and invoked in this case is, in my view, the wrong debate. Targeting identity communities to protect society from those minority subgroups that seek to do harm as opposed to creating strategies to address criminal behavior is both morally repugnant and strategically misinformed.

Historically, mapping communities has been a precursor to actions against those communities. Why map if you aren’t going to try to act on the data collected? How is this method of protecting city residents different from, say, identification of Jewish areas that ultimately led to the oppression of the “Pale of Settlement”? The foundation for that action was Russia’s desire to protect its middle class. Deputy Chief Michael P. Downing’s argument that the Muslim mapping program would protect Muslims is even more offensive. How is this rationale different from the British justifying the occupation of Palestine in the early 20th century by claiming they were protecting the Jewish population?

Even the effort to identify radicalism within the Muslim community through mapping is subject to the vicissitudes of defining a “radical.” Puritan radicals in 17th century New England were rounded up, held as enemy aliens and restricted to defined zones, suspected of holding views that undermined liberal ideals. I would think that Downing would join the majority of Americans today who find the above cases to have been morally reprehensible mistakes. Why can’t we look at Muslim mapping with the benefit of hindsight?

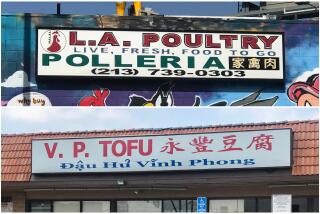

Strategically, we should have learned from recent U.S. policy failures that followed the targeting of identity groups in other countries, but I will eschew that political maelstrom. Clearly, all three cases of identity mapping above led to increased, not decreased, threats to the population; I am challenged to find any case that hasn’t. If we do want to try again to protect the population through identity-group profiling, then maybe we need to be honest about it. Why don’t we map African American communities? African Americans are convicted of crimes more often than white Americans. Why don’t we map Hispanic communities? Hispanics are convicted of crimes more often than white Americans as well. Wouldn’t identity-group profiling protect the population in these cases? After all, in 2001, according to the U.S. Statistical Abstract, there were 16,037 homicides in the U.S. more than five times the number killed on 9/11. I am confident that the vibrant public discourse spares me from having to answer those questions.

Perhaps ironically, one of the most articulate positions on both the moral and strategic problem with identity mapping has been made by the Bush administration. In a speech before Congress, President Bush stated that racial profiling “is wrong and we will end it in America ... stopping the abuses of a few, we will add to the public confidence our police officers earn and deserve.” The U.S. Department of Justice banned racial profiling, calling it unconstitutional. Under this definition, former Atty. Gen. John Ashcroft followed in February 2002, saying that using race “as a proxy for potential criminal behavior is unconstitutional, and it undermines law enforcement by undermining the confidence that people can have in law enforcement.” I guess the LAPD missed the memo.

Richard R. Marcus is assistant professor of international studies at CSU Long Beach, where he teaches, conducts research and publishes on community perceptions of macro-political change in Madagascar, Kenya, Israel and the United States.

Send us your thoughts at opinionla@latimes.com.More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.